Characterization and reproduction of Ionopsis utricularioides colours

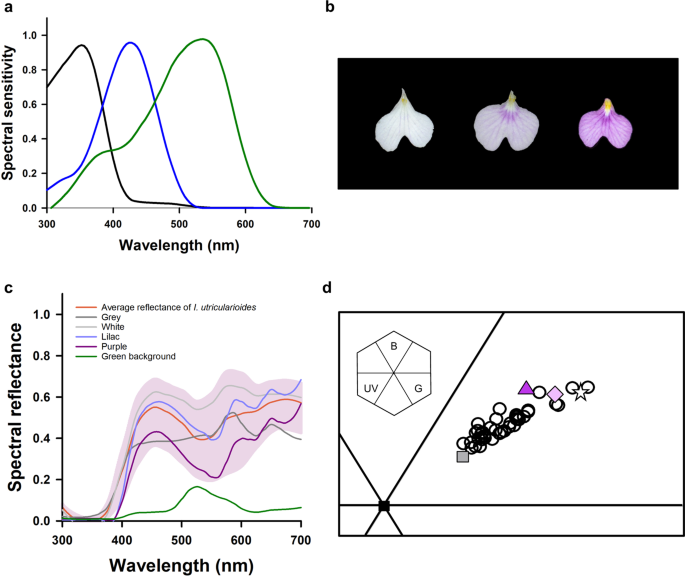

We measured the spectral reflectance of the orchid flowers (see Methods for details) and calculated the loci of the colours measured in the colour hexagon, a generalized colour-opponent model proposed for hymenopterans19. As no electrophysiological measurements exist for the spectral photoreceptors of Scaptotrigona aff. depilis, we used those of another Meliponini as an appropriate choice in the light of the similarity found between the spectral sensitivity curves characterized for various bee species20 (Fig. 1a).

Colour analysis. (a) Spectral sensitivity curves of the three photoreceptor types of the stingless bee Melipona quadrifasciata. (b) Lips of Ionopsis utricularioides showing the continuous variation from white to purple for the human eye. (c) Spectral reflectance curves of the orchid flowers (the pink area represents the range between the max and min natural reflection curves; the red line represents the mean reflection), the artificial colours (grey, white, lilac and purple) and of the green background used in the experiments. (d) Loci of the natural and artificial colour stimuli in the colour hexagon, a generalized colour space for hymenopterans. Each open circle represents an individual orchid (n = 40). The other symbols correspond to the artificial colours (triangle: purple, diamond: lilac, star: white, square: grey). The inset shows the hexagon and its sections defined based on opponent processing of photoreceptor signals (B: blue; G: green; UV: ultraviolet).

The flowers of I. utricularioides varied from white to purple to the human eye (Fig. 1b) and did not reflect in the range of ultraviolet (300–350 nm; Fig. 1c). They occupied the blue-green area of the colour hexagon (Fig. 1d). and presented a continuous floral colour polymorphism, where the more distant points in that space were separated by distances larger than 0.1 hexagon units (HU), which corresponds approximately to a discrimination level of 60% in bees21. Intermediate colour loci were separated from each other by distances smaller than 0.1 HU, thus suggesting a difficulty to discriminate them22,23. Flower colours varied between individual plants, but all flowers from the same plant presented the same colour.

Using the information obtained from the spectral reflectance measurements, we produced three colours similar to the ones displayed by the orchids using a colour printer (see Methods for details). The colours appeared white, lilac and purple to the human eye (Fig. 1c, Table 1). Furthermore, a grey colour was also printed to act as a “neutral stimulus” associated with food reward.

Figure 1c,d shows that the printed colours fell within the natural range of I. utricularioides colours and were highly similar to them both in their spectral reflectance and in their loci in the hexagon space. Compared to the chromatic stimuli, the grey stimulus was closer to the centre of the hexagon, i.e. closer to the achromatic region of that space (Table 1). Figure 1c shows in addition the spectral reflectance curve of the green background on which the artificial flowers were presented.

