Biological model

In the following section, we present the biological model. Parameters’ definition, unit and default value are given in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, and 3.

The biological model describes the dynamics of one or several biological populations of chemotrophic organisms, driven by the growth, birth (division) and death of individual cells. The individual cell life cycle is controlled by catabolic and anabolic reactions occurring within cells17,18,43. Catabolism produces energy used by anabolism for biomass production, which determines cell growth and division; a fraction of energy produced by catabolism is used for cell maintenance. Energy thus flows from catabolism to maintenance and anabolism, and these processes can be described as follows:

$$begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{mathrm{Catabolism}}} hfill & : hfill & {mathop {sum }limits_{i = 1}^n gamma _{S_i}^{cat}S_i to mathop {sum }limits_{i = 1}^m gamma _{P_i}^{cat}P_i + {mathrm{Delta }}G_{cat}} hfill {{mathrm{Maintenance}}} hfill & : hfill & {E_m} hfill {{mathrm{Anabolism}}} hfill & : hfill & {mathop {sum }limits_{i = 1}^{dot n} gamma _{S_i}^{cat}S_i + {mathrm{Delta }}G_{ana} to mathop {sum }limits_{i = 1}^{dot m} gamma _{P_i}^{cat}P_i + B} hfill end{array}$$

(E1)

where Si and Pi are the substrates and products of the metabolic reactions, and the (gamma)’s are the corresponding stoichiometric coefficients. We follow ref. 17 and assume that the average organic compound ({mathrm{C}}{mathrm{H}}_{1.8}{mathrm{O}}_{0.5}{mathrm{N}}_{0.2}) is a plausible approximation for the living biomass B. The energy Em (in kJ d−1) measures the cost of maintenance for a single cell per unit of time. The ∆G terms measure the oxidative power released or consumed by the catabolic and anabolic reactions; they are given by the Nernst relationship:

$${mathrm{Delta }}G(T) = {mathrm{Delta }}G_0(T) + {RTlog} left(mathop {prod }limits_{i = 1}^n S_i^{ gamma _{S_i}}mathop {prod }limits_{i = 1}^m P_i^{gamma _{P_i}}right)$$

(E2)

where R is the ideal gas constant, T is the temperature (in K) and ∆G0(T) (in kJ) is the Gibbs energy of the reaction. ∆G0(T) is obtained from the Gibbs–Helmholtz relationship:

$${mathrm{Delta }}G(T) = {mathrm{Delta }}G_0(T_S)frac{T}{{T_S}} + {mathrm{Delta }}H_0(T_S)frac{{T_S – T}}{{T_S}}$$

(E3)

where TS is the standard temperature of 298.15 K. Note that equations (E2) and (E3) describes how the thermodynamics of any given metabolism (i.e., the combination of catabolism and anabolism) vary with temperature.

Michaelis–Menten kinetics apply to catabolism:

$$q_{cat} = q_{max}frac{{min(S_i^{cat}/gamma _{S_i}^{cat})}}{{min(S_i^{cat}/gamma _{S_i}^{cat}) + K_S}}$$

(E4)

where KS is the half-saturation constant, qmax the maximum metabolic rate of the cell (d−1), and (min(S_i^{cat}/gamma _{S_i}^{cat})) measures the concentration of the limiting substrate (taking stoichiometry into account). The energy produced is first directed toward maintenance. The cell energetic requirement for maintenance is:

$$q_m = frac{{ – E_m}}{{{mathrm{Delta }}G_{cat}}}$$

(E5)

The cell therefore meets its energy requirement only if qcat > qm. If the cell does not meet this requirement, the basal mortality rate of the cell, m, (in d−1), is augmented by a decay-related mortality term equal to (k_d(q_m – q_{cat})). Hence the actual mortality rate:

$$begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {If,q_{cat} ,<, q_m} hfill & : hfill & {d = m + k_d(q_m – q_{cat})} hfill {If,q_{cat} ,> , q_m} hfill & : hfill & {d = m} hfill end{array}$$

(E6)

