Preservation

The specimen has severely been compacted to about 7 mm of total thickness. As a result, boundaries between bones are often unclear in CT images when a bone is preserved on top of another. Unlike the right side of the skull that is articulated, the left side, which was hidden previously and revealed by CT scanning for the first time, is disarticulated, although many bones are still located close to the original positions. Thus, it is likely that the specimen was deposited with the right side facing down and embedded in sediment, while the left side was exposed for longer and became disarticulated. Some posterior cranial bones are missing, including large parts of the left angular and surangular and most of the occiput. One possible mandibular element, tentatively identified as a possible prearticular in Fig. 2b, is found postcranially, overlapping the right clavicle, suggesting disturbance of the left-posterior part of the skull before complete burial.

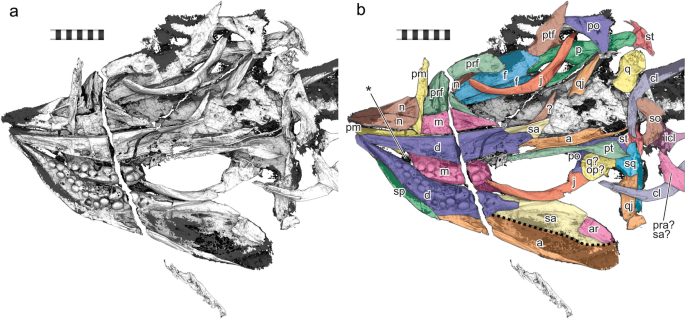

3D rendering of the hidden side of the holotype of Cartorhynchus lenticarpus (AGB 6257), revealing the dentition. (a) Volume rendering using 2d transfer function on the CT slices. (b) Surface mesh rendering based on Sequential Isosurface Trimming (see Methods). (c) Same as b with some cranial bones identified. Abbreviations: a angular; ar, articular; cl, clavicle; co, coronoid; d, dentary; f, frontal; icl, interclavicle; j, jugal; m, maxilla; n, nasal; p, parietal; pm, premaxilla; po, postorbital; pra, prearticular; prf, prefrontal; ptf, postfrontal; q, quadrate; qj, quadratojugal; sa, surangular; so, supraoccipital; sp, splenial; sq, squamosal; st, supratemporal. Scale bar in 1 cm.

Tooth orientation and ‘occlusion’

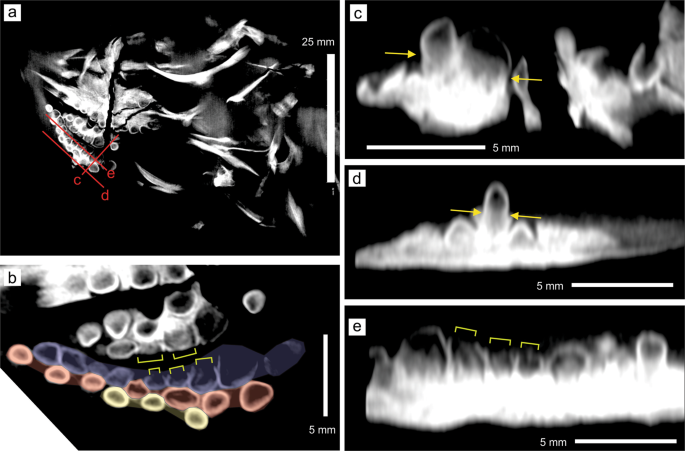

The most unusual feature of the dentition is the orientation of the teeth. Unlike in most vertebrates, many teeth are perpendicular to the outer walls of the respective jaw rami, especially posteriorly (Fig. 3), and therefore completely concealed when viewing the ramus perpendicularly from its outer side. The tooth orientation in natural posture is more horizontal than vertical (Fig. 3), when it is nearly vertical in most reptiles. The outer walls of the jaw rami are preserved parallel to the bedding plane, with the teeth approximately vertical to the plane, i.e., compactional bias is unlikely to alter the orientation of the teeth (see Discussion).