Colour choices in a non-rewarding, discrete polymorphic scenario

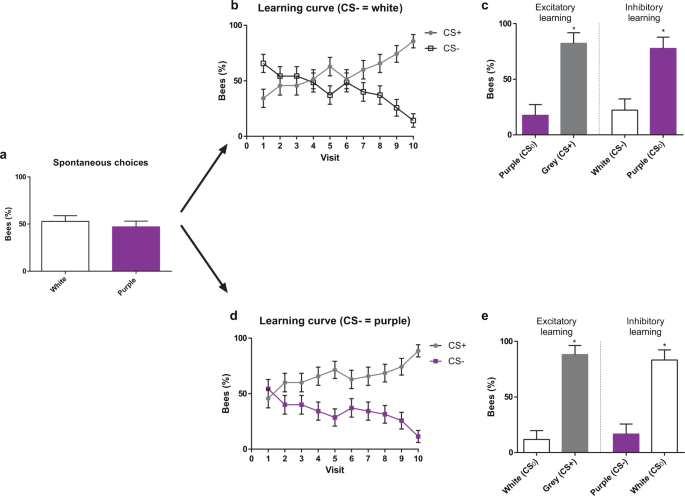

The experiment started with a spontaneous-preference test, in which each individually marked Scaptotrigona bee was presented with two non-rewarding artificial flowers, each displaying a different colour, white or purple. A single choice was recorded per bee. No significant preference was found between these two colours (Fig. 2a; white = 52.85%, purple = 47.14%, χ2 = 0.4566, df = 1, P = 0.4992; n = 70).

Colour choices in a non-rewarding, discrete polymorphic scenario. (a) Spontaneous choice of a white and a purple flower presented simultaneously. (b) Acquisition curves of bees trained along ten consecutive visits with three rewarded grey flowers (CS+) vs. three non-rewarded white flowers (CS−). (c) Tests opposing grey (CS+) to purple (CS0) (left) and white (CS−) to purple (CS0) (right). Bees preferred the CS+ over the CS0 and the CS0 over the CS−. (d) Acquisition curves of bees trained along ten consecutive visits with three rewarded grey flowers (CS+) vs. three non-rewarded purple flowers (CS−). (e) Tests opposing grey (CS+) to white (CS0) (left) and purple (CS−) to white (CS0) (right). Bees preferred the CS+ over the CS0, and the CS0 over the CS−. *: P < 0.05. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.).

After this test, each bee was trained to forage on a patch of six artificial flowers, three of which displayed the grey colour (CS+) and were rewarded with 50% (w/w) sucrose solution, while the other three displayed either the white or the purple colour (CS−) and were non-rewarded. Two groups were trained: one in which the CS− was white (n = 35) and another in which it was purple (n = 35).The chromatic contrast between the CS+ and CS− colours was higher in the case of grey vs. purple (0.1921 HU) than in grey vs. white (0.1032 HU; see Table 1). Each rewarded flower provided 300 µl of sucrose solution, which suffices to fill the crop of a foraging bee; non-rewarded flowers provided the same volume of water.

Each bee was recorded during 10 consecutive flower choices. If a bee landed on a non-rewarded flower, white or purple, it moved to a next flower until finding the sucrose reward. If it landed on the grey flower, it found the sucrose solution and stayed there until filling its crop, returning afterwards to the hive. For each of the ten visits recorded, we computed the % of bees having chosen either the CS+ or the CS− flowers. Learning would be visible by a progressive increase of the % of bees visiting the grey flowers along the ten visits recorded.

Figure 2b,d shows the learning curves of the two groups of bees trained to choose the grey CS+ colour vs. their respective CS− colour, white or purple. Although the CS+ and the CS− curves mirror each other given the way in which performance was computed (a bee choosing a CS+ flower did not choose a CS− flower, see above), we presented both curves to provide a comparative view of how both groups of bees learned the discrimination. In both cases, the proportion of bees choosing correctly the grey rewarding flowers during the ten foraging bouts increased, decreasing thereby the choice of white / purple non-rewarding flowers (CS− white, χ2 = 31.252, df = 9, P < 0.01, n = 35; CS− purple, χ2 = 28.195, df = 9, P < 0.01, n = 35). In the last two visits, practically all the bees were going exclusively and directly to a grey flower, ignoring the CS− flowers. No significant differences were found in discrimination success between the two groups of bees (df = 9, χ2 = 8.1152, P = 0.522), which indicates that differences in chromatic contrast between the CS+ and the CS− colours did not influence discrimination learning.