When the energy requirements for maintenance are not met (qcat < qm) no energy is allocated to biomass production. Conversely, when those requirements are met (qcat < qm), then the energy remaining after allocation to cell maintenance can be directed to anabolism. A constant quantity of energy({mathrm{Delta }}G_{diss}) (in kJ) is then lost through dissipation. Following ref. 17 we consider the following empirical relationship:

$${mathrm{Delta }}G_{diss} = 200 + 18(6 – NoC)^{1.8} + e^{( – 0.2 – alpha )^{2.16}(3.6 + 0.4NoC)}$$

(E7)

where NoC is the number of carbons in the carbon source used by the anabolic reaction, and (alpha) is its degree of oxidation. The efficiency of metabolic coupling (i.e., the number of occurrences of the catabolic reaction to fuel one occurrence of the anabolic reaction once the maintenance cost has been met) is then measured by

$$lambda = frac{{ – {mathrm{Delta }}G_{cat}}}{{{mathrm{Delta }}G_{ana} + {mathrm{Delta }}G_{diss}}}$$

(E)

The Michaelis–Menten kinetics of anabolism is given by

$$begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {If,q_{cat} ,> , q_m} hfill & : hfill & {q_{ana} = lambda (q_{cat} – q_{m})frac{{min(S_i^{ana}/gamma _{S_i}^{ana})}}{{min(S_i^{ana}/gamma _{S_i}^{ana}) + K_S}}} hfill {If,q_{cat} ,<, q_m} hfill & : hfill & {q_{ana} = 0} hfill end{array}$$

(E9)

where the half-saturation constant KS independent of the substrate, as was assumed in ref. 43. As biomass accumulates in the cell at rate qana, cell growth may lead to cell division. The cell division rate, r, is given by:

$$begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {If,B ,<, 2B_{Struct}} hfill & : hfill & {r = 0} hfill {If,B ,> , 2B_{Struct}} hfill & : hfill & {r = r_{max}frac{1}{{1 + e^{ – theta log10((B – 2B_{Struct})/B_{Struct})}}}} hfill end{array}$$

(E10)

This means that a cell cannot divide if its internal biomass is not at least twice its cell structural biomass so that the two daughter cells meet this structural requirement. Above this threshold value of 2BStruct, r is of sigmoidal form so that the division rate first increases exponentially with the intracellular biomass content then saturates to rmax when biomass is largely available.

Using the rates of catabolic and anabolic cell activity and resulting cell division and mortality rates, we derive the following system of ordinary differential equations driving the cell population dynamics (dynamics of the number of cells and average cell biomass) and the feedback of the population on its environment (chemical composition of the ocean surface):

$$begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {frac{{dN_i}}{{dt}}} hfill & = hfill & {(r_i – d_i)N_i} hfill {frac{{dB_i}}{{dt}}} hfill & = hfill & {q_{ana_i} – r_iB} hfill {frac{{dX_j}}{{dt}}} hfill & = hfill & {F(X_j) + mathop {sum }limits_{i = 1}^{MT} (q_{cat_i}gamma _{i,X_j}^{cat} + q_{ana_i}gamma _{i,X_j}^{ana})N_i} hfill end{array}$$

(E11)

where MT denotes the ensemble of metabolic types considered, Ni is the number of individual cells in a population of a given metabolic type, Bi is the average cellular biomass of that type, and (X_1,…,X_S) are the concentrations of all relevant chemical species in the environment. The term ({sum }_{i = 1}^{MT} (q_{cat_i},gamma _{i,X_j}^{cat} + q_{ana_i}gamma _{i,X_j}^{ana})N_i) describes how concentrations vary according to the biological activity of each biological population i in the microbial community. The F(Xj) terms describe the environmental forcing resulting from ocean circulation and atmosphere-ocean exchanges as simulated by a stagnant boundary layer model as in ref. 13. The system of equations (E11) is solved numerically using a forward Euler method.

The flow of energy through the cell is driven by the maximum metabolic rate, qmax (in d−1), and the rate of energy consumption for maintenance, Em (in kJ d−1). They are both expressed as functions of temperature and cell size of the form ea+bTVc. Default values for parameters a, b and c entering qmax and Em are given in Supplementary Table 2.