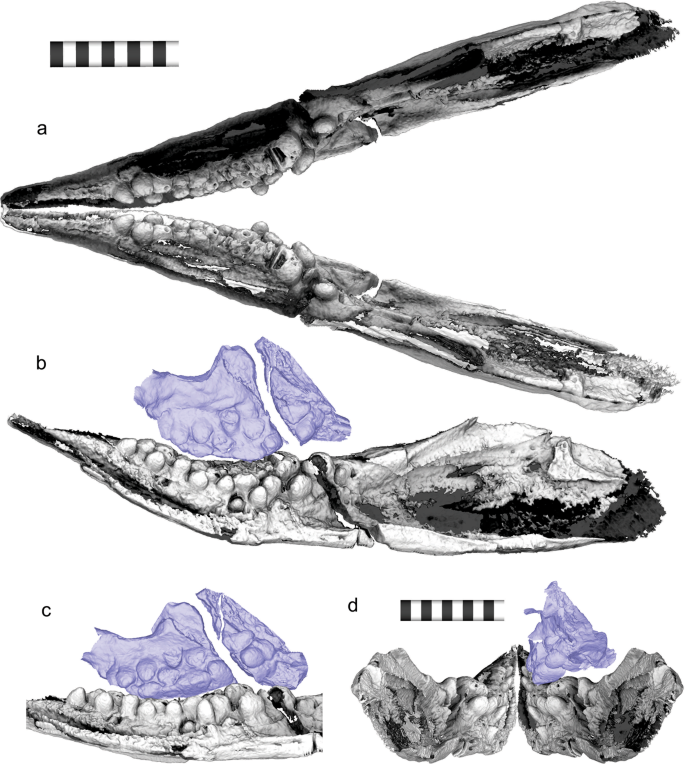

3D Reconstruction of mandibular posture. (a) Dorsal view of the reconstructed mandible. (b) Medial view of the reconstructed mandible and maxilla. (c) Medio-ventral view of the dentary and maxillary ‘occlusion’. (d) Same from posterior view. Maxilla is colored in purple. Scale bar is 1 cm.

The most-likely inclination of the mandibular rami is presented in Fig. 3 (see Methods). Because of the peculiar tooth orientation, the maxillary and dentary teeth do not contact each other tip to tip, and instead, ‘occlusion’ occurs between the side walls of the tooth crowns of the maxilla and dentary (see Discussion). This strange ‘occlusion’ is also evidenced by the tooth wear. Both maxillary and dentary teeth have been worn from their sides facing the corresponding dentition, and the worn maxillary dentition seems to fit into a shallow basin of worn dentary teeth (Fig. 3b–d). The worn teeth lack the thin wall of dense material on the occlusal side, which had most likely been worn through ‘occlusion’ (yellow brackets in Fig. 4b,e). The tooth wear is not an artifact of preservational compaction because the teeth outside of the occlusal area are not worn. The upper and lower teeth do not abut against each other in their preserved postures, so the wear was formed before the burial.

Sectional images of the 3D volume based on the CT images. (a) Section through the head region approximately parallel to the bedding plane. (b) A close-up view of the right dentary (below) and maxillary (middle to above) dentition in a, with a part of the left dentary teeth along the top margin. Dentary tooth rows are colored, with the labial row in blue, middle row in red, and lingual row in yellow. (c) A cross-section through the red line labeled c in a, nearly parallel to the longitudinal direction of the dentary teeth. (d) A cross-section through the red line labeled d in a, nearly parallel to the longitudinal direction of the dentary teeth. (e) A cross-section through the red line labeled e in a, nearly parallel to the longitudinal direction of the dentary teeth. Yellow allows point to the constriction between the crown and root. Yellow square brackets indicate the parts of tooth crowns without the enamel due to tooth wear.

Tooth morphology and arrangements

A total of 21 teeth are recognized on the right dentary, forming three rows that are approximately parallel to the jaw margin. There are 10, 7, and 4 teeth, respectively, in the labial, middle, and lingual rows (Fig. 4b; note that two immature teeth are not showing in this cross section, namely the most posterior tooth of the labial row and the second to the last tooth of the lingual row). The left dentary has 10, 7, and 3 teeth in the labial, middle, and lingual rows, respectively, but the count is less accurate given that they are not exposed on either side of the specimen. The antepenultimate tooth of the labial row of the right dentary is the largest, with the maximum crown diameter of 3.13 mm along the horizontal plane and a crown height of 1.65 mm, as measured from CT slices. The teeth in the more labial row are on average larger than those in the more lingual row, although the difference is minor when excluding the antepenultimate tooth of the labial row. The anterior part of the dentary, approximately corresponding to the premaxilla in the upper jaw, is edentulous.

The right maxilla has 12 teeth in two rows, and a tooth position belonging to the third row. Seven of the teeth are in the labial row and 5 in the middle row. The third-row tooth position is located lingual to the middle row and houses a partly formed tooth crown that is much smaller than the space and tilted about 90 degrees relative to other tooth crowns. The hidden left maxilla seems to have at least 7 and 3 teeth, respectively, in the labial and middle rows, and again there seems to be a single tooth in the lingual row.

