Experimental site

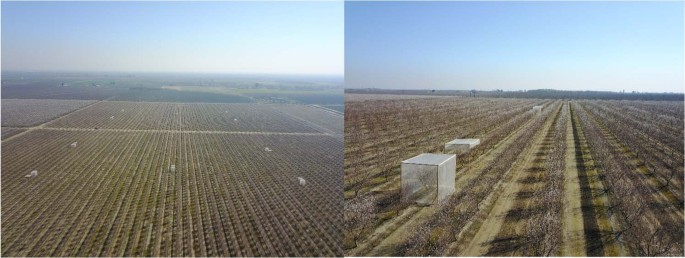

The experiment was carried out from February to August 2018. The site was located in Kings County (36° 21.698′ N, 119° 42.263′ W) California, USA. We selected young almond trees for this experiment, because kernel quantity and quality of whole trees can be measured, and accumulated resources are limited in smaller trees29,30, which make any test on pollinator dependence more conservative. Two 20-ha plots planted with 50–50% of Nonpareil – Independence tree varieties were used to perform the experiment. Sampled trees were approximately 4-m tall and had been harvested twice before this study. Honey bee colonies were placed at a stocking rate of five colonies/ha surrounding the experimental study site and were part of the commercial pollination management system used by the grower.

Experimental design

To evaluate honey bee effects on fruit set, and kernel yield quantity and quality at tree level, we randomly selected 30 experimental almond trees of Independence variety on two plots (i.e., 15 trees per plot). To each tree, we assigned one of the following treatments: (i) isolation (i.e., trees were isolated from bees by covering them with a fine mesh 10% Crystal, Green-tek, Sultana, California 93666), (ii) open (i.e., trees were kept open to bees), and (iii) control (i.e., trees covered with mesh above and along a fringe on the sides, without interfering with bee visitation, to control for effects of the net on attenuating irradiation and frost) (see Fig. 1 in main text and Supplementary Information S1). Each treatment (isolation, open, control) was replicated in 10 trees. Treatments were set in “blocks”, consisting of a group of three neighboring trees, each one randomly assigned one the three different pollination treatments (see Fig. 1 and Supplementary Information S1). In the isolation and control treatments, trees were mesh-covered before blooming started and the mesh immediately removed after bloom was over.

Data collection and analysis

Bee visitation

In open-pollinated and mesh-control trees, we performed 43 pollinator censuses, respectively. The censuses consisted in recording the number of flowers visited by each visiting pollinator to a group of flowers for a period of 5 min (i.e., no. visits · flower−1 · 5 min−1), totaling ~7 h of observation. Whenever possible, censuses of open and control trees were made simultaneously. The number of observed flowers per census was, on average (±SE), 52 ± 2.54. Each census conducted on each tree, involved a different randomly selected group of flowers. Each tree was surveyed between 11:00 and 17:00. During pollinator censuses, we recorded only flower visitors that contacted anthers and/or stigma. Furthermore, the enclosure of the isolated trees was checked throughout the flowering period to certify the absence of bees.

We evaluated the effect of pollination treatment (open and control) on visitation frequency to flowers with a generalized linear mixed-effects model. Data analysis was carried out using the lmer function from the lme4 package31 of the R software32. Because response variables were counts (i.e., visits), we used a Poisson error distribution with a log link function. We included number of flowers observed in each census as an offset (i.e. a fixed predictor known in advance to influence insect visitation)33. The pollination treatment was included in the model as fixed effect and each tree nested within a block as a random effect, allowing the intercept to vary among blocks/trees.

Fruit set

We tagged five branches in each experimental tree (totaling 150 experimental branches) in which we counted the number of open flowers between the tag and the end of the branch. After bloom, we counted the number of developing fruits to estimate initial fruit set (i.e. fruits/flower ratio). Considering that during “June drop” trees lose many fruits, we made a second measurement of fruits retained by trees right before harvest to estimate final fruit set.

We evaluated the effects of the pollination treatment (i.e., isolation, open, and control) on the initial and final probability of a flower setting a fruit with a generalized linear mixed-effects model. Data analysis was carried out using the lmer function from the lme4 package31 of the R software32. Because the response variable is binary (i.e., a flower setting or not a fruit), the model assumed a binomial error distribution with a logit link function. Pollination treatment was considered as a fixed effect and each tree nested within a block as a random effect.

Fruit weight and yield

At fruit maturity, all fallen fruits were collected, after shaking the trees, and sun-dried for 5 days. From each tree, we randomly sampled 70 fruits, totaling 2100 fruits (i.e., 70 fruits/ tree × 10 trees/ treatment × 3 treatments). From each individual fruit, we weighed pericarp, endocarp, and kernel (see Supplementary Information S3). Then, we weighed the entire fruit production of each experimental tree with a hand digital scale. To estimate kernel production for each tree, we multiplied total fruit weight times the average proportion of a fruit’s weight represented by the kernel (see Supplementary Information S3).

We used an ANOVA model to estimate the effect of pollination treatment (isolation, open, and control) on kernel production at tree level. Data analysis was carried out using the gls function from the R software32. Because our data did not comply with the assumption of homogeneous variance, we re-ran the analysis using a heterogeneous variance model with the varIdent function, which increased model fit (lower AIC) and provided compliance with model assumptions. We made multiple comparison of means with Tukey post-hoc test using the glht function from the multcomp package34.

Kernel nutritional quality

We randomly collected ~50 fruits from each tree to estimate kernel nutritional quality. Samples were stored in paper bags and kept at room temperature until laboratory analyses. Fats are the main nutritional component in almond28. In particular, clinical studies have shown benefits to human health of mono-unsaturated fats present in almonds35. Here we described and analyzed almond’s fatty acid portion. In particular, we estimated the oleic to linoleic acid ratio, which is the most common measure to determine almond nutritional quality27. Details of analytical methods employed for estimations of fatty acid composition are provided in the Supplementary Information S2.

We estimated effects of the pollination treatment (isolation, open, and control) on almond’s oleic and linoleic acid content, and oleic to linoleic ratio at tree level by means of an ANOVA model. Data analysis was carried out using the lm function from the R software32. We made multiple comparison of means with Tukey post-hoc tests using the glht function from the multcomp package34.

Source: Ecology - nature.com