While natural hybridization has been widely acknowledged as a powerful evolutionary force6,7, during last decades anthropogenic hybridization considerably contributed to threat the genomic integrity and survival of a number of taxa through the introgression of alien or domestic alleles in the gene pool of natural populations3,11,12,15,41,42,59. In particular, though some studies documented cases of beneficial introgression of domestic mutations in wild populations of North American wolves27 and Alpine ibexes28, introgressive hybridization with domestic forms is globally recognized as a significant risk factor for the conservation of several wild taxa14,24,28,60,61,62. However, though being essential to understand the real impact of the phenomenon and to design sound conservation strategies16,23, the identification of hybrids and their backcrosses remains far from trivial even in the genomic era3,4,5,10,13. In the common practice, the domestic ancestry of biological samples is usually assessed typing their DNA at presumably neutral molecular markers and probabilistically assigning the obtained genotypes to reference parental populations by Bayesian statistics57,63. Consequently, Bayesian assignment values (qi-values) are considered key parameters for management initiatives5,16 and well relate to genomic proportions of parental ancestry estimated by genomic approaches such as the PCA-based admixture deconvolution methods26,64,65.

Nonetheless, detecting admixture signals between subspecies sharing a very recent common ancestry is often hampered by the difficulty to a priori identify pure individuals24,26 and a number of pitfalls may sway the analyses, thus strict criteria should be applied for a reliable identification of admixed individuals: (1) reference parental populations should be composed by the genetic profiles of a sufficient number of individuals (e.g. at least 40 for each reference population5), obtained through the genotyping of high-quality samples at a large number of markers, and lacking any genetic – and possibly morphological – signature of hybrid ancestry; (2) qi-values of unclassified individuals should be estimated by assigning them to parental populations through a repeatable and standardized Bayesian statistical approach; (3) the a posteriori classification of individuals should be based on q-thresholds previously established from the distribution of qi-values observed in simulated genotypes5,33,38.

In this study, we implemented a rapid and efficient standardized workflow (Supplementary Fig. S1) to molecularly detect and classify different levels of admixture in individuals belonging to the Italian wolf population (C. l. italicus), a taxon in which wild x domestic hybridization has been repeatedly documented24,25,26,31,33,37,51,66,67.

The selection of a sufficient number of non-admixed parental individuals to use as reference populations in the assignment analyses was made possible by testing a large national database that includes hundreds of individuals sampled from the entire subspecies distribution range, which had been all formerly morphologically described and molecularly characterized at different sets of genome-wide (STRs and SNPs) markers26,33,52. Therefore, initiatives aiming at systematically collecting population-wide samples of target species should be strongly sustained by national or local authorities, possibly including also samples from nearby populations in order to take into account possible gene flows22,68 and, whenever achievable, detailed information on possible phenotypical anomalies5,24,26.

The simulation of hybrid and backcrossed genotypes, as well as a sufficient number of ancestry-informative markers able to discriminate even closely-related species or subspecies, is then required in order to establish reliable q-thresholds discriminating between different levels of admixture classes5,18,38.

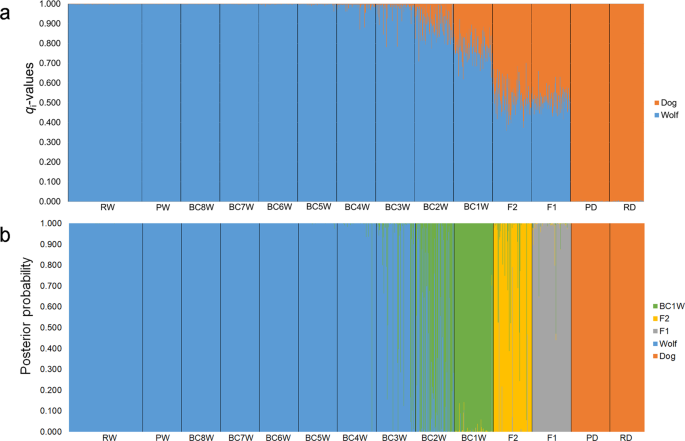

In addition, stable statistical Bayesian approaches, such as that implemented in Parallel Structure55, are strongly recommended to minimize the risk of biased assignment probabilities to an a priori assumed number of populations40, which might occur when sample sizes vary among analyses or when unknown samples with variable levels of admixture (namely including both pure and admixed individuals) are analysed simultaneously instead of one by one40,69,70, conversely to other fully (Structure, NewHybrids, Baps) or partially (GeneClass) Bayesian assignment methods commonly applied for admixture identifications33,41,42,71,72,73,74,75,76. As expected, the “one-by-one” approach with Parallel Structure55 performed reliably, with very limited fluctuations of both Qi and qi among different replicates of the same runs. Up to BC1W, results were also highly concordant with the results obtained from the assignment method implemented in NewHybrids58, despite the very different assumptions and algorithms the two approaches rely on55,58.