The tooth crowns are generally rounded, with the crown apex shape ranging from weakly pointed to completely flattened (Figs. 2 and 4c–e), from anterior to posterior and from lingual to labial within the dentition. Most tooth crowns have disto-mesially elongated cross-sectional shapes, except for a few posterior teeth along the jaw margin that are as wide as long in cross-section. All tooth crowns are swollen at least to some extent (Fig. 4c–e), unlike in more derived ichthyosauriforms where molariform teeth are exclusively found in heterodont dentitions with conical anterior and molariform posterior teeth. Cross-sectional images also reveal that the tooth crowns are unusually thin-walled, as judged by the distribution of dense material that at least contains the enamel (Fig. 4a–e). However, the CT images do not allow clear separation of the dentine from the enamel and the rock matrix, which may have high density depending on the place probably because of concretion. Also, the gray levels in the images seem to be driven by artifacts, such as beam hardening and scattering than the actual density of the material, especially near the boundary of bones and teeth. For example, inside the dense wall, the teeth in Fig. 4c–e are least dense (i.e., dark) near the crown apex and becomes denser toward the bottom but this change unlikely to reflect biological structures. Also, the distributions of the darkest parts are inconsistent across images (compare Fig. 4c with e). Thus, the “wall” in the current context means the periphery of the teeth with high density. The root is present in most teeth. Many of the teeth are constricted between the root and crown, even in the largest teeth in the postero-labial region (yellow arrows in Fig. 4). The root is approximately cylindrical without any fluting or infoldings that are typically found in ichthyopterygians.

The dentigerous region is 18.9 mm long in the right dentary and 14.3 mm in the right maxilla. Thus, some dentary teeth have no corresponding teeth in the upper jaw. These teeth are found in the most anterior part of the dentary dentition, where the gap between the right and left mandibular rami is narrow. See Discussion.

Relative tooth size and crown shape index

Massare (1987) proposed a combination of two tooth characteristics to divide the feeding guilds of Jurassic and Cretaceous marine reptiles, namely the crown shape index quantified as the ratio between the height and diameter of the largest tooth crown in the dentition, and the relative tooth size, measured as the maximum dimension of the largest tooth crown to the skull width12. These two metrics were estimated for the present specimen.

The estimation of the tooth size index involves the skull width, which is ideally measured between the quadrates but may be substituted by the width between the lateral sides of the supratemporals in ichthyosauriforms, where the two values are usually similar to each other. Unfortunately, one each of the quadrate and supratemporal has been displaced, making direct measurements of the skull width unreliable. However, a half of the skull width can be measured on the right side of the skull roof that retains its articulation, providing a value of 15.1 mm between the lateral margin of the supratemporal and the sagittal line, measured perpendicular to the latter. This results in an estimated skull width of 30.2 mm.

The crown shape index based on the largest dentary tooth is 1.90, placing Cartorhynchus in the crushing guild characterized by an index value above 1.0. The relative tooth size is about 0.104, again placing Cartorhynchus in the crushing guild, characterized by values equal to or greater than 0.1.

Jaw symphysis

The tooth orientation and size, together with the morphology of the anterior tip of the dentary, make it difficult for the right and left mandibular rami to form a solid symphysis. The teeth occupy much of the medial surface of the mandible anteriorly, leaving only the very tip of the snout for possible symphyseal articulation. Yet, the rostral tip of the mandible is slender and curved upward, without a symphyseal surface on the medial side. Therefore, the jaw symphysis, if any, was weak. The jaw symphysis is also weak in Hupehsuchia13, the sister taxon of Ichthyosauriformes, so the weakness in C. lenticarpus is phylogenetically reasonable.

Cranial morphology

The CT imaging illuminated misidentifications of bone sutures and one misinterpretation of morphology in the original description8. The parietal seems to have the parietal ridge and slope14 based on the CT images. The premaxilla has a short supranasal process that forms the anterior-dorsal margin of the external naris. Also, the right quadrate, which was thought to underlie the right quadratojugal, seems to have been dislocated, and most of what was identified as the quadrate is parts of the quadratojugal and squamosal.

Ancestral state reconstruction

Ancestral state reconstruction based on likelihood suggests that common ancestors along the main lineage of Ichthyosauriformes likely retained conical teeth, and that rounded teeth most likely evolved five times in ichthyosauriforms (Fig. 1a). The parsimony reconstruction suggests that molariform teeth evolved three to five times in ichthyosauriforms, and that the common ancestors along the main lineage of Ichthyopterygia unambiguously retained conical teeth (Fig. 1b).

Source: Ecology - nature.com