Applying metabolic scaling theory to the megabiota

Ultimately, cellular metabolism sets the pace of life and controls the flux of matter and energy in the biosphere32. The scaling of organismal metabolism powerfully constrains the functioning and life history of organisms across organisms from small to large sizes33,34,35. The scaling of metabolism sets the demand for resources, the space organisms require to forage, and the rate at which they interact with other organisms. Metabolism also influences the flux of energy and nutrients through organisms, populations, and ecosystems33,36. It constrains the rate of disease progression37, the magnitude of how organisms interact with each other and their environment and influences their risk of extinction18.

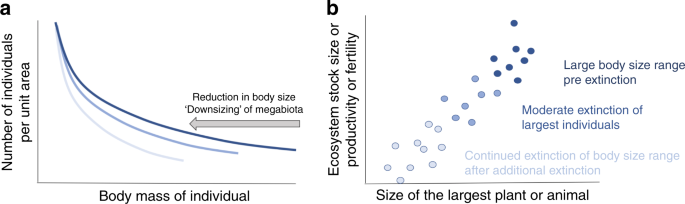

MST provides an analytical foundation to begin to understand the role of organismal size in ecology and evolution32. Building on previous work, we derive a baseline set of predictions that show that the largest body sized plants and animals have a disproportionate impact on ecological systems. Our extensions of MST to the ecology and evolution of the megabiota (See Supplementary Information) makes five general sets of predictions:

The megabiota have a higher risk of mortality and extinction

The megabiota are more prone to population reductions and extinction than smaller body sized species due to the compounding effects of habitat loss, human hunting and harvesting, and climate change (Fig. 1). Future climate projections show that terrestrial regions will be characterized by hotter and more pronounced droughts, and oceans and freshwater habitats will be characterized by warmer temperatures, decreased pH, and reduced oxygen concentrations25,38. These factors will place additional physical limits on plant and animal size, and reduce available habitat. As a result, rapid sudden climate change will negatively impact the growth and survivorship of larger trees (Fig. 1c), fish, and aquatic invertebrates leading to reductions in body sizes and potentially exacerbating feedbacks to climate change39 (Supplementary Information).

As we show in Supplementary Eqs. 4–5, Fig. 1a, b the probability of extinction, Eλ, in times of rapid climate change and/or exploitation and habitat loss, will scale positively with body size19. This is due to three key characteristics of the megabiota. First, they often operate closer to biophysical, physiological, and abiotic limits. So, the risk of mortality due to extreme events, R, is more pronounced in times of rapid climate change40. Second, as they have lower per capita fecundity rates, F41, their populations cannot rapidly rebound to change. Third, as a result, to maintain viable global population sizes, they require a larger minimum area, Am of habitat to avoid stochastic extinction42. Together, each of these characteristics scale with organism size, m, and combine to give a general allometric scaling expression for the probability of extinction, Eλ

$$E_lambda propto fleft[ {Rleft( {m^b} right) cdot 1/F(m^{ – c}) cdot A_m(m^d)} right]; propto ;m^{b + c + d}$$

(1)

We predict that during times of rapid habitat loss and climate change Eλ will scale positively with body size (see also ref. 43). Values of the scaling exponents are expected to approximate b ~ 1, d ~ 1, and c ≈ 0.25 so that (E_lambda propto m^{2.5}) (see Supplementary Information). Thus, as a rule of thumb, an organism that is 10 times larger in size will be about 316 times more susceptible to extinction during times of rapid change. Depending on the organism and environmental driver the values of b, d, and c will likely vary indicating that we expect this rule of thumb to vary. Nevertheless, compared to smaller body sized flora and fauna, in times of rapid climate change and reductions of geographic range, larger body-sized species face disproportionally increased risk of extinction19,44.

The findings of numerous recent studies are generally consistent with the above predictions. In times of rapid human land use and climate change, when compared to smaller flora and fauna, larger plants and animals face increased risk of mortality events8,19,38,43,44. Indeed, large trees are most susceptible to changing climate via warming temperatures and drought39. Compared to smaller trees, the biggest trees exhibit the greatest increases in mortality rate in hotter droughts relative to non-drought conditions39. An Amazon forest drought experiment has been simulating the impact of a moderate drought by reducing rainfall by a third in a 1-hectare forest plot45. In that experiment, tree mortality rates doubled for smaller trees but increased 4.5 times for the bigger canopy trees (Fig. 1). Similarly, the fossil record indicates that increasing drought and habitat fragmentation are associated with elevated extinction rates of larger mammals relative to those of smaller mammals19 (Fig. 1).

