What do the numbers show

The Cc females that were observed in Akumal were increasingly frequent but decreased in size in the last years of the conservation programme. It is probable that many Cc born on Akumal beaches were recruited to nest, showing philopatric behaviour.

The results show that the Cc nesting in Akumal deposited an increasing number of nests, especially since 2010. Although Mexico’s Protected Area Commission (CONAMP)16 indicated a 5% decline in nesting for Cc between 1995 and 2006 based on the analysis of records from index beaches (i.e., beaches that provide data to estimate the trends for the region), the IUCN reported that data from the Greater Caribbean Recovery Units suggested the opposite11. The Akumal Project corroborated IUCN’s results but showed that turtles preferred the beaches in Akumal for other reasons.

The increase in nesting numbers in Akumal warrants explanation. Marine turtle conservation projects have been increasing in the Caribbean, and accordingly, so have the management skills of the monitors16. Mexico fully prohibited the capture of marine turtles in its waters in 199016,17. As more turtles were protected, more turtles were recruited to the waters and nesting grounds as they reached sexual maturity. The marine turtles that were protected in 1995 in Akumal would reach this maturity after 18/20 years (2013/2015; vide the following section), and in fact, 50% of the analysed data were concentrated after 2013 (the last five years of the project). The monitors working for more than 20 years in the area who marked the marine turtles recorded successful nesting by the same turtles on Akumal beaches approximately 18 years later. This view is also corroborated by Labrada-Martagón et al.6.

Morphometry of nesting females

Chaloupka and Limpus18 studied and defined “age classes” for loggerhead turtles. An adult CCL ranges between 85 and 105 cm. The CCL average in Akumal indicated that the nesting females were adults, though a few small-sized females nested on its beaches. The decreasing average CCL value over the years (Fig. 6) was also observed in other scientific studies; “Karen Bjorndal revealed that somatic growth rates for loggerheads (…) throughout the region began to decline in the late 1990s as the result of an ecological regime shift; the decline continues to the present”19. What does this ecological shift entail? Does increased sea surface temperature accelerate growth and sexual maturity? Will relatively small females with a fast growth rate be observed? Or do the numbers mean that the number of young females in the population increased in the last several years? An increased rate of recruitment for first-time breeders may explain the increase in the population registered in recent years.

Nesting parameters

Nesting success in Akumal was higher than that reported in Guanahacabibes Peninsula, Cuba (67%), which belongs to the same RMU. Nesting success values are probably affected by the tourism pressure on three of the main nesting beaches. Light pollution, obstacles in the sand concentrated in specific areas (such as beach furniture), and people on the beach can lead Cc turtles to abandon their nesting attempts. In some areas of the beach, the sand may be too dry or too thick to excavate, with rocks and coral debris, which also leads turtles to abort their nesting intentions.

The remigration interval was 2.0 years, which is in accordance with other publications (vide Hart et al.12), and Cc takes 12 days on average to re-nest/-emerge in the same nesting season. The analysis showed a very predictable population of nesters exhibiting clockwork-like nesting behaviour. For these turtles, nesting seasons occur precisely every 354.4 days on average. Another aspect revealed by the tag analysis was that the first emergence in a nesting season occurred on the exact same beach as it did in the previous nesting season.

The typical average clutch size for Cc is 100–130 eggs20, meaning that the average clutch size in Akumal (108.6 ± 24.6 eggs) exhibits a large variation. In Florida, the average clutch size for Cc is 98.5 ± 1.7 eggs21, which is smaller than that in Akumal, and in the Archie Carr National Wildlife Refuge along the central coast of Florida, the average clutch size is 113.9 ± 1.4 eggs according to Ehrhart et al.14, which is higher than that in Akumal. High clutch sizes were observed in 2014, but there were no significant differences between the average CCL in this year and the average CCLs in other years in the study period. Hence, the difference in clutch size may be due to causes other than female dimensions, even though there were no significant differences between the clutch size in 2014 and the sizes in other years. These turtles are not particularly large (CCL = 100.2 ± 4.9 cm), but they lay a large number of eggs per clutch.

The average IP for Cc in Akumal was longer (57.2 ± 6.2 days) than the published value of 50.8 ± 1.222, but it was within the range of other studies (46 to 82 days for Matsuzawa et al.23 study). The range of values was high, probably because there was high seasonal variation in the temperature of the sand.

