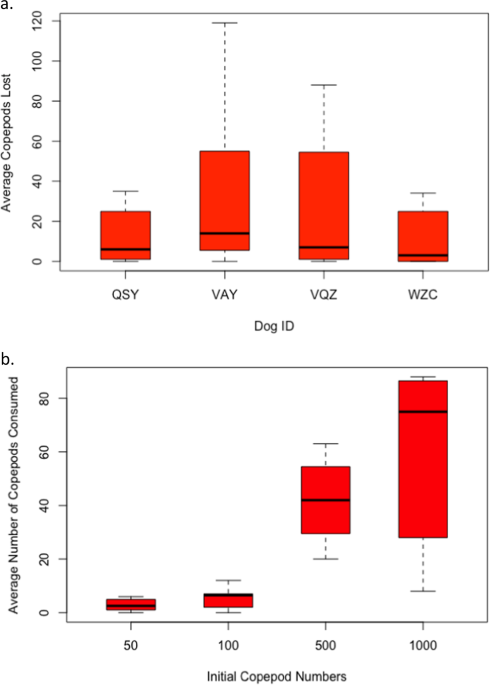

Our data indicate that under experimental conditions, dogs may ingest copepods during a drinking event. Thus, it is theoretically possible that enough infected copepods could be ingested to result in dog infections if the copepod infection rate was high enough. We also found that higher densities of copepods led to higher ingestion rates. In Chad, copepod density varies seasonally and between water-bodies. A recent survey found that the average annual number of copepods in four ponds in Chad was 100–200 copepods/L with periodic and short-term spikes of 400–700 copepods/L, primarily in the summer months (T. Moundai, unpublished data); however, additional variation may be present in other regions of Chad. Our highest density tested (1000 [500 copepods/L]) represents the highest naturally observed densities in Chad, while the lower and middle doses (100 [50/L] and 500 [250/L]) represent more frequently detected densities. If numbers of copepods ingested under natural conditions is similar to our experimental data, numerous drinking events from contaminated water bodies may be necessary for Dracunculus transmission to occur. It is important to note the prevalence of infected copepods in a contaminated pond is poorly understood but is presumed to be relatively low based on past studies (range of 0.5–33.3%, average of 5.2%)15,16,17. Also, because both a female and male worm are required to complete the life cycle, and copepods infected with more than one Dracunculus L3 are likely to die18, multiple infected copepods must be ingested. Although it is theoretically possible to have a single male and single female larvae mature, numerous experimental studies have shown that many ingested larvae fail to mature in definitive hosts; thus multiple infected copepods likely have to be ingested4,15. At copepod densities of 50 [25/L] and 100 [50/L], 3–7 copepods were consumed on average (Fig. 1b); thus the likelihood of a dog ingesting multiple infected copepods during the two to three week time period in which the copepods are infected with mature L3’s, and thus infections to a definitive host may be low. However, it cannot be ruled out or minimized, especially within the context of eradication.

Other considerations must be addressed during future studies, ideally under field conditions. Our dogs were maintained indoors under climate-controlled conditions (21 °C), whereas there are more extreme temperatures (40 °C to 43 °C) during the peak transmission season in Chad. To partially account for this, water was withheld from dogs for 12 hrs (maximum allowed). Also, our copepods were collected from Georgia, USA which may behave differently than Chadian copepods. Relatively small glass dishes were used in this study; however, wild copepods likely have more opportunities to flee from dogs within larger water volumes. Finally, under natural conditions, copepods may flee into substrate of water-bodies, which is especially known to occur during daylight hours19. Another important consideration is that dogs in Chad will often wade and lie in water-bodies leading to disruption of copepods, which could influence the likelihood of ingestion. It is possible that this disruption could decrease risk of ingestion as copepods flee the disturbance. This is assuming that the behavior of infected copepods is similar to uninfected copepods. One study by Onabamiro (1954) found that infected copepods were more sluggish than uninfected copepods; however, a large number of parasites were provided to copepods so many likely had multiple larvae which could have impacted their behavior more than what typically occurs in nature (copepods infected with a single larva)16,20.

In conclusion, despite our small sample size, our data indicate that dogs can ingest relatively few copepods while drinking, but there are still many factors to investigate to determine the primary transmission route(s) of D. medinensis in the remaining GWD-endemic countries. Other possibilities include ingestion of amphibian paratenic hosts or fish transport hosts2,4,5,6,15. Currently, there are many interventions in place to minimize transmission risk including: tethering of infected dogs, treatment of potentially contaminated water bodies with Abate®, and the burning or burial of fish entrails, but dog infections continue to occur suggesting that improved adherence to interventions or new interventions are necessary to interrupt transmission. Continued evaluation of transmission routes, in the field and theoretically, may help refine or develop interventions.

Disclaimers. The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Source: Ecology - nature.com