The megabiota disproportionately impact ecosystem stocks and total biomass

The megabiota disproportionately impact ecosystem functioning via influencing the scaling of total ecosystem standing stocks (e.g. the total amount of ecosystem carbon, nitrogen etc.; Fig. 2) and biomass (Supplementary Eqs. 6–9). This impact is the result of two important ecological factors—the size spectra (the distribution of the sizes of all plant or animal individuals found in a given location, Fig. 2a), and f, the allometric relationships that characterize how structural attributes and physiological/metabolic rates of an individual change or scale with differences in body size. Depending on the environment, plants and animals can fill and occupy space differently (three-dimensional packing of roots and canopies vs. more two-dimensional packing of animal home ranges and territories). As a result, the impacts of the megabiota can differ depending on their ecology.

In (a), for assemblages of either plants or animals, there is an inverse relationship between size and abundance. But, as larger organisms are disproportionately more prone to population reduction and extinction than smaller organisms, this leads to a reduction in the number of larger body sized individuals and a reduction in their numbers. As a result, past extinction and continued hunting, fishing, land and water use pressures in addition to climate change, are compressing body size distributions across most of the worldʼs ecosystems. In (b) metabolic scaling theory and empirical data show that communities and ecosystems with larger body sized plants and animals flux more energy and resources. As a result, continued reductions in body size in (a) will lead to a continued reduction in ecosystem stocks and flux of energy and nutrients.

In the case of terrestrial plants (autotrophs), the total biomass of the forest, MTot can be related by a primary size measure—the radius of the plant stem, r, and the size distribution of the stems in that forest, f(r) where (f(r) = cr^{ – eta }) (see Supplementary Eq. 7). The value of the exponent, η, may vary but is hypothesized to approximate (eta approx – 2) in undisturbed forests, a value supported by empirical studies46. Using idealized allometries, the total phytomass of an individual, m, can be related to the primary size measure—stem radius of a tree, r, where (mleft( r right) = c_m^{8/3}r^{8/3}), where cm is an allometric constant that may vary within or across taxa. We can then derive a general scaling law relating MTot and the size of the largest plant’s stem radius, rmax,

$$M_{mathrm{Tot}} = , {int} mleft( r right)fleft( r right){mathrm{dr}}, = {int} left( {frac{r}{{c_m}}} right)^{frac{8}{3}}left( {c_nr^{ – 2}} right)mathrm{d}r approx , left( {frac{3}{5}frac{{c_n}}{{c_m^{8/3}}}} right)r_{mathrm{max}}^{5/3}$$

(2)

As the trunk radius of the largest tree in the forest increases, the total forest biomass, Mtot, increases disproportionately faster. Specifically, total biomass increases as the size of the largest individual tree raised to the 5/3 or 1.67 power of its trunk radius, rmax. Expressed as a function of the mass of the largest tree in the forest, mmax (kg), the total forest biomass increases as the (M_{mathrm{Tot}} propto m_{mathrm{max}}^{5/8}) (Supplementary Information). So, the total amount of biomass contained within the forest increases as the 5/8 or 0.625 power of the mass of the largest tree in the forest.

Similarly, in the case of animals (applied to all individuals within a trophic level), the total biomass of a trophic group, MTot can be related by its primary size measure—organism biomass, m. The size frequency distribution of all animals is measured in terms of animal mass, f(m) where (f(m) = cm^{ – {it{epsilon }}}). The value of ({it{epsilon }}) may vary but is hypothesized to approximate ({it{epsilon }}) =−3/447. The total biomass of all animals in that trophic level, MTot is predicted to scale with the size of the largest animal, mmax (see Supplementary Information) as

$$M_{mathrm{Tot}} = , int mleft( m right)fleft( m right){mathrm{dm}} = int m cdot c_am^{ – 3/4}{mathrm{dm}} approx , frac{4}{5}c_nm_{mathrm{max}}^{5/4}$$

