Historical background

All of the individuals in this study were evacuated from Finnish Karelia during the Second World War. The Soviet Union invaded Finland in 1939, starting the Winter War. As part of the Moscow Peace Treaty of 1940, Finland ceded territory, including Karelia, to the Soviet Union, and evacuated the entire population to the rest of Finland. Many evacuees moved back49 during the Continuation War (1941–1944), which saw Finland briefly reclaim this lost territory. However, the Soviet Union once again conquered Finnish Karelia in 1944, and the territory permanently moved into Soviet possession with the signing of Moscow Armistice agreement. Again, the population that had returned was evacuated and settled in western Finland.

Lotta Svärd organization

Founded in 1920, the Lotta Svärd organization was a volunteer paramilitary organization for women which provided much needed military support to the Finnish armed forces. Members operated at the front lines as well as on the home-front in various duties included nursing, food service, anti-aircraft spotting, fundraising, and messenger activities. The youth corps was created in 1931 for children aged 8–16, with 14–16 year olds taking on duties with greater responsibility. In total, there were 221,613 volunteers in the adult and youth corps by the end of the war56.

Girls between the ages of 8 and 16 could, with the permission of their parents, join the “Lotta Girls”, who were trained for future roles in adult Lotta divisions and entrusted with tasks such as knitting socks and gloves, writing letters to frontline soldiers, and attending the funerals of soldiers killed in action. When these girls turned 17, they could apply to the adult service divisions. However, due to personnel shortages toward the end of the war, “Lotta Girls” aged 14–16 were given more responsibilities and were allowed to participate in some of the more demanding roles usually reserved for adult Lottas. This meant that girls as young as 16 were sent to the front lines to participate in the same activities as their adult peers. Behind the front lines girls were allowed to assist in military hospitals and with preparation of war dead. Comparing these activities to the wartime activities of women who did not volunteer is difficult because the tasks and hardships of women who did not volunteer were so varied. Although we have no data on food consumption during the war, the historic record indicates that the basic needs were met for all citizens, with the exception of short periods of starvation-level caloric intake occurring for some members of the military31. Therefore, in terms of caloric intake, the food rations of Lottas were unlikely to have been any better, and perhaps were a bit worse, than those of women on the home front. All women in our analysis were at least 17 years old by the end of the war.

Data

Structured interviews of evacuees from Finnish Karelia during World War II were published in a four volume set called “Siirtokarjalaisten tie”57. These records were compiled in an effort to record the lives of the Karelian evacuees during World War II. Over 300 individuals were trained to conduct these interviews, which took place between 1968 and 1970. During this time, an effort was made to locate everyone evacuated from Karelia during the war. Each entry in the published books lists the name, sex, date of birth, birthplace, occupation, year of marriage, reproductive records (name, sex, and date of birth of all children) and membership in various organizations, including Lotta Svärd. If they were married, the name, date of birth, birthplace, and occupation of their spouse are also listed. These books were scanned with optical character recognition software, and additional software was developed (Kaira Core and Natural Language Processing software designed for use with the Finnish language) to digitize and extract these records (see Loehr et al.58 for more details on data extraction methods and the construction of the database). Overall, there were data on 163,152 individuals, including spouses, but here we focus on a subset of 37,613 women (31,613 of whom had at least one child), all of whom were evacuees, and for whom we had complete and credible records on their year of birth, place of birth, occupation, and years of birth of all their children. Of these individuals, 4261 were listed as members of Lotta Svärd and were between the ages of 12 and 40 in 1939. Finally, we were able to link some of the women in our data by their full names and exact dates of birth to a historical genealogy which uses digitized Finnish church records called “Karjala-tietokanta”59. We used these data to find a subset of 2671 women (477 were Lottas) who had at least one full sister and who were between the ages of 12 and 40 in 1940 (N = 2272 reproduced of which 359 were Lottas). All R code for analysis, figures, and data selection is publicly available and can be found on Github60.