After the tenth floral choice, all six flowers were removed and a test with two non-rewarded flowers was performed. Each group of bees was split in two subgroups to perform a single test per subgroup. During a test, a single choice was recorded per bee. In one test, one of the flowers presented the grey colour (CS+) and the other flower a novel colour (CS0), which was, in fact, the CS− of the alternative group of bees (i.e. purple for bees trained with grey vs. white, and white for bees trained with grey vs. purple). This test allowed to evaluate if, as expected, bees preferred the grey colour to the novel CS0 colour based on the excitatory properties of the CS+. The other test confronted the CS− colour (white or purple, depending on the experimental group) to the CS0 colour (purple or white, respectively). This test represents an approximation to a deceptive, discrete polymorphic scenario: the two colours were both non-rewarding and well distinguishable from each other. The test allowed evaluating if besides learning to choose the grey CS+ colour, bees also learned to avoid their CS− colour based on its inhibitory properties, and thus preferred to visit the novel CS0 colour.

In the test confronting the grey colour to the novel colour (Fig. 2c,e, ‘Excitatory learning’), bees preferred significantly the grey colour, which had been associated with food reward (CS− white: grey = 82.35%, purple = 17.64%; χ2 = 11.725, df = 1, P < 0.01, n = 17; CS− purple: grey = 88.23%, white = 11.76%; χ2 = 14.328, df = 1, P < 0.01, n = 17). This result shows that bees were guided by the positive expectations induced by the rewarding grey colour during training.

In the test confronting the CS− colour to the CS0 colour (Fig. 2c,e, ‘Inhibitory learning’), bees always preferred the novel colour to the non-rewarded colour (Figs. CS− white: white = 22.22%, purple = 77.77%, χ2 = 9.765, df = 1, P < 0.001, n = 18; CS− purple: purple = 16.66%, white = 83.33%, χ2 = 12.951, df = 1, P < 0.001, n = 18). This preference reveals that during the training, they learned the inhibitory properties of the CS−, which led them to avoid actively this stimulus and to choose the distinct novel stimuli during the test.

The latter result thus provides important insights to understand some aspects of a deceptive discrete polymorphic scenario. A foraging bee, driven by appetitive expectations, and having experienced a negative outcome at a coloured morph of a polymorphic orchid, will afterwards avoid that negative colour and prefer another morph displaying a distinct, discriminable colour. Colour variability thus further promotes visits to orchid flowers based on the learning of appetitive and aversive experiences during foraging.

Colour choices in a non-rewarding, continuous polymorphic scenario

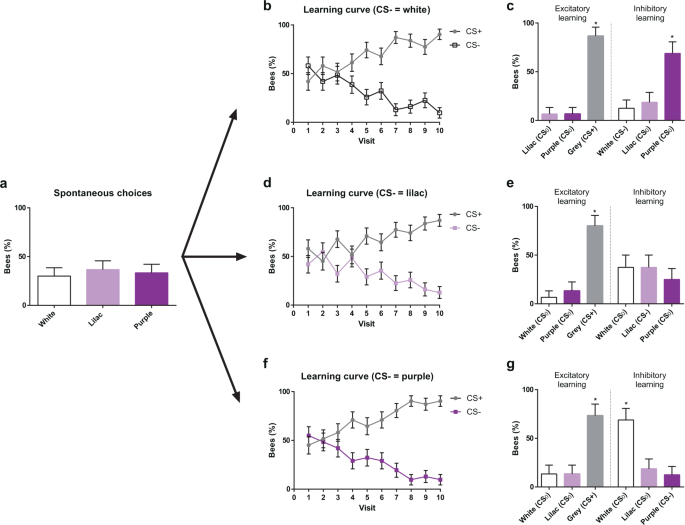

The experiment started with a spontaneous-preference test, in which each bee was presented with three non-rewarding artificial flowers, each displaying a different colour, white, purple or lilac, and a single choice was recorded per bee. The three colours were aligned along a continuum in the colour hexagon, with lilac being intermediate between white and purple (see Fig. 1c). No significant preference was found for any of these three colours (Fig. 3a; white = 30.00%, lilac = 36.66%, purple = 33.33%, χ2 = 0.2993, df = 2, P = 0.861; n = 93).