(3)

This predicted relationship, indicates that, in a given trophic level, as the mass of the largest animal increases, the total trophic biomass of all animals increases disproportionately faster. When expressed in terms of organismal biomass, this predicted superlinear scaling of total trophic biomass, shows that changes in maximum size of an animal mmax will have a larger and disproportionate impact on the total trophic biomass MTot (see Supplementary Fig. 1)

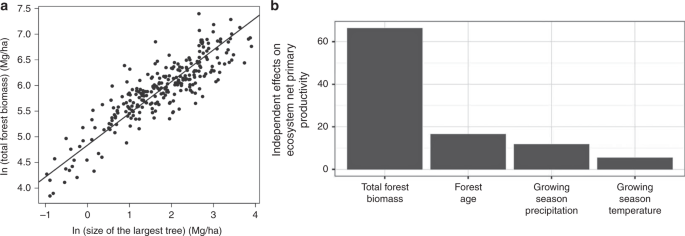

We tested these predictions via several different approaches. Observations of forests across the globe, in both temperate and tropical forest communities (Fig. 3) show that the size of the largest individual, mmax is a strong predictor of total forest biomass, MTot. The fitted scaling exponent for total forest biomass, 0.62 (95% CI = 0.58–0.66), is indistinguishable from the MST prediction of 5/8 = 0.625 (see ref. 48; Fig. 3). As we discuss below, global simulation models that incorporate metabolic and allometric scaling also show the predicted positive scaling relationship between body mass and total heterotrophic biomass (see below), but the relationship is modified by local climate.

In (a) the total above ground forest biomass is best predicted by the size of the largest tree. Analysis of biomass calculated from n = 267 independent forest plots distributed across the Americas from 40.7° S to 54.6° N latitude. The best single predictor of variation in forest biomass is the size of the largest tree in that forest. The fitted slope of the relationship (the scaling exponent) is 0.62, which is indistinguishable from the predicted scaling function from metabolic scaling theory where the total biomass should scale as maximum tree size to the 5/8 or 0.625 power. Data from ref. 48. In (b) global analyses of the relative importance of several drivers of variation in forest ecosystem net primary productivity (data from ref. 51). The most important driver of variation in terrestrial net primary productivity is the total forest biomass. Variation in forest biomass has a larger effect than precipitation, temperature, and forest age. As the best predictor of total forest biomass is the size of the largest individual (a) these results indicate that forests with large megaflora are more productive. Vegetation with megaflora collectively dominate the biomass and carbon stored in vegetation and the productivity of land vegetation.

The megabiota disproportionately impact ecosystem flows

MST predicts that the megabiota impact ecosystem functioning via their disproportionate impact on total trophic biomass which then drives the total metabolic and resource fluxes and ecosystem net primary productivity33. For autotrophs, the total energy flux through all plants, BTot and the total net biomass productivity or net primary productivity or NPP (or the total resource flux JTot) scales with the size of the largest individual and the total autotrophic biomass. In Supplementary Eqs. 10–13 we derive a general scaling law for how total trophic biomass, MTot, influences variation in ecosystem fluxes including total energy, BTot, biomass productivity, NPP, and carbon, and nutrients. The total resource utilization rate JTot (kg yr−1) of a given resource i, such as nitrogen, water, carbon etc, can be written as

$$J_{mathrm{Tot}} propto NPP propto B_{mathrm{Tot}} approx left( {tau kappa _i^{ – 1}B_0c_n} right)r_{mathrm{max}}$$

(4)

As the size of the largest tree within a forest increases, the total system flux will scale in direct proportion to the largest individual. The total amount of resources (carbon, water, nutrients) that pass through the ecosystem or through a food web will increase as maximum tree height increases. In terms of the total autotrophic biomass, as the size of the largest tree influences total forest biomass, MTot, (Eq. 2) and NPP, we can relate NPP to MTot as ({mathrm{NPP}} propto B_{mathrm{Tot}} approx b_0c_m^{8/5}c_n^{2/5}left[ {5/3M_{mathrm{Tot}}} right]^{3/5}). Thus, forests with trees 10 times larger in trunk diameter will store ~47 times more carbon (see above, Eq. 3) and will assimilate 10 times more carbon and produce 10 times more biomass. As a result, vegetation that contains larger individuals will disproportionately absorb and store more carbon and cycle more water and nutrients and in turn produce more biomass.