Statistical analysis

To analyze the reproductive timing and lifetime reproductive success of Lotta Svärd volunteers, we used the rethinking package35 in R Studio 3.3.3 to run a GLMM regression. Model fitting was performed using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo resampling, which draws samples from the posterior distribution, and was implemented with version 2.12 of Stan61. We used Bayesian inference for all statistical analyses, and assessed convergence of the four Markov chains by inspection of the trace plots (see Supplementary Materials: Figs. 6a, b and 7a, b), Gelman–Rubin R2, and an estimate of the effective number of samples. Healthy trace plots generally show good mixing (i.e., the chains crossover each other early and often), stability (they converge on a single parameter estimate (y-axis) across iterations (x-axis) and tend to remain in that area). In a Bayesian framework, each model conditions data on prior probability distributions and uses Monte-Carlo methods to generate posterior distributions for each of the parameters. The priors are the initial probabilities for the values of each parameter. This type of analysis allows us to compare posterior distributions across occupational categories, age groups and educational backgrounds without relying on specific post hoc tests36 and averts the need to adjust for multiple comparisons62. We are also better able to visualize and interpret differences between parameter estimates relative to a specific value by reporting and displaying the entire posterior distribution for each predictor and showing the highest density intervals (HDI) to reveal the most credible values for each parameter estimate. Here, we assume that a parameter value was credibly different from the baseline if the 95% HDI did not include zero.

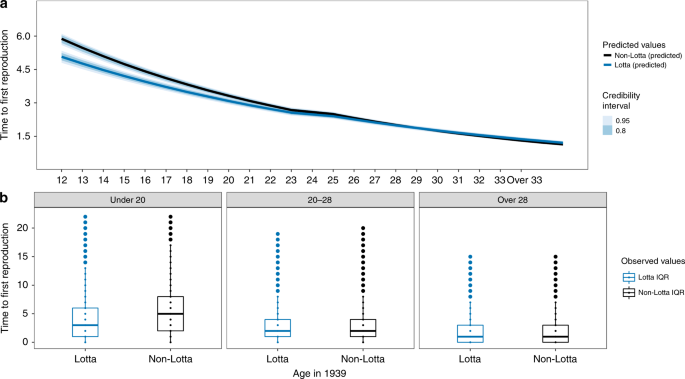

To analyze how volunteering for Lotta Svärd impacted reproductive timing and reproductive success, we generated three models. Each was designed to predict three distinct outcomes: Model 1: Time to first birth after the war (N = 31,613); Model 2: Mean birth intervals after the war (N = 31,613); and Model 3: Total reproduction after the war (N = 37,613)(see Supplementary Materials Table 1—right side). To compare the results of these models with models of female reproductive schedules before the war, we used a subset of these same individuals who had given birth to at least one child before the war (N = 9862) and used their age at first birth as their time to first birth Model 1 before the war. For the mean interbirth intervals before the war these sample criteria were even more restricted and were limited to women who had two or more children before the war began (N = 5603) in order to be able to accurately calculate a prewar IBI Model 2. However, the same sample of women were used to model overall reproduction before the war Model 3 (N = 37,613). In models 1 and 2, we initially included only women who had reproduced, as nonreproductive women cannot, by definition, have mean IBI or time to first birth. Additional models were therefore developed to determine the models sensitivity to excluding nonreproductive women from models 1 and 2 (see Supplementary Materials: Table 3). We also ran each of these models again with all of the same covariates (see Supplementary Materials: Table 2) but this time on a subset of women who we were able to link to a historical genealogy59. In these analyses we included all women whose parents were known and who had at least one sister (N = 2272 for time to reproduction and mean birth intervals after the war and N = 2671 for total reproduction). In this subset, the sisters within a family could either be one Lotta and one non-Lotta, both Lottas or both non-Lottas. For this subset we ran the three models again, but this time included parent id as a random (clustering) intercept to control for within family effects63. As described above, the criteria for individuals to be included in the models run to analyze reproductive schedules before the war for the sisters only sample were more restricted for the models used to predict time to first reproduction (N = 729) and for mean IBI (N = 268), but was the same for the model used to predict overall reproduction (N = 2671).