Though anthropogenic hybridization has been deeply investigated for a number of animal species, only a few studies applied reliable statistical criteria to define adequate assignment q-thresholds to correctly identify non-admixed individuals and distinguish different admixture classes[1,41,42,73,77. Conversely, most genetic investigations about hybridization in canids were mainly based on q-thresholds selected arbitrarily or chosen among those widely used in the literature (e.g. Malde et al.41) and rarely using simulated data to estimate error rates associated to the choice of a certain threshold31,33,37,66,68,74. A third challenge is thus represented by the adoption of objective criteria based on a Performance Analysis38 for setting the most appropriate q-thresholds to classify individuals into different admixture classes (e.g. pure vs. older admixed vs. recent admixed individuals) that could result into different management categories (e.g. operational pure, introgressed and operational hybrid individuals), minimizing the risk of both type I (pure individuals erroneously identified as admixed animals) and type II (admixed individuals falsely identified as pure animals) errors5,12,16,33,38.

Analysing the 39-STR marker panel, our assignment values appeared strongly robust even when introducing increasingly high levels of allelic dropout and missing data, nonetheless we remind that stringent filters on the quality and reliability of multilocus genotypes are essential to avoid significant biases in all downstream analyses. Our first selected q-threshold allowed us to correctly classify as admixed 100% of F1, F2, BC1W and 71% of BC2W, without any type I error. The remaining 29% of BC2W were classified as pure individuals likely due to a combination of: (i) higher mean qiw, closer to the identified q-threshold (0.955) compared to earlier generations of backcrossing (F1, F2, and BC1W), and (ii) wider CI compared to further generations of backcrossing (BC3W, BC4W, etc.).

Further backcrossing categories showed increasing percentages of assignment as pure individuals (40% in BC3W and 76% in BC4W), clearly showing the limits of the method in our study system when dealing with older backcrossing generations.

Nonetheless, the second empirical q-threshold allowed us to reliably discriminate also between real pure wolves and older admixed individuals, that only show a marginal dog ancestry and possibly deserve additional investigations.

Our results agree with other hybridization studies based on a comparable number of microsatellites, which highlighted the difficulty to reliably detect individuals with a domestic ancestry tracing back to more than two-three generations in the past5,31,33,42,72,78.

When the selected q-thresholds obtained with the 39-STR panel were applied to a large sample (c. 600 genotypes) of putative free-living wolves collected in Italy during the last 20 years, 73.8% of the analysed genotypes resulted operational pure animals (i.e. without relevant signs of domestic ancestor), while 13.5% were classifiable as introgressed individuals and 12.7% as operational hybrids, compatible with multiple and recurrent admixture events that might have occurred trough time, mostly during the phase of population re-expansion26,31,33. However, as shown by simulated data and confirmed by the genetic information derived from the analysis of the uniparental and coding markers, the operational pure category might include a proportion (in our case, 5.8%) of older admixed individuals not reliably detectable using the applied set of molecular markers.

Nonetheless, these percentages of admixed individuals cannot be intended as estimates of prevalence of admixed individuals in the Italian wolf population because the analysed samples had not been randomly collected, but mostly derived from specific monitoring projects focused on hybrid detection and from heterogeneously monitored areas26,31,33,52,56. Conversely, reliable estimates of hybridization prevalence could be assessed through statistical multi-event models applied to capture-recapture data obtained from well-planned long-term genetic and camera-trapping monitoring projects carried out through the entire Italian wolf distribution range79,80,81.

Despite 39 STRs represent a very limited portion of the genetic makeup of the analysed individuals that could be routinely applied to wide monitoring programs, the assignment values of recently-admixed individuals well correlate with those obtained from thousands of genome-wide markers26.

From a management perspective, known limits and efficiency in identifying different admixture classes allow to conceive corresponding management categories as robust as possible. However, a complication in the management of hybrids and backcrosses arises from the use of ambiguous or imprecise terminologies for defining different classes of admixed individuals. Therefore, in this study, we propose to categorize admixed individuals on the basis of empirically-defined q-thresholds, where “operational hybrids” correspond to recent admixed individuals (that include F1-F2 hybrids and most of the first two generations of backcrosses), while “operational pure individuals” correspond either to pure wolves or to older admixed individuals that could not be reliably distinguished from pure ones with the applied panel of molecular markers, but may retain marginal dog ancestry. Between them, we proposed an intermediate assignment class which mostly includes older admixed individuals that cannot be considered as operational pure animals, but do not require priority management actions given their limited domestic ancestry.