The structural cell biomass BStruct increases with cell size according to BStruct = aVb. Both metabolic rate and maintenance cost increase with cell size, but not as fast as structural biomass. Consequently, the biomass specific rates of metabolism and energy consumption for maintenance decrease with cell size. Thus, small organisms are better at acquiring energy, but large organisms are more cost efficient due to lower maintenance requirements. A trade-off mediated by cell size thus exists between metabolic and maintenance rates, hence an optimal (intermediate) cell size, which is consistent with previous work conducted on unicellular marine organisms22. Both metabolic and maintenance rates increase with temperature, but the metabolic rate increases slightly faster19,20, shifting the trade-off toward larger sizes. As a consequence, the optimal cell size increases with temperature.

To compute the evolutionarily optimal cell size for a given metabolic type at a given temperature, we run simulations across a range of cell size and measure the level of resource use at equilibrium given by (Q^ ast = mathop{prod}limits_{i = 1}^n {S_i^{ gamma _{S_i}^{cat}}} mathop{prod}limits_{i = 1}^m {P_i^{gamma _{P_i}^{cat}}}), the product of the metabolic substrates and wastes concentrations at equilibrium weighted by their stoichiometric coefficient. According to the classical principle of “pessimization” (maximization of resource use)44,45,46, populations that are better at exploiting their environment have lower Q* and evolution by natural selection will favor the cell size that minimizes Q*, thus leading to the evolutionarily optimal cell size. Supplementary Fig. 9 shows Q* as a function of cell size and temperature for the H2-based methanogenesis.

The optimal cell size, SC*, follows a positive relationship with temperature given by SC* = 10a+bT. We consider that over geological time scales, adaptive evolution acting on genetic variation among cells is fast enough so that SC is equal to SC*. As temperature changes, evolutionary adaptation by natural selection tracks the temperature-dependent optimal cell size.

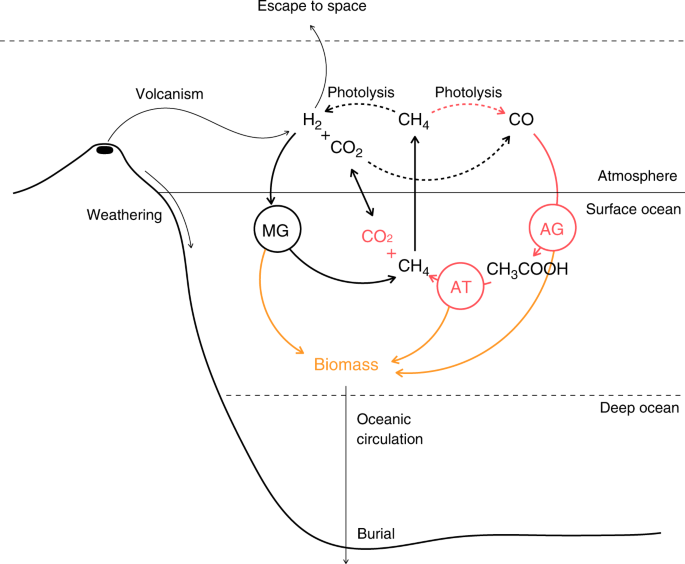

In contemporary Earth oceans, most of the dead biomass is recycled by fermentors (>99%), and the rest is buried into the ocean floor. Although the most general version of our model includes populations of acetogenic biomass fermentors and acetotrophs, their inclusion considerably increases simulation time (results not shown). All the results presented in the main text have been obtained without fermentors, assuming that the dead biomass accumulates in the ocean’s interior. It appears that biomass productivity is so low that the effect of biomass recycling (or lack thereof) on the atmospheric composition is negligible. We verified this by testing the effect of a recycling pathway in each ecosystem (MG, AG + AT, MG + AG + AT), for an intermediate value of H2 volcanic outgassing. Although biomass production is sufficient to sustain a population of fermentors, we found no significant effect of their biological activity on the atmospheric composition. Additionally, when we can compare the global atmospheric redox budget of the planet with and without biomass production (see Supplementary Results and Discussion, Supplementary Fig. 12), we find no significant differences. This further demonstrates that biomass production and the accumulation of dead biomass in the absence of remineralization represents a sink of C and H that is marginal compared to the other fluxes in the model. Note that the situation would be very different after the evolution of more productive, photosynthetic primary producers.