Similarly, for animals, because of the allometry of resource use and packing of ecological space, we have a similar but slightly different scaling relationship indicating that increases in the maximum body mass of an animal would also disproportionately increase the total amount of flux through the heterotrophic food web. With substitution, we then have

$$J_{mathrm{Tot}} approx left( {tau kappa _i^{ – 1}B_0c_nfrac{4}{5}c} right)m_{mathrm{max}}^{5/4}$$

(5)

Importantly, for animals, the flux of energy and matter through the heterotrophic food web is predicted to scale to the 5/4th or 1.25 power of the total heterotrophic biomass. Ecosystems with the largest animals 10 times larger in mass flux ~18 times more energy and nutrients (see above, Eq. 3). Thus, as the size of the largest individual (as measured by the primary size) within a given trophic group increases, the total ecosystem trophic flux will scale superlinearly.

Support for the above MST predictions are shown in Fig. 3, Supplementary Information, and by recent studies assessing the dynamical predictions for ecosystems46,49,50. Variation in forest biomass has a larger effect on variation in ecosystem productivity (NPP) than precipitation, temperature, and forest age51. Similarly, the best predictor of forest biomass is the size of the largest individual (Fig. 3a), together these results show that forests with large megaflora are more productive and contain more stored carbon (Fig. 3). For animals, tentative support for this prediction is given by earlier macroecological analyses where species of large body sized birds flux more energy than small body sized birds52.

The megabiota disproportionately impact ecosystem fertility

Larger herbivorous animals are disproportionately more important in the lateral movement of nutrients and energy in the biosphere via dung, urine and flesh. This movement takes two main forms: diffusion and directional transport. Recent work has utilized aspects of metabolic scaling theory to quantify the movement of nutrients across space by herbivores53. We show that MST makes specific predictions for the scaling of nutrient diffusivity in ecosystems as a function of the largest sized animal (“Methods”; Supplementary Information). Specifically, the diffusion of nutrients across the landscape by herbivores via defecation and urination, ϕ, scales positively with the size of the largest herbivore, mHerbivore.

$${phi} propto m_{mathrm{Herbivore}}^{1.17}$$

(6)

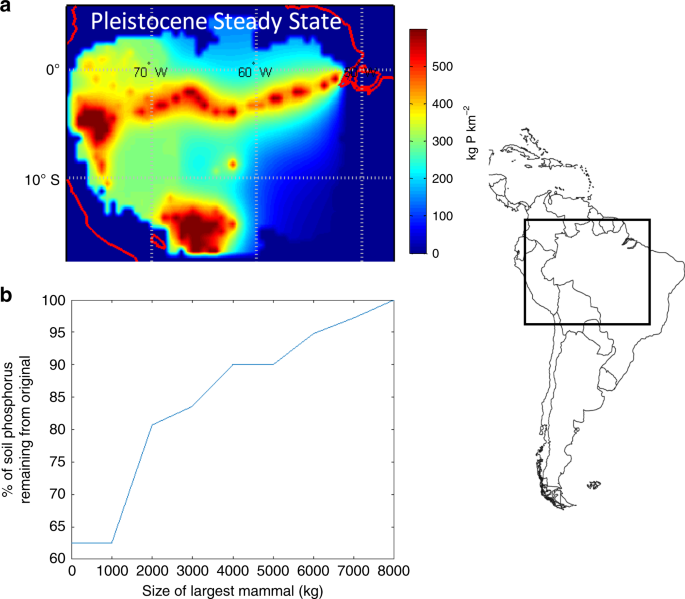

We assessed these predictions, by (i) simulating how a reduction in body size of herbivores in Amazonian forests affects the distribution of soil phosphorus across the Amazon basin (see the “Methods” section); and (ii) implementing the allometric scaling of metabolism and animal movement in a global simulation model (see below). Consistent with predictions, the Amazonian simulations show that the observed reduction in the size range of the megafauna in the Amazon from the Pleistocene baseline leads to reduction in ecosystem fertility as measured by steady state soil phosphorus concentrations (Fig. 4). Under a series of size thresholds for the extinct megafauna, we expect a 20–40% reduction in soil steady state P concentrations. Recent empirical studies are consistent with these predictions and point to the importance of megafauna on nutrient redistribution and fertilization of ecosystems54,55.