Given that hybridization should be primarily counteracted by (i) preventive measures aimed at reducing the number of free-ranging dogs, and (ii) proactive strategies to preserve prey availability, social cohesion, structure and connectivity of wolf packs, since habitat loss, rapid pack turnovers and recent population expansions are known to favor hybridization82, the proposed categorization would permit to avoid management interventions on pure animals erroneously classified as admixed individuals and their negative effects on the genetic and demographic viability of small or threatened wild populations26,47,49,50. Moreover, this categorization would allow to better focus efforts and resources toward “operational hybrids”, which carry significant portions of domestic genome ancestry and likely belong to the first generations of admixture, more efficiently than without any prioritization (e.g. genetically speaking, the removal of one hybrid with 50% dog ancestry would equal to the biological removal of 10 admixed individuals with 5% dog ancestry).

However, in those cases where an active management on operational hybrids is needed, the social acceptability of the applicable methods should be carefully considered, possibly avoiding controversial interventions such as lethal removal3,16,82. Indeed, among other more acceptable management methods, life-long captivation in welfare-respectful structures or sterilization and release of admixed individuals might represent feasible mitigation strategies16,23.

On the other side, the active management of introgressed individuals might become a necessary option where they locally occur at a high prevalence (that can be sometimes much higher than region- or population-wide estimates), thus increasing the probability of interbreeding between hybrids and retaining domestic variants on the long term81,82.

Conversely, dog-derived phenotypic traits, though validated by robust phenotype-genotype association tests26, when found in operational pure individuals should not be considered sufficient reasons for any intervention, since they might reflect old introgression events. Nonetheless they could represent useful clues for identifying potential hybrids with preliminary field surveying methods, such as camera trapping79,80,83, to be followed by further careful genetic investigations.

These classes appear to be more suitable for practical and management purposes compared to categories based on the supposed hybrid generations that, unless they are formally estimated based on genome-wide data26, are largely hazardous since a virtually infinite number of hybrid classes exists, with individual membership proportions widely overlapping.

These findings, together with the results derived from the analyses performed with our 12-STR marker panel, suggest that reduced molecular marker sets and empirical assignment q-thresholds can represent an effective first approach to orientate the most appropriate management actions.

Moreover, the recent possibility to access genome-wide SNP data to investigate anthropogenic hybridisation in a number of taxa7,41,61, including canids24,26,44,77, allows to gain a better resolution on the domestic ancestry proportions and to infer the real generations since the hybridization events26,64,84, that could be needed for the discrimination between real pure and older admixed individuals. Subsequently, the selection of reduced panels of ancestry-informative SNPs, including both neutral and coding mutations26, diagnosable by quantitative or microfluidic PCR techniques77,85,86,87, could be particularly suitable for cost-effective future monitoring projects based on the genotyping of invasive and non-invasive samples to be collected with a standardized design in hybridization hot-spots.

Our workflow, though designed on the case-study of the Italian wolf population, could be easily adapted to monitor the status of other populations and species potentially threatened by anthropogenic hybridization, although each study should adopt ad-hoc q-thresholds, based on the genetic distance between wild and domestic reference populations, their genetic diversity and possible substructure, but also on the number and type of analysed molecular markers. Moreover, when gene flow is known to occur between multiple wild populations (e.g. in Northeastern Alps and Carpathian Mountains88,89,90), the number of reference populations and the optimal number of genetic clusters K should be modified accordingly, in order to avoid the identification of false wild x domestic hybrids (type I errors). Nonetheless, we also remind that such complex systems also require large parental populations to be used as reference. Of course, such an effort is worth using only when dealing with complex levels of admixture, whereas for simpler systems (e.g. when a few individuals could be assigned to recent crosses (F1, F2) or backcrosses (BC1)) standard approaches are sufficient.

In conclusion, the identification of operational categories based on admixture classes outlined through simulations can support scientists, practitioners and decision-makers in the implementation of more efficient conservation strategies mostly focusing on recent hybrids, whose diffusion and consequent spread of domestic alleles could be limited by active management actions to be defined upon local context and acceptance levels toward the presence of free-ranging admixed individuals, but taking into account that nonlethal actions such as captivation or sterilization are often considered by scientists and the public opinion as more feasible and ethically acceptable conservation tools16.

Source: Ecology - nature.com