The Central Bureau of Statistics of DPRK with support from UNICEF integrated water quality testing (and other service indicators) for the first time allowing for the assessment of safely managed drinking water services. Currently, based on the latest census figures (population 24,052,231) and 2017 DPRK MICS results, it is estimated that around 19 million people utilise sources of water free from faecal contamination and that around 15 million people have access to safely managed drinking water services. Whereas universal access to drinking water is an ambitious goal set by SDG target 6.1, use of the new “safely managed drinking water service” indicator addressed many of the limitations of MDG monitoring by addressing water quality, accessibility, and availability.

Only a limited comparison to previous MICS (19986, 20007, and 20098) is possible as the survey has changed in its different editions regarding water-related questions. Notably, no previous survey had a dedicated water quality module as was done in 2017. The level of reported access to an improved water source in previous (MDG era) surveys was of 99.8% (1998), 100% (2000), and 99.9% (2009). A slight decrease in the 2017 survey was observed (93.7%); this may be attributed to a better and clearer set of definitions regarding improved water sources. At the same time, there is a noticeable drop in the use of piped water into own dwelling, into yard/plot and public taps between previous surveys, census and 2017 DPRK MICS. For instance, access to piped water was 89% during 2009 DPRK MICS and 59% in 2017 DPRK MICS. These differences may be due to changes in the methodology, training of field teams, and/or verification of water sources used by households afforded by the water quality module.

Despite these differences between surveys, access to improved sources is relatively high in comparison to household survey-based studies on other low and lower-middle-income countries12. Additionally, the level of access to improved sources in the DPRK was also comparable to upper-middle and high-income neighbouring countries regarding JMP estimates13; 96.7% for China, 97.0% for the Russian Federation, and 99.6% for the Republic of Korea.

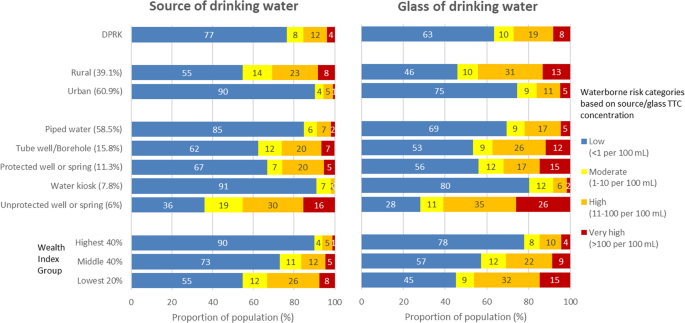

The inclusion of testing for faecal contamination (at source and household) and a set of questions on drinking water availability allowed for an improved understanding of where efforts should be focused to achieve safely managed drinking water services. This is of particular importance in countries such as DPRK where most households use improved drinking water sources. As shown in Fig. 1, water quality often deteriorated between the water source and a glass of drinking water, a pattern observed in urban and rural areas and across provinces, WIGs and different types of water source. This situation is compounded with the fact that less than a fifth of households reported using an appropriate method of water treatment, of which boiling was the most frequently reported method.

Increasing accessibility and quality of drinking water are the key priorities for the DPRK to achieve universal access to safely managed drinking water sources and progress towards SDG target 6.1, with rural areas requiring the greatest improvements. Access to safe drinking water on premises will improve the quality of life especially for women who disproportionately shoulder the burden of fetching water. However, service delivery should also be augmented with behaviour change programming on the promotion of household water treatment and safe water storage, which is a potentially low-cost option for WASH programming in DPRK.

One difference between MICS and other similar surveys incorporating other SDG water-related indicators (faecal contamination and questions on water availability) was the method for water quality testing. Wagtech Potatest (Palintest, UK) water quality kits were used for this purpose in the 2017 DPRK MICS due to the unavailability of the standard MICS water quality test5 at the time of the survey. The standard MICS water quality testing also utilises a membrane filtration technique-based assay using a custom portable testing kit based on the EZ-Fit system (Millipore) and a selective enzymatic growth media for E. coli (Nissui Compact Dry EC). The choice for the DPRK survey was due to import restrictions of some materials necessary for the water quality testing typically used in MICS. The water quality test used in the 2017 DPRK MICS is based on a technique routinely used for water quality assessments in the field using the same14 and other commercial variants15,16,17 in a variety of contexts. It was felt that this decision did not compromise the quality of the water quality tests. Only 1.1% of the blank control testing resulted in faecally contaminated tests. This is consistent and within acceptable ranges of reported blank testing results of MICS recently conducted in other countries18,19,20,21 that included water quality testing.

The 2017 DPRK MICS allowed for a snapshot of safely managed drinking water service indicators to monitor progress towards SDGs at the national level. It does not provide a substitute for regular monitoring and risk assessments of water supplies. Furthermore, other relevant chemical water quality indicators (e.g., free chlorine residual) and contaminants (e.g., arsenic and fluoride) were not measured, as has been done in other surveys20,22. Given the relatively high use of piped water supplies, the former could be used to evaluate their state of disinfection. There had been no suspected risk of the latter to warrant monitoring of geogenic contaminants of concern. A further survey characteristic to be noted was that the self-reported availability of water in the previous month does not imply continuous availability throughout the day or throughout the year. This issue is a limitation of household surveys such as MICS that do not take into account seasonal effects on the availability of water. Finally, microdata from the 2017 DPRK MICS were not publicly available. This limited the present study to the data available in tabulated format9 and precluded a detailed assessment of correlations between safely managed drinking water service indicators and other factors (i.e., WIG, province, rural vs. urban, etc.).

Results indicated that 93.7% of the population used an improved drinking water source, but when this was combined with the SDG criteria of water availability, accessibility, and safety, coverage was reduced to 92.3, 78.2, and 74.4%, respectively. This resulted in estimates that 60.9% of the population used a SMDWS. The survey results illustrate how the improved SDG indicators can highlight the required gaps to be overcome with regard to universal and equitable access to SMDWS.

Source: Resources - nature.com