Colour choices in a non-rewarding, continuous polymorphic scenario. (a) Spontaneous choices of a white, a lilac and a purple flower presented simultaneously. (b) Acquisition curves of bees trained along ten consecutive visits with three rewarded grey flowers (CS+) vs. three non-rewarded white flowers (CS−). (c) Tests opposing grey (CS+) to lilac and purple (both CS0) (left), and white (CS−) to lilac and purple (both CS0) (right). Bees preferred the CS+ over the two CS0. When presented with the CS−, they preferred the CS0 (purple) that had the largest difference to the CS− white. In this case, the intermediate CS0 (lilac) was treated as the CS−. (d) Acquisition curves of bees trained along ten consecutive visits with three rewarded grey flowers (CS+) vs. three non-rewarded lilac flowers (CS−). (e) Tests opposing grey (CS+) to white and purple (both CS0) (left), and lilac (CS−) to white and purple (both CS0) (right). Bees preferred the CS+ over the two CS0. They distributed equally their choices between the CS− lilac and the two adjacent CS0 colours, thus showing inhibitory generalization from the CS− to the CS0 colours. (f) Acquisition curves of bees trained along ten consecutive visits with three rewarded grey flowers (CS+) vs. three non-rewarded purple flowers (CS−). (g) Tests opposing grey (CS+) to white and lilac (both CS0) (left), and purple (CS−) to white and lilac (both CS0) (right). Bees preferred the CS+ over the two CS0. When presented with the CS−, they preferred the CS0 (white) that had the largest difference to the CS− purple. The intermediate CS0 (lilac) was treated as the CS−. *P < 0.05. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.).

After the spontaneous-preference test, three groups of bees were trained to forage on six artificial flowers, three of which displayed the grey colour (CS+) and were rewarded with 50% (w/w) sucrose solution, while the other three displayed either the white, the lilac or the purple colour (CS−) and were non-rewarded (n = 31 for each group).

Figure 3b,d,f shows the learning curves of the three groups of bees trained to choose the grey CS+ colour vs. their respective CS− colour, white, lilac or purple. As in the previous experiment, the % of bees choosing the grey rewarding flowers increased during the ten flower choices; accordingly, the choice of the CS− colour decreased proportionally (CS− white, χ2 = 30.088, df = 9, P < 0.01, n = 31; CS− lilac, χ2 = 21.801, df = 9, P < 0.01, n = 31; CS− purple, χ2 = 30.903, df = 9, P < 0.01, n = 31). No significant differences were found in discrimination success between the three groups of bees (χ2 = 11.6943, df = 18, P = 0.862), thus showing that differences in chromatic contrast between the CS+ and the CS− did not influence discrimination learning.

After finalizing the tenth flower visit, each group of bees was split in two subgroups to perform a single test per subgroup. In these tests, three non-rewarded flowers were presented and a single choice was recorded per bee. In one test, one of the flowers presented the grey CS+ colour and the other two flowers the novel CS0 colours (i.e. purple and lilac for bees trained with white as CS−, purple and white for bees trained with lilac as CS−, and white and lilac for bees trained with purple as CS−). In the other test, bees were confronted with their CS− colour vs. the two novel CS0 colours.

In the test confronting the grey colour to the two novel colours (Fig. 3c,e,g, ‘Excitatory learning’), bees preferred significantly the previously rewarded grey colour (CS− white: grey = 86.66%, lilac = 6.66%, purple = 6,66%; χ2 = 18.288, df = 2, P < 0.01, n = 15; CS− lilac: grey = 80.00%, white = 6.66%, purple = 13.33%; χ2 = 16.067, df = 2, P < 0.01, n = 15; CS− purple: grey = 73.33%, white = 13.33%, lilac = 13.33%; χ2 = 13.210, df = 2, P < 0.01, n = 15; see Supplementary Table S1). This result confirms that bees were guided by the appetitive outcome obtained on the grey colour during training.

In the test confronting the CS− colour to the CS0 colour (Fig. 3c,e,g, ‘Inhibitory learning’), bees exhibited significant preferences if their CS− was either white or purple, i.e. one of the extremes of the continuum (CS− white: white = 12.50%, lilac = 18.75%, purple = 68,75%; χ2 = 11.614, df = 2, P < 0.01, n = 16; CS− purple: white = 68.75%, lilac = 18.75%, purple = 12,50%; χ2 = 11.614, df = 2, P < 0.001, n = 16; Fig. 3c,g; see Supplementary Table S1). In these cases, the bees preferred the colour that was more distinct from the CS− (white for bees trained with purple as the CS− and purple for bees trained with white as the CS−; hexagon distances > 0.1 units). The intermediate colour lilac was treated as being similar to the CS− as responses to it did not differ significantly from those to the CS− (see Supplementary Table S1 for details). When the CS− was the intermediate colour lilac, the bees visited equally all three colours (CS− lilac: white = 37.50%, lilac = 37.50%, purple = 25,00%; χ2 = 0.740, df = 2, P = 0.690, n = 16; Fig. 3e), which indicates high generalization between these stimuli. These results reveal that during the training, the bees learned the inhibitory properties of the CS−, which led them to avoid this colour in favour of the more discriminable novel stimulus available during the test. Intermediate stimuli were assimilated to the CS− and treated similarly. When the CS− was the intermediate colour, inhibition was generalized to the two adjacent colours and the proportion of choices for the three alternatives was low.

