Ina Vandebroek: a revolution is needed in how we communicate and collaborate

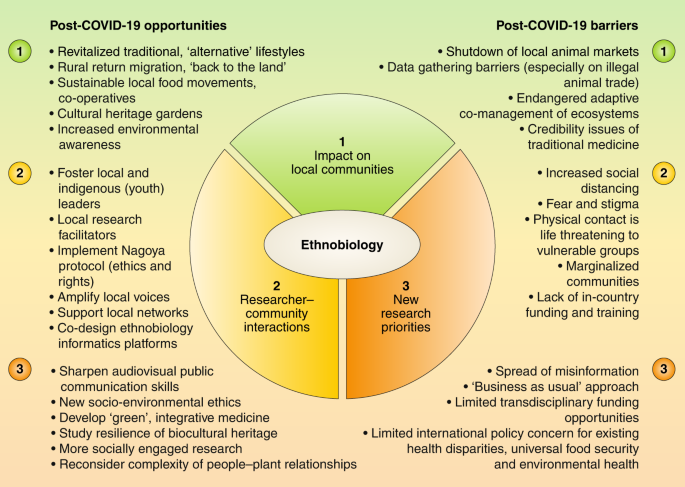

The COVID-19 crisis shows a real need for better mainstreaming of scientific facts and important lessons learned from ethnobiology research to counter the spread of misinformation. This amplified communication strategy will also drive much-needed continued attention to urgent global challenges many ethnobiologists are studying, ranging from the worldwide decline in biological and cultural diversity to health disparities faced by immigrant communities in urban environments. Ethnobiologists are doing a great job of communicating to their peers. Now they will also have to sharpen their audiovisual communication skills to reach those outside the scientific community more effectively and more often.

In addition to better shaping the public dialogue, the post-COVID-19 world will hopefully also see a concerted action from ethnobiologists in advocating for increased funding for international and transdisciplinary collaborations, cutting across existing barriers in the social and natural sciences and across geopolitical boundaries34. Unfortunately, in many countries, funding for these two divisions is still operating in parallel, with scarce cross-pollination. A similar limitation exists for geographical funding opportunities, which are too often restricted to predefined regions or countries. Such limitations significantly hamper joint ethnobiology research in today’s globalized world. Collaborations between researchers and community members should also become more visible, so that community voices are increasingly heard instead of being interpreted by scientists. Breaking down these walls will require coordinated action. If the COVID-19 crisis is showing us that we are all connected, we should use this as an opportunity to communicate and collaborate more intensely than ever.

Ana Ladio: ethnobiology studies raised the alarm about the socio-environmental crisis and now provide a foundation for a new set of socio-environmental ethics

Ethnobiology has often been described as a naive science, and misunderstood to be a discipline that yearns for the old ways of the indigenous cultures of the world. One of our main focuses has been to study these cultures’ health and food systems. These systems are based on self-sufficiency and agroecological concepts, and rooted in non-exploitative relational models (sensu35) with an ethical commitment to renewing natural cycles. Those who follow these relational models know without a doubt that their destiny is irrevocably connected to the destiny of Mother Earth. The COVID-19 crisis shows us that the ethnobiology research carried out in these communities provided an early warning to the current socio-environmental crisis. The main causes for this pandemic have been the imposition of unscrupulous global market logic based on actions such as the indiscriminate destruction of forests, the use of damaging agrochemicals in industrial agriculture and, in particular, the illegal trafficking of wild species. The lack of food and health autonomy in urban centres, with inhabitants who no longer relate to nature, makes these areas highly vulnerable in this crisis. Therefore, after COVID-19, ethnobiology should have a much stronger role to play, proclaiming loudly to the world the ethical guidelines to be followed, which we learned from the indigenous peoples36. Ethnobiology should be an essential instrument in this new stage, with a call to reflect and sustain, with scientific evidence, a new conception of human health interconnected with the sustainability of the biosphere.