The predictor variables for all analyses were as follows: age when the war ended in 1945 (scaled by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation of the entire vector using the “scale” function in R 3.5.164), dummy variables encoding whether or not their occupation required an education (binary: 1 = yes, 0 = no), whether or not they were a farmer (binary: 1 = farmer, 0 = not a farmer), whether their first child was born after the war (binary: 1 = yes, 0 = no), whether or not they had given birth within the previous 2 years (binary: 1 = yes, 0 = no), whether or not they had volunteered for Lotta Svärd (binary: 1 = yes, 0 = no), and an interaction between their age in 1945 and whether or not they had volunteered. Finally, place of birth (N = 991) was entered as a random effect into all models. Agriculture and education were entered into the models because previous analyses have shown that these categories explain much of the variance in social status and social integration among this population32. “First child born after the war” was used to parse the effects of including women who had already had a child before 1945. For some analyses we replaced this variable with a dummy variable “Married before the war” (see Supplementary Materials Table 7). These two variables could not be entered into the same models because they were highly correlated (r = 0.70). However, because “wedding year” was not available for 15,472 women (approximately 41% of our full sample) we only used the dummy variable “Married before the war” in models in which we were primarily concerned with analyzing the effects of being married on reproductive outcomes. The variable “reproduced within the last 2 years” was entered to control for the reduced fertility of women following a birth65. The interaction between volunteer status (Lotta) and a woman’s age during the war was the predictor of interest.

Statistical analyses for all models were performed in R version 3.3.2 and Bayesian inference used to conduct analyses for Models 1–3 was carried out using the rstan package for R version 2.14.166 an interface to Stan which uses a Hamiltonian Monte Carlo sampler67. We used the rethinking R package version 1.5935, which includes convenience functions for building, sampling, and summarizing models with a Bayesian framework36. The replicate models using all women, including nonreproductives, used Cox proportional hazards regression models, implemented with the functions coxph and Surv from the survival package [version 2.44-1.1]68. This allowed us to account for censored data—in this case, right censored at 25 years (the number of years from 1945 to the interviews). Though this may bias estimates upwards for older women, the level of censoring was similar between Lottas and non-Lottas.

A small subset of volunteers in our data identified the specific units to which they were assigned. We created two broad categories based on these identifications that we hoped would capture the level of threat and exposure to mortality that different types of volunteers faced. Canteen workers, nurses and anti-aircraft volunteers were all either stationed nearer to the front lines or spent more time in hospitals and were therefore categorized as “More exposed to combat” while office workers and organizational volunteers spent less time close to combat and hospitals and were therefore categorized as “Less exposed to combat”69. We analyzed time to reproduction, IBI and overall reproduction after the war for these two types of volunteers (see “Results”).

Model validity, effects, and specifications

To assess the validity of these models and their ability to reverse engineer the observed data, we conducted a posterior predictive check (see Supplementary Materials: Fig. 3a, b for the models including the full sample and Fig. 4a, b for the sisters only models). Bayesian models are generative, which means that the posterior distributions produced by these models (see Supplementary Materials: Figs. 1a, b and 2a, b) can be used to make specific predictions on counterfactual data. This also allows us to determine the absolute effect—the practical change in the probability of an outcome occurring that depends on the values of all of the other covariates in the model—that specific parameters of interest have on outcomes. These predictions are generated from the model to construct posterior predictions for a previously unobserved, fictitious, and potentially impossible person. For example, this might be a Lotta Svärd volunteer who is 15 years old when the war breaks out, has a mean education identical to that of our sample, an occupation of average “agriculturalness”, and has the mean of the sample values for the dummy variables “reproduced within the last 2 years” and “first child born after the war”. These factors are then used by the model to generate predicted posterior distributions. Hamiltonian Monte Carlo Chains, programmed in STAN via the rstan interface, were used to generate these posterior distributions. Broad but weakly regularizing priors that tamp the effects of extreme values were specified for these models as follows: normal distributions of discrete variables were centered on 0, normal distributions of continuously varying covariates were centered on null-hypothesized isometric slopes, and standard deviations were specified as Cauchy distributions with a shape parameter of 1. Models were run with four replicate chains for 6000 MCMC iterations, of which 2000 were warm-up iterations. See Supplementary Fig. 6a, b for trace plots generated by these chains.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Source: Ecology - nature.com