Predictions for how the steady state fertility of the Amazon basin (soil phosphorus concentrations) has changed in response to the megafaunal extinctions. This simulation is characterized by lateral diffusivity of nutrients, Φ, by mammals away from the Amazon river floodplain source. The diffusivity of nutrients through the Amazon via ingestion, transport, and eventual defecation yields a Φ value of 4.4 km2 yr−1 (based on Doughty et al.27). a Simulated steady state soil P concentrations across the Amazon Basin with the now extinct megafauna; b With the extinction of large mammals and a continued forecasted reduction in mammal body size, the percentage of original steady state P concentrations in the Amazon Basin will decrease. Here, under a series of size thresholds for the extinct megafauna, we expect a 20–40% reduction in soil steady state P concentrations. For instance, a 5000 kg size threshold removes all animals above 5000 kg and continental P concentrations are reduced by ~10%. A size threshold of 0 has all extant South American mammals. Amazonian map from MATLAB worldmap from the Global Optimization Toolbox, The MathWorks, Inc. www.mathworks.com.

Conservation implications of the multiplicative importance of the megabiota and total area protected

The megabiota are also disproportionately more impactful for conservation efforts prioritizing ecosystem functioning. For example, because the total biomass of a given trophic level, Mtot, will be directly proportional to the amount of area A (Mtot ~ A) protected56, doubling the area available for the megabiota will further have a disproportionate effect on ecosystem functioning (see Supplementary Eq. 16; Supplementary Fig. 1B). For example, efforts to maximize ecosystem services can be amplified by effort to maintain and increase large body sized plants and animals (Supplementary Fig. 1) and also conserve larger areas. Allowing for increases in maximum organism size and allowing more area to be restored to forest or to rewild large animals57 will together have a multiplicative and nonlinear effect on ecosystem services (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Global simulations of the biosphere with and without megaherbivores

One of the limitations of the above derivations from MST is that the analytical theory does not yet tackle the complexity of species interactions in differing landscapes. In particular, including how ecological interactions and dynamics within and across differing landscapes and trophic levels have yet to be detailed by MST. Removing the megabiota does more than just reduce the body size range of plants and animals—it changes how individuals and species interact with each other58. These networks of ecological interactions are also fundamentally altered by shifting the relative importance of competitive and mutualistic interactions and the presence of trophic cascades10. For example, loss of the megabiota could influence the growth and abundance of smaller plants and animals. Their response could then compensate for ecosystem functions and possibly negate the above predictions. To more fully assess how downsizing of the planet’s fauna will influence ecosystem processes within the context of complex species interaction networks we utilized a General Ecosystem Model (GEM).

We used the Madingley Model as it explicitly incorporates the importance of organismal body size (metabolic demands, foraging area, and population dynamics59; see Supplementary Fig. 2). This formulation of a GEM represents complex ecological interaction networks and whole-ecosystem dynamics at a global scale60. It is capable of modelling emergent ecosystem and biosphere structure and function by simulating a core set of biological and ecological processes for all terrestrial and marine organisms between 10 μg and 150,000 kg. Details of the simulation model are described in the methods section, Supplementary Information, supplementary Figs. 2–9).