David Picking and Rupika Delgoda: ethnomedicine fit for the twenty-first century — a post-COVID-19 perspective

The Caribbean, like many regions in the Global South, faces significant health inequalities and potentially catastrophic repercussions from the health and economic impact of COVID-19. The region does, however, benefit from its unique biodiversity and rich culture of ethnomedicine37. At this time, perhaps more than ever, it is imperative that these are fully developed for the greater good. Cuba, by example, is unique in the region in its development of ‘green medicine’, providing a compelling illustration of scientific and traditional medicine merging. Cuba’s green medicine focuses on prevention before intervention, reducing reliance on pharmaceutical drugs and keeping medicine close to the communities it serves38.

Partnering collaboratively and equitably with communities and traditional knowledge holders continues to hold potentially valuable insights into many of today’s health challenges. While nature-based searches have and continue to inspire the development of treatments for a wide range of diseases39, COVID-19 delivers an urgent call to prioritize funding and innovative research methods for traditional medicines. Examples include the use of systems biology and reverse pharmacology to improve and confirm the efficacy and safety of Argemone mexicana L., a traditional treatment for malaria in Mali40.

A post-COVID-19 world presents an opportunity for a reboot, a re-evaluation and a re-envisioning of healthcare, the development of medicines that come from and are available to those in the Global South, and the development of a green, integrated or ethnomedicine fit for the twenty-first century.

Alfred Maroyi: COVID-19 — a need to highlight its biological and socio-cultural dimensions

In the advent of globalization, human travel, trade and transportation increased, and the outbreak of COVID-19 underscores the need to develop prevention protocols towards safeguarding public health. Pharmacological research done over many centuries aimed at developing new microbial vaccines has failed to develop effective preventive viral vaccines and effective antiviral therapies. The unique biology of viruses makes it difficult to develop viral vaccines, as some viruses have very high mutation rates. Therefore, collaboration between researchers is required to shed more light on COVID-19 and human–virus interactions. In ethnobiology research, ethnopharmacological insights and socio-cultural factors are all important in the management and control of the COVID-19 outbreak. Since COVID-19 is widespread and a major public health problem, it is important to understand the broader social and cultural contexts that contribute to the experiences of affected persons, their families and their communities, including the role of socio-cultural factors such as inequality, informal settlements, inadequate health care systems and cultural beliefs in the spread and/or prevention of the epidemic. This is particularly important in South Africa and other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, where rural and urban communities have historically faced different public health challenges. Socio-cultural factors often associated with rural communities include poverty, poor sanitation, illiteracy and social stigma of infectious diseases. Therefore, public health interventions aimed at combating COVID-19 should also address the socio-cultural factors associated with the rural–urban divide.

Cassandra L. Quave: a new look at traditional health strategies in the aftermath of COVID-19

The rapid emergence of COVID-19 has put a tremendous strain on Western systems of medicine across the globe, overwhelming healthcare personnel and medical supply chains, especially in urban centres. Strategies have been overwhelmingly reactive, rather than proactive, both in tracking and treating cases. Individuals with underlying chronic health conditions have been among those at greatest risk, highlighting the importance not only of chronic disease prevention, but also health promotion and maintenance. Across many cultures, traditional systems of medicine put great emphasis on proactive health measures rather than reactive critical care. Yet the scientific basis of many traditional medical interventions remains poorly understood; this includes pharmacological activities of foods and medicines, as well as the psychological impacts of ritual practices on health and well-being. Medicinal plants are fundamental to the pharmacopoeia of many traditional medical systems, and while an estimated 28,187 species have been documented for use in plant-based medicine41, most have not been evaluated using modern laboratory techniques. Ethnobiologists are poised to make important contributions to the documentation, evaluation and dissemination of traditional health strategies. Collaborations between scientists across diverse disciplines, including ethnobiology, chemistry, microbiology, pharmacology, psychology, immunology and more, can open up new paths to enriching medical resources and shifting paradigms towards more holistic care across the world. Moreover, ethnobiologists can serve as key connectors between local stakeholders and scientists, facilitating pathways for equitable access and benefit sharing. At a time when the public has lost much control over their health and well-being, the need for a deeper understanding of intercultural health paradigms42 has never been greater.

