We performed an experiment in which a parental generation of Japanese quails were fed with either GBH-contaminated food (N = 13 breeding pairs) or control food (N = 13 breeding pairs) from the age of 10 days to 12 months, and eggs and embryos from these pairs were collected. Details of the experimental design and parental exposures are described in42.

The GBH-exposed parents were fed organic food (Organic food for laying poultry, “Luonnon Punaheltta” Danish Agro, Denmark) with added commercial GBH (RoundUp Flex 480 g/l glyphosate, present as 588 g/l [43.8% w.w] of potassium salt of glyphosate, with surfactants alkylpolyglycoside (5% of weight) and nitrotryl (1% of weight) (AXGD42311 5/7/2017, Monsanto, 2002). The control parents were fed the same organic food in which water was added without GBH. A GBH product was selected over pure glyphosate to mimic the exposures in natural environments including exposure to adjuvants, as adjuvants may increase the toxicity of glyphosate2,43. However, with this experimental design we could not distinguish the potential effects of adjuvants themselves, or whether they altered the effects of the active ingredient, glyphosate. The concentration of glyphosate in the GBH food was aimed at ca 200 mg/kg food, which corresponds to a dose of 12–20 mg glyphosate/kg body mass/day in full-grown Japanese quails. Eason and Swanlon44 estimated that up to 350 mg/kg glyphosate could end up in grains when GBHs are spread on the fields before harvesting. However, the based on actual measurements, European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)45 estimated for poultry a maximum of 33.4 mg/kg glyphosate in feed (dry matter), corresponding to maximum intake of 2.28 mg/kg body mass daily. EFSA further reports a NOAEL (No Adverse Effects Level) of 100 mg/kg body mass/day for poultry45; therefore, our experiment tests a rather moderate concentration well below this threshold, yet above the estimated maximum residue by EFSA. Furthermore, a dose of 347 mg/kg did not negatively influence adult body mass in Japanese quails in a short-term experiment44. According to the manufacturer, acute toxicity (LC50) (via food) of RoundUp Flex is >4640 mg/kg food for mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) and bobwhite quail (Colinus virginianus).

GBH food was prepared every week to avoid potential changes in concentration caused by degradation. Diluted RoundUp Flex was mixed with the organic food in a cement mill (Euro-Mix 125, Lescha, Germany). The food was air-dried and further crushed with a food crusher (Model ETM, Vercella Giuseppe, Italy) to a grain size suitable for the birds considering their age. The control food was prepared using a similar method, but only water was added to the food and a separate cement mill was used (ABM P135 L, Lescha, Germany). After crushing, the dry food was stored in closed containers at 20 °C in dry conditions. Separate equipment for food preparation and storage were used for GBH and control food to avoid contamination.

To verify the treatment levels in the parental generation, glyphosate concentration was measured in 6 batches of food and residue levels were measured in excreta (feces and urine combined) samples after 12 months of exposure. The average glyphosate concentration of 6 batches of food was 164 mg/kg (S.E. ± 55 mg/kg). The average glyphosate concentration in 3 pools of excreta samples (urine and fecal matter combined) was 199 mg/kg (S.E. ± 10.5 mg/kg). The control feed and control pools of excreta were free of glyphosate residues (<0.01 mg/kg).

Egg mass

Parental generation was reared in same-sex groups for the first 12 weeks and thereafter in randomly allocated female-male pairs of the same treatment. Eggs were collected for measurements of egg mass when the birds were 4 and 12 months old. Eggs from each cage were collected eggs daily (quails generally lay one egg per day), marked individually, and weighed. A total of 221 and 96 eggs were collected at 4 and 12 months, respectively.

Egg quality: Yolk and shell mass and thyroid hormones

Additional 24 unincubated eggs (N = 12 per group) were collected at 4 moths of exposure for egg component analyses. Eggs were thawed and the yolk and shell were separated and weighed (accuracy 1 mg). T3 and T4 were measured from yolk following previously published methods46 and were expressed as pg/mg yolk.

Egg glyphosate residue analysis

When the birds were 10 months old, eggs from each cage were collected daily for 1 week, marked individually, and frozen at -20 °C for glyphosate residue analysis. Prior to analysis, randomly selected 5 eggs (originating from 5 different females) from both the GBH and control treatments were thawed and the shells carefully removed. To avoid contamination, all eggs were processed in a lab that was never in contact with glyphosate, using clean materials (gloves, petri dishes, tubes) for each egg. When removing content from the eggshell, the egg content was never in touch with the outer egg shell. The contents of 5 eggs from the control treatment were then pooled for glyphosate residue analysis. Pooling was done to reduce the costs of glyphosate analyses. The contents of 5 eggs from the GBH treatment were individually analysed for glyphosate residues.