Because we do not model the fate of dead biomass explicitly, we evaluate the consistency of our predictions of biomass production with the geological record (carbon isotopic fractionation data) by taking biomass production as the upper bound for burial (in which case 100% of the produced biomass is ultimately buried) and using the modern value of burial (taken to be 0.2% as in e.g., ref. 13) as lower bound.

Planetary model

Our computation of climate state and mean surface temperature is based on 3D simulations with the Generic LMD GCM4,47,48. The model includes a 2-layer dynamic ocean computing heat transport and sea ice formation49. The radiative transfer is based on the correlated-k methods with k-coefficients calculated using the HITRAN 2008 molecular database. We used the simulations described in ref. 4 for the early Earth at 3.8 Ga, assuming no land, 1 bar of N2 and a 14 h rotation period. The simulation grid covers a range of pCO2 from 0.01 to 1 bar and pCH4 from 0 to 10 mbar. From this grid, we derived the following simple parametrization of the mean surface temperature as a function of pCO2 and pCH4 (expressed in bar):

$$Tleft( {! deg {mathrm{C}}} right) = – 19.26 + 77.67 {sqrt {p{mathrm{C}}{{mathrm{O}}_2}}} ,,+, 5{mathrm{log}}10left( {frac{{1 + p{mathrm{C}}{{mathrm{H}}_4}{{10}^6}}}{3}} right)$$

(E12)

In the coupled biological-planetary model, we assume that the climate is always at equilibrium, meaning that the timescale of climate convergence is shorter than biological and geochemical timescales.

Photochemistry is computed with the 1D version of the Generic LMD GCM, which now includes a photochemistry core from ref. 50. The chemical network includes 30 species (mostly hydrocarbons) and 114 reactions. We use the reactions from ref. 50 for H2-H2O-CO2 and from ref. 51 for hydrocarbons. The photochemistry model also includes a pathway for the formation of hydrocarbon aerosol (C2H + C2H2 → HCAER + H)51,52.

We use the eddy diffusion vertical profile from ref. 53 and the solar UV spectrum at 3.8 Ga from ref. 54. Boundary conditions are set by the mixing ratios of CO2, CH4, and H2O at the first atmospheric layer. The atmospheric CO is either consumed biotically by acetogens when they are present in the biosphere, or abiotically by the formation of formate in the ocean (resulting in a deposition velocity of ~108 cm s−1) as in ref. 13,55. This eliminates the possibility of CO-runaway, which otherwise occurs in our simulations at high level of H2 or CO2. In addition, we assume that H2 undergoes diffusion-limited atmospheric escape (see for instance ref. 13).

We performed simulations across a range of pCO2 (104–105 ppm), pCH4 (1–104 ppm), H2 (100–104 ppm). For our range of atmospheric composition, photochemistry is dominated by the photolysis of CO2 and CH4, whose net reactions are:

$${mathrm{CO}}_2 + {mathrm{H}}_2 = {mathrm{CO}} + {mathrm{H}}_2{mathrm{O}}$$

(R1)

$${mathrm{CH}}_4 + {mathrm{CO}}_2 = 2{mathrm{CO}} + 2{mathrm{H}}_2$$

(R2)

From the simulation outputs we derived simple parametrizations for the production rates and loss rates of CH4, CO, H2 (see Supplementary Fig. 10). The reaction rates of (R1) and (R2) can be parameterized respectively as (in molecules cm−2 s−1):

$$F_1 = 1.8,10^{10} cdot left( {frac{{p{mathrm{C}}{mathrm{O}}_2}}{{10^{ – 1}}}} right) cdot left( {frac{{p{mathrm{H}}_2}}{{10^{ – 4}}}} right)^{0.4}$$

(E13)

$$F_2 = 2,10^{10}left( {frac{{p{mathrm{C}}{mathrm{O}}_2}}{{10^{ – 1}}}} right)^{ – 0.2} ,cdot, left( {frac{{p{mathrm{H}}_2}}{{10^{ – 4}}}} right)^{ – 0.2} ,cdot, left( {frac{{p{mathrm{C}}{mathrm{H}}_4}}{{10^{ – 4}}}} right)^u$$

