As expanding human populations are transforming environments at unprecedented rates, understanding the linkages between human and animal behaviour is of critical importance. It is key to preserving global biodiversity, to maintaining the integrity of ecosystems, and to predicting global zoonoses and environmental change5. This knowledge is not only worth billions of dollars, but it is also vital for shaping a sustainable future. So far, however, researchers have had to rely predominantly on purely observational approaches.

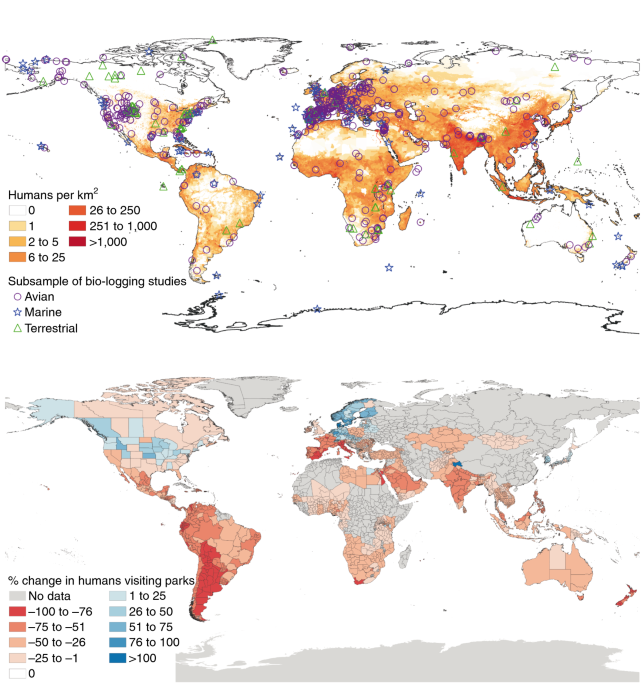

Scientists have long sought to quantify how humans impact various aspects of animal biology, such as population levels, reproductive and mortality rates, movement and activity patterns, foraging behaviour, and stress responses1,6,7,8. Studies usually employ one of two main approaches — spatial comparisons or temporal analyses. The first involves comparing a species’ biology across areas that differ in human activity. Such differences occur, for example, along urban gradients, with increasing distance from coastlines, or between protected and unprotected areas. The second approach documents how animals respond to temporal changes in human activity in a given locality, which may be short-term6 (for example, holiday periods, or natural or human-made disasters) or longer-term (for example, changes in protection status, or land- or seascape modification through construction).

The reduction in human mobility on land and at sea during the anthropause is unparalleled in recent history9,10. Lockdown effects have been drastic, sudden, and widespread. Countries have also responded in broadly similar ways across large parts of the world, presenting invaluable replicates of this perturbation. So, how exactly can we make the most of these exceptional circumstances?

While every field study has value in its own right, the pandemic affords an opportunity to build a global picture of animal responses by pooling large numbers of datasets. Such collaborative projects can integrate the spatial and temporal approaches outlined above, in an attempt to uncover causal relationships. Aspects of animals’ biology can be compared across sites that vary in COVID-19-related restrictions and resultant changes in human mobility, and across different time periods, spanning from before until after changes occurred. Taking into account additional data from unaffected ‘control’ sites11, such as particularly remote or inaccessible areas, researchers will be able to examine if, and how, animals responded to reductions in human activity. Baseline data from similar time periods in prior years, and from years following the COVID-19 pandemic, will considerably strengthen inferences, helping to disentangle anthropause effects from natural seasonal variation in animal biology.

Finally, we wish to share a very important sentiment. While this is no doubt a valuable research opportunity, it is one that has only come about through tragic circumstances. Scientists who prepare to study lockdown effects on wildlife, and on the environment more generally, should be sensitive to the immense human suffering caused by COVID-19 and use appropriate language to describe their work.

Source: Ecology - nature.com