Development and tissue sampling

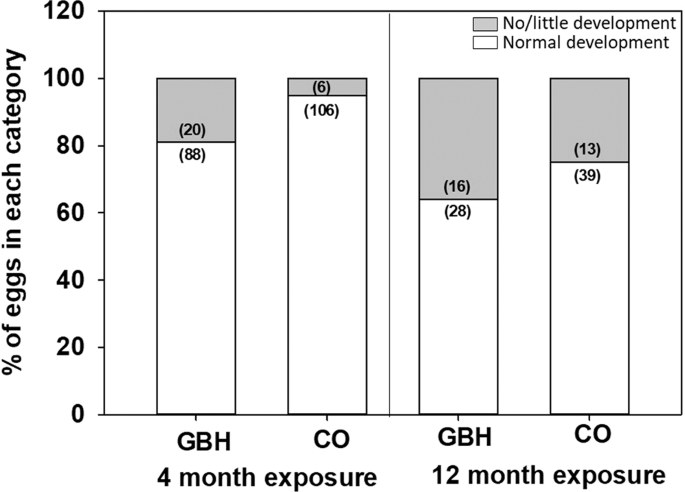

Embryo development was assessed after 4 and 12 months of parental exposure to GBHs. At 4 months, 108 GBH and 112 control eggs (see ‘egg mass’) were artificially incubated for 3 days at 36.8 °C and 55% humidity (Rcom Maru Max, Standard CT-190, Autoelex CO. LTD, South-Korea). Eggs were thereafter chilled and assessed for the presence of a normally developed embryo (coded 1) or no embryo/a very small embryo (coded 0) by naked eye. Note that by naked eye, one cannot distinguish between the unfertilized eggs and an embryo that died very early – yet the key idea was to study whether eggs developed to normal 3d-embryos or not to assess the effects of GBHs on development and reproduction.

After parental exposure for 12 months, 44 GBH and 52 control eggs were collected fresh and incubated for 10 days (i.e. 55% of the normal embryonic developmental period, 17 to 18 days) to assess general development (again, coded as 1 for normal development and 0 for no embryo/a very small embryo). The whole brain tissue of the embryo was dissected, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and later stored at −80 °C for oxidative biomarker analysis.

The experiments were conducted under licenses from the Animal Experiment Board of the Administrative Agency of South Finland (ESAVI/7225/04.10.07/2017). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (Act on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes, 497/2013).

Brain mass and oxidative status biomarkers

We aimed to analyze 2 randomly selected embryo samples per breeding pair (N = 13 pairs/treatment). However, as not all females were producing eggs, or did not produce eggs with (viable) embryos, the final sample size was 19 control embryos (from 10 females) and 16 GBH embryos (from 10 females). Brain homogenates were used to measure oxidative status biomarkers, antioxidant enzymes glutathione-S-transferase (GST), glutathione peroxidases (GPx), catalase (CAT), and oxidative damage to lipids (malonaldehyde, MDA as a proxy, using TBARS assay). Whole brains were weighed (~0.1 mg) and homogenized (TissueLyser, Qiagen, Austin, USA) with 200–400 µl KF buffer (0.1 M K2HPO4 + 0.15 M KCl, pH 7.4). All biomarkers were measured in triplicate (intra-assay coefficient of variability [CV] < 15% in all cases) using an EnVision microplate reader (PerkinElmer, Finland) and calibrated to the protein concentration in the sample following47. The GPx-assay (Sigma CGP1) was adjusted from a cuvette to a 384-well plate. GPx was measured following kit instructions but instead of t-Bu-OOH, we used 2 mM H2O2, which is a substrate for GPx and CAT. To block CAT, 1 mM NaN3 was added and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 with the HCl in the buffer provided with the kit48,49. GST-assay (Sigma CS0410) was likewise adjusted from a 96- to a 384-well plate using our own reagents: Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline–buffer (DPBS), 200 mM GSH (Sigma G4251), and 100 mM 1-Chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) (Sigma C6396) in ethanol, see details in50. The CAT-assay (Sigma CAT100) was adjusted from a cuvette to a 96-well plate. We used a 0.3 mg/ml sample dilution, see details in48,51. The lipid peroxidation was analyzed using a 384-plate modification of a TBARS-assay following52.

Statistical analysis

Egg mass was analyzed using linear mixed models (LMMs) with treatment (GBH or control), exposure duration (4 or 12 months) and their interaction as predictors, female mass as a covariate, and breeding pair ID as a random effect to control for non-independence of eggs from the same pair.

$${rm{Egg}},{rm{mass}}={rm{Treatment}},ast ,{rm{Period}}+{rm{Female}},{rm{mass}},({rm{covariate}})+{rm{Pair}},{rm{ID}},({rm{random}})$$

(1)

Differences between the GBH and control groups in yolk and eggshell mass and egg thyroid hormone levels were analyzed with two-sample t-tests. The likelihood of embryo development was analyzed using generalized linear mixed models (binomial distribution, logit link):

$${rm{Development}}={rm{Treatment}},ast ,{rm{Period}}+{rm{Female}},{rm{mass}},({rm{covariate}})+{rm{Pair}},{rm{ID}},({rm{random}})$$

(2)

Embryo brain mass, GST, GP, CAT, and MDA were analyzed using LMMs as following:

$${rm{Response}}={rm{Treatment}}+{rm{Pair}},{rm{ID}},({rm{random}})+{rm{Assay}},{rm{ID}},({rm{random}})$$

(3)

The Kenward-Rogers method was used to estimate the degrees of freedom. Residuals of the models were visually inspected to confirm normality and heteroscedasticity. All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1. All data are available as Supplementary Data Files (1–3).

Source: Ecology - nature.com