The results of this experiment thus indicate again that a bee driven by appetitive expectations and having experienced a negative outcome in a non-rewarding coloured orchid morph, will avoid further flowers displaying the same colour, and will generalize this inhibition towards similar colours. On the contrary, it will orient its choice towards a morph distinctly coloured, favouring thereby colours at the extremes of the colour continuum.

Comparing monomorphic and polymorphic colour scenarios: the number of visits and time spent exploring non-rewarding flowers

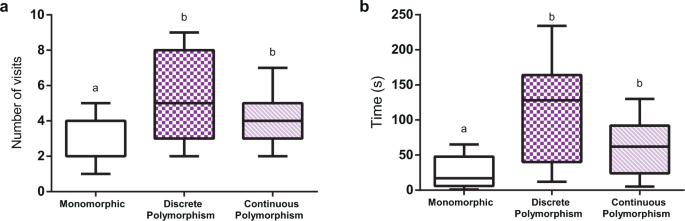

Colour variability may be an essential component to promote and maintain further visiting of a non-rewarded, variable floral species10. The degree of colour variability may directly translate into the time required by a pollinator to learn to avoid this species. To investigate this hypothesis, we compared the performance of bees foraging in a patch of artificial flowers displaying three distinct scenarios: i) a monomorphic situation, in which eight flowers presented the same colour (either white, purple or lilac), ii) a discrete polymorphic scenario with eight flowers, four of which were white and the other four purple, and iii) a continuous polymorphic scenario, in which nine flowers were presented to balance the spatial distribution of three colours (three purple flowers, three white flowers and three lilac flowers). Bees were previously pre-trained to visit the patch presenting eight rewarding artificial flowers during ten consecutive choices. During these pre-training visits, no colours were presented in the flowers, i.e. only the transparent Plexiglas flowers lay flat on the green background of the setup. After the tenth choice, and when the marked bee returned to the hive, the setup was cleaned and experimental conditions were changed to test its performance in one of the three scenarios described. For each scenario, we quantified the number of visited flowers and the total time spent (in seconds) at the experimental setup before abandoning it for more than one min. Bees usually required one min or less to return to the area from their nest.

Figure 4 shows the number of flowers visited and the time spent at the patch before abandoning it. For the monomorphic scenario, which could be either white (n = 15), purple (n = 15) or lilac (n = 15), no significant effect of stimulus identity was found (number of visits: χ2 = 0.1168, df = 2, P = 0.73; total time: χ2 = 0.0199, df = 2, P = 0.88), which allowed us to pool the data for this condition. In a monomorphic patch, bees visited relatively few flowers (2.56 ± 1.30; mean ± S.E.) before deciding to quit (Fig. 4a) and spent in average 26.13 ± 22.18 s while doing so (Fig. 4b). In both polymorphic scenarios (n = 15 each), on the contrary, bees visited more flowers (discrete polymorphism: 5.2 ± 2.3; continuous polymorphism: 4.26 ± 1.57) and spent more time at the patch before abandoning it (discrete polymorphism: 110.06 ± 72.08 s; continuous polymorphism: 62.80 ± 39.09 s). Comparing the three conditions thus revealed significant differences both for the number of flowers visited (Fig. 4a; χ2 = 20.376, df = 2, P < 0.001) and for the time spent at the patch (Fig. 4b; χ2 = 28.191, df = 2, P < 0.001). Differences were introduced by the monomorphic scenario as comparing the discrete and continuous polymorphic scenarios yielded no significant differences both for the number of visits and time spent at the patch (see Supplementary Table S2 for details).

Number of visits and time before quitting a non-rewarding patch. Three scenarios are compared, all presenting non-rewarding flowers: i) a monomorphic patch with eight flowers presenting the same colour (either white, purple or lilac), ii) a discrete polymorphic patch with eight flowers, four of which were white and the other four purple, and iii) a continuous polymorphic patch, with nine flowers, three purple, three white and three lilac. (a) number of visited flowers and (b) time spent at the patch before quitting. Different letters above columns indicate significant differences. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.).

Thus, after a rewarding experience at the patch (the pre-training period), the presence of colour variability in the artificial flowers promoted more visiting to non-rewarding flowers and increased the searching time at the patch. No differences between a continuous and a discrete polymorphic situation were found in our experimental situation.

Source: Ecology - nature.com