Since the pivotal IP is approximately 52.6 days in the Mediterranean24, one can hypothesize that a balanced ratio of males and females per nest is produced in Akumal. Additionally, the IP depends on temperature fluctuations25. The pivotal temperature for Cc incubation is 28.74 °C26, although Mrosovsky et al.24 determined this value to be 29.3 °C. Another recent experimental study emphasized that the optimal range for Cc incubation was 28.5–31 °C25. Temperatures above 31 °C may impact the hatchling survivorship rate25, which probably explains why some ES values were so low. Humidity, air temperature, and precipitation are probably the main climatic drivers of hatchling production; sea surface temperature and wind speed, though important, do not have significant influences27. It would be very important to determine, for example, the temperature fluctuations in Akumal sand/nests to understand how they affect incubation conditions (are they female-biased with an increasing trend?).

The Cc HS values were similar or even increased when compared to those in other studies (e.g., similar to 87.3 ± 17.8%27; higher than 68% ± 4%21, 55.1 ± 4.0%14), although the ES was decreased and varied most likely due to the difficulties faced by hatchling when leaving the nest. Abiotic factors in Akumal vary due to strong precipitation or flooding due to storms and hurricanes and cause pre-emergent mortality23. In a Florida study, the HS rates for loggerheads decreased from 1985–200321. In a study by Ehrhart et al.14, the HS and ES values were very low due egg washing caused by beach erosion (55.1 ± 4.0%; 53.3 ± 3.7%). On Japanese beaches, the HS determined by Matsuzawa et al.23 was relatively low, which was possibly due to the following conditions: compacted/desiccated sand, hatchlings trapped in the nest due to heat (inhibition of movement), or oxygen deficiency inside the nest due to accelerated metabolic rates23. It is possible that in Akumal, the ES is compromised by one of these constraints; this possibility needs to be further considered.

Conservation implications

Akumal, where snorkelling and observation of nesting females are possible activities for tourists, is certainly important in many aspects8. These opportunities have provided alternative livelihoods for villagers that settled in the region, a pattern observed in other southeastern Mexican coastal locations (vide the Kanzul beach case9) and in other Caribbean locations5.

On the beaches and in the foraging grounds off the southeastern Mexican coast, efforts have been made to enhance the protection of juveniles, females and nests. Activities related to tourism are more efficiently controlled by local environmental authorities28. Additionally, it is very important to improve citizens’ awareness of the recovery and protection of nesting, development and foraging territories. For example, touristic developments should focus on offering information and responsible activities to tourists. The respect of sea turtle habitats and niches by people is crucial. Cc is still vulnerable even with all the apparent recovery suggested by the numbers and indicators and the protection provided by the conservation teams.

To guarantee the success of the Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles agenda in the future, other measures need to be taken. Cases such as those in the Cayman Islands, where migratory green and loggerhead nesting populations are critically reduced13, must be addressed. The protection of all territories and the interconnections among them inside the RMU will provide additional opportunities for population recovery. Additional evidence, such as the results obtained by Blumenthal et al.29, who emphasized that “oceanic juveniles from some rookeries appear to be dispersed among multiple foraging grounds, while those from other rookeries appear to be more locally constrained”, must also be considered to maximize protection.

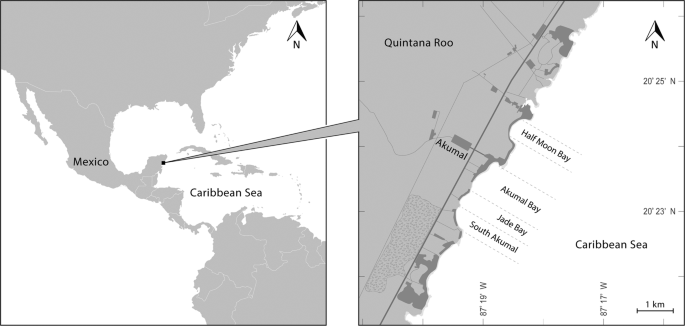

Efforts are needed to identify the role of the rookeries in Akumal and other Quintana Roo regions in supporting the migratory subpopulations/cohorts of the RMU (e.g., for the Florida Atlantic coast, the Gulf of Mexico, the Cuban and Bahamian waters, and even the eastern Atlantic waters10,30,31,32, among other destinations). Field biologists are collecting data and filling gaps to enhance the knowledge of these long-lived species19. The information provided here provides indicators for the Yucatán Peninsula and can be used to compare nesting parameters with other rookeries inside the RMU. Genetic30 or telemetric studies and cross-tagging information analyses are mandatory. These approaches can help reveal the potential connections, genetic drift of genes, molecular diversity and the metapopulation29 structure within the wider Caribbean region. The State of the World’s Sea Turtles (SWOT) has emphasized the need for cooperation among teams.

Source: Ecology - nature.com