Guillaume Odonne: ethnobiology in motion — COVID-19 as a trigger to consider the dynamics and resilience of biocultural heritage

Local knowledge is never fixed, since cultural groups exchange, wage war, dissolve and reconstitute over time. Some groups experienced collapses, as did most of Americas’ peoples in the past 500 years43. Among those communities still surviving, a high biocultural resilience arose to radical change, and this must be understood as a major cultural trait44. Adaptation mainly concerns cultural relationships to changing ecosystems, but also to the pathosphere (the global panorama of surrounding pathogens), driving changes in people’s religious, medicinal and sociocultural systems. The COVID-19 pandemic is a unique opportunity to switch from a fixist to a dynamic view of ethnobiological knowledge. Deciphering the mechanisms of changes in biocultural heritage might help to better understand these societies than through recording lists of species that become often obsolete in the next few decades, since medicinal floras worldwide are full of alien species45.

Documenting biocultural dynamics through time thus needs an urgent and long-term investment in fundamental research. As an example, during the last five years, the Teko people from French Guiana, with a population of ~500 people, lost 20% of their elders, which means a significant decrease in the biocultural heritage of this community. The COVID-19 pandemic, which particularly affects elderly persons, will likely erase a substantial part of humanity’s biocultural heritage worldwide. It is therefore crucial to invest in its interdisciplinary and participatory inventory and to decolonize methods, so that research is conducted in an intercultural and respectful way, and towards mutual benefit46. Ethnobiology as an academic science owes this to local knowledge.

Ulysses Paulino Albuquerque: towards a more rigorous and socially engaged ethnobiological science

The community of ethnobiologists has long advocated more theoretical and methodological rigor in the research being carried out. The discussion about the dichotomy between quantitative versus qualitative research, for example, is already out of date. We concluded that we need to overcome the phase of traditional surveys to answer questions that are original, relevant and have some importance (whether theoretical or applied). In a post-COVID-19 world, these questions are even more important. Scientists will be increasingly demanded to produce relevant knowledge, either to advance science or to improve people’s quality of life. The association of COVID-19, as well as other diseases, with human patterns of use of biodiversity (regardless of scale), poses significant challenges for ethnobiologists, such as (1) the planning and execution of studies on broad geographical scales; (2) the need to act more and more in cooperation, uniting different skills and expertise; and (3) the carrying out of the movement to unite knowledge from different areas of science through the active participation of different professionals. In a post-COVID-19 world, ethnobiologists will face major changes in social dynamics, which will influence field activities, migrations, emergencies and the re-emergence of diseases. Also, we will need to respond to other challenges that ethnobiologists should address, including climate change and its effects on biocultural diversity. The post-COVID-19 world makes the definitive invitation for ethnobiologists to review their research agendas.

Julio A. Hurrell, Patricia M. Arenas and Jeremías P. Puentes: re-thinking ethnobiology — the challenges of complexity

It is difficult to assess the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic when we are still going through its evolution. However, several omens for the post-COVID-19 global scenario regarding health, social and economic aspects, among others, are discouraging. In this context of uncertainty, many local ethnobiological investigations have already encountered problems, especially with field work (interruption of surveys or loss of collaborators among others) due to the often mandatory quarantines affecting both researchers and collaborators. We have suspended our own work in urban ethnobotany with Chinese immigrants in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires, Argentina. In recent years, pre-COVID-19, ethnobiology has shown an intense development of theoretical and methodological issues that were forcing a re-evaluation of the discipline, which has made evident the intrinsic complexity of ethnobiology’s object of study, the web of relationships between people and their biological environments within the framework of biocultural systems. This implies, for example, re-thinking nature and culture as a unit (not as separate pathways), or re-considering interviews as communication systems that generate meaning (not as mere information exchange). This recursive reflection would help to give new meaning to ethnobiology after the COVID-19 crisis, which should not only be understood as a ‘catastrophe’ but as a ‘decision’ or ‘critical judgment’; that is, an opportunity for change.

Source: Ecology - nature.com