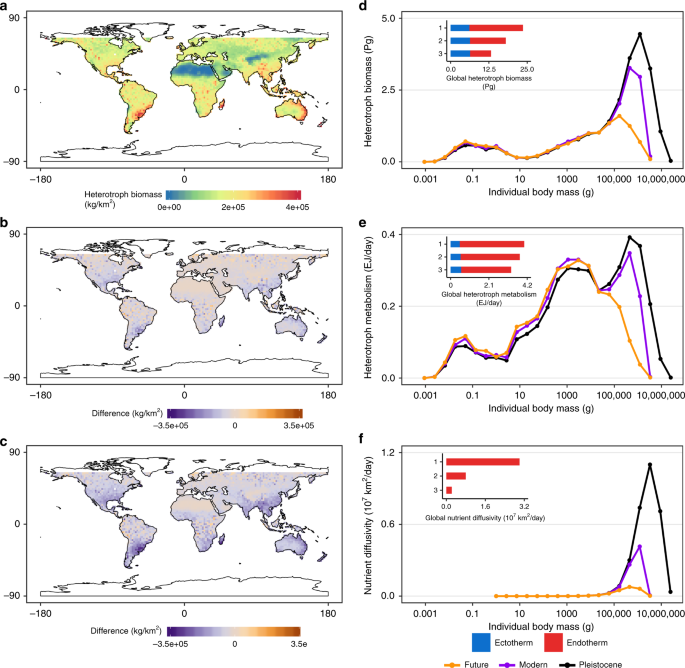

We generated a set of forecasts for how, since the Pleistocene, the downsizing of the terrestrial megafauna has altered or will alter the functioning of ecosystems and biosphere. We ran three sets of simulations, or three different worlds (see “Methods” and Supplementary Information). In each world, we simulated the loss of the endotherm herbivore megafauna by experimentally changing the maximum attainable body mass. Each world differed in maximum size by an order of magnitude, from 10,000 kg (the largest terrestrial Pleistocene herbivore, Mammuthus columbi), to 1000 kg (typical modern day maximum size of terrestrial mammalian taxa) and finally 100 kg (a future world lacking wild megaherbivores). The body mass ranges for all other terrestrial animal cohorts were held constant and approximating those found in the Pleistocene fossil record (see ref. 60; Table 1; see Supplementary Fig. 2). We hereafter refer to these three worlds as (i) Pleistocene world, (ii) Modern world; and (iii) Future world.

Multiple lines of evidence from the GEM simulations (Fig. 5a–c) are consistent with predictions from MST (Eqs. 2–6; see also Supplementary Eqs. 9, 11, 13–15). We observed a disproportionate impact of the megabiota with a positive, but increasing, relationship with maximum body size and ecosystem function (Fig. 5d–f),. Reductions in the size of the largest animal—megaherbivores—leads to a decrease in biosphere functioning (Table 1; Fig. 5d–f). Compared to the Pleistocene baseline, the total biosphere biomass is predicted to decrease 44.1% from 23.60 Pg to 13.20 Pg (Fig. 5d, Table 1). The impacts of megaherbivore loss vary spatially indicating that local climate and species composition may further modify MST predictions. Large impacts of megaherbivore loss are observed in sub-tropical regions of the world (see Supplementary Figs. 4,8–9) because these regions are characterized by the largest animals (see Supplementary Fig. 4c, e). Reductions in maximum herbivore body size have the greatest impact on ecosystem nutrient diffusivity, with global measures of future nutrient diffusivity decreasing by 92.4% between the Pleistocene and Future worlds (Fig. 5f, Table 1). The loss of megaherbivores in a future world has a smaller impact on global heterotrophic metabolism (decreasing 18%; see Table 1).

The annual mean heterotrophic community biomass from three ensemble experiments using the General Ecosystem Model (GEM) mapped spatially showing a the Pleistocene world, b the difference between the Pleistocene world and Modern world and c Future world. The implications of this downsizing for the functioning of the biosphere are measured using the annual mean of the GEM experiments for the three ecosystem-level measures; d heterotrophic biomass, e heterotrophic metabolism and f nutrient diffusivity summarized into 25 mass bins. The inset graphs display the global total for each metric and are numbered (1) Pleistocene, (2) Modern and (3) Future world respectively. Global map from the 110 m land polygon shapefile from Natural Earth Data (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/110m-physical-vectors/).

We also tested an important alternative hypothesis—with the loss of the megabiota, the response of smaller organisms could compensate for the loss of the megabiota. Specifically, with the loss of ecological interactions from the megabiota, ecological and evolutionary responses from smaller organisms could lead to changes in their abundance and range61 and compensate for the loss of large herbivores and carnivores. We used the GEM to test if smaller animals experience an ecological release with the loss of the larger body plants and animals, and if they can they provide the ecosystem functions of the megabiota. Our results indicate that while there is some compensation from the smaller organisms in terms of heterotrophic metabolism (Fig. 5e), we see little to no compensation in global heterotrophic biomass and nutrient diffusivity (Fig. 5d, f).

Source: Ecology - nature.com