(E14)

where u (between 0.5 and 1) is given by

$$u = 0.6 + 0.1{it{{mathrm{log}}}}left( {frac{{p{mathrm{H}}_2}}{{10^{ – 4}}}} right) – frac{{{it{{mathrm{log}}}}({it{p{mathrm{C}}{mathrm{H}}}}_4) + 2}}{{15}} + 0.08log left(frac{{p{mathrm{C}}{mathrm{O}}_2}}{{10^{ – 1}}}right)$$

(E15)

To simulate the evolution of pCO2 with time and feedbacks between the microbial community, climate, and the carbon cycle, we use a simple carbon cycle model based on ref. 5. The model computes the evolution of atmospheric CO2, dissolved inorganic carbon (CO2, HCO3− and CO32−) and pH in the ocean and in seafloor pores. The model takes into account outgassing (from volcanoes and mid-oceanic ridges), continental silicate weathering, dissolution of basalts in the seafloor, and oceanic chemistry, as sources and sinks of CO2. For all parameters in the carbon cycle model, we use the mean values given in ref. 5. For the temperature dependences of silicate weathering and oceanic chemistry, we use the mean surface temperature from our climate model. Even though this model only computes global mean quantities and does not take into account the organic matter in carbon sources and sinks of carbon, it is computationally very fast and well suited for studying the major feedbacks between biological populations and the atmosphere and climate.

Coupled biological-planetary model

The model resolves dynamics that take place on extremely different timescales—geological processes are extremely slow (103–106 years) compared to biological dynamics (days to years). We use a timescale separation approach and assume that the planetary environment is fixed on the biological time scale, and the biological system (population and local environment) is at ecological and evolutionary equilibrium on the geological time scale. This allows us to resolve the biological and geological dynamics separately and couple them at discrete points in time.

The biological dynamics are first resolved by the biological model for a fixed environmental forcing (equations (E11)), with microbial cells at their evolutionarily optimal size. The biological model is integrated over a sufficiently long time so that the local ecosystem reaches its equilibrium. Then we compute the biogenic fluxes between the surface ocean and the atmosphere, and between the surface ocean and the deep ocean, and feed them into the planetary model. The planetary model is then used to resolve the system’s geochemical and climate dynamics, but only for a sufficiently small change in the planetary state (1% to 1‰ variation of the state variable that changes the most) so that this change would alter the biological equilibrium only marginally. The new biological equilibrium is then computed, and the process is re-iterated. This iterative process approximates a continuous coupling between the microbial community and its planetary environment.

Monte-Carlo simulations

We explore the parameter range by stochastically varying the parameters that determine the maximum metabolic rate, the rate of energy consumption for maintenance, the metabolic half-saturation constant, the decay and mortality rates, and the maximum division rate. We also vary the values of the parameters that shape the dependencies on size, temperature, and cellular biomass (see Supplementary Table 4). Parameter values are picked uniformly or log-uniformly (to avoid making prior assumptions on the likelihood of specific regions of the parameter space) within ranges constrained by empirical data from the literature, or large enough to cover plausible empirical variation. Three thousand simulations were run for the MG ecosystem, one thousand for the AG + AT ecosystem, and one thousand for the MG + AG + AT ecosystem, under four different values of volcanic outgassing: (phi _{{mathrm{Volc}}}({mathrm{H}}_2)) = 2 × 109.5, 2 × 1010, 2 × 1010.5, and 2 × 1011 molecules cm−2 s−1, hence a total of 20,000 simulations. Each simulation was run to equilibrium.

The results can be divided into two subsets of roughly equivalent size, regardless of the ecosystems and volcanic activity considered: those with biological activity and those without (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). We then verified that the number of simulations run for each of the considered scenarios was sufficient for the resulting distribution of equilibrium states to have converged. We evaluated convergence by subsampling, for each scenario, the subset of ‘biologically viable’ simulations with increasing sample size, and computing the average equilibrium biomass and CH4 biogenic emission of the subsamples. The results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 for the three scenarios and for (phi _{{mathrm{Volc}}}({mathrm{H}}_2)) = 2 × 1010.5 molecules cm−2 s−1.

Source: Ecology - nature.com