The Chrysophyceae, commonly referred to as golden-brown algae, is a diverse, cosmopolitan, and ecologically significant group of heterokont algae that is especially important in freshwater ecosystems1,2,3,4. Species are mostly microscopic, planktonic or attached, autotrophic, heterotrophic or mixotrophic, naked or with a cell covering, motile or non-motile, and the class embraces numerous vegetative forms3,5. Synurophytes are a monophyletic clade of chrysophytes that construct a highly organized covering around the cell composed of distinctive siliceous scales3.

As is true with all members of the Chrysophyceae6,7, synurophytes are capable of forming a siliceous stage known as a stomatocyst, statospore, or more commonly a cyst, that serves as a resting stage in the life cycle of the species3,8. Cysts are presumably produced as a result of either asexual or sexual reproduction1,4,9, and their formation is often triggered by sudden changes in environmental conditions, predation pressure6,10, or in the case of sexually-produced cysts, population density4. Cysts form a seed bank and when conditions once again become favorable for growth, they germinate to initiate a new population.

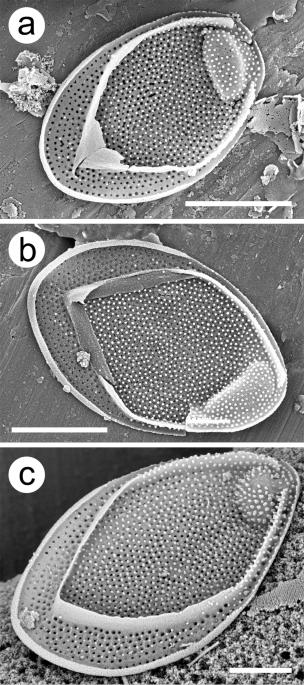

Cysts are hollow structures, often more or less spherical in shape, with a single germination pore, that are formed endogenously within a silica deposition vesicle (SDV)1,3. The SDV takes the shape of the cyst, enclosing a large percentage of the cell cytoplasm, including the nucleus and other vital organelles. The cyst wall forms within the SDV in what is thought to be a two-step process11,12. The first step involves the deposition of an inner wall, which is unornamented, morphologically similar for many species, and often different in appearance from the mature cyst3,11. Additional outer wall layers comprise the second step of cyst formation. In some cases, the final layer simply results in a smooth outer surface. In other cases, additional wall ornamentation is added and, if present, a collar constructed. The collar is a specialized structure that surrounds the cyst pore, the latter of which becomes plugged with an organic material during the final stages of cyst maturation.

Details describing cyst morphology are given in Duff et al.8 and Wilkinson et al.13. Briefly, cysts have anterior and posterior hemispheres, divided by an equator, with the pore usually being situated atop of the anterior hemisphere. Although the majority of cyst types are spherical, there is a wide diversity of shapes, including oval, ovate, oblong, as well as flattened pancake forms. Pore openings are almost always circular, but the inner sides can be straight, conical or concave. Pores may be simple or surrounded by a thick and continuous rim of silica called the collar. Collars may be simple or complex, the latter consisting of two or more separate collars surrounding the pore in a concentric fashion. The outer wall of the cyst can be smooth, or consist of a multitude of different types of elements, including papillae, nodules, spines, ridges, reticulation designs and depressions. The ornamentation of the mature outer wall and the pore-collar complex is of taxonomic importance6,8,11,12,13.

Since the morphology of a mature cyst is specific for a given species, the remains of a cyst type can indicate the presence of that species in a given waterbody. Since many chrysophyte species are found under specific environmental conditions3,5, the remains of their cysts can serve as valuable paleoindicators9. Cysts have been used to reconstruct a range of environmental parameters, including nutrient conditions14, pH15,16,17, specific conductivity18,19 and climate7,20,21. Since cysts are also found in the fossil record as far back as the Late Triassic22, they also represent potential proxies for reconstructing the geologic past. Hundreds of cyst morphotypes are known, but the vast majority have not been linked to specific clades or actual species1,6, inhibiting their full use as bioindicators.

The fossil synurophyte species Mallomonas ampla Siver & Lott was described from an early Eocene Arctic deposit, the Giraffe Pipe locality23. Although this taxon is extinct, a closely related modern species, Mallomonas neoampla Gusev & Siver, was recently described from tropical Vietnam24, and both of these taxa are closely related to another modern species, M. multisetigera Dürrschmidt25. The cyst is not known for either of the living species. Recently, numerous cysts still bearing scales belonging to M. ampla were uncovered from the Giraffe Pipe fossil locality. The purpose of this study is to document and describe the cyst produced by M. ampla, and to discuss the remarkable and unique conditions under which these fossils were formed.

Source: Ecology - nature.com