Clements, D. R., Feenstra, K. R., Jones, K. & Staniforth, R. The biology of invasive alien plants in Canada. 9. Impatiens glandulifera Royle. Can. J. Plant Sci. 88, 403–417. https://doi.org/10.4141/CJPS06040 (2008).

2Cockel, C. P. & Tanner, R. A. Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Himalayan balsam) in A Handbook of Global Freshwater Invasive Species (ed Francis, R. A.) 67–77 (Earthscan, London, 2011).

Prentis, P. J. et al. Understanding invasion history: genetic structure and diversity of two globally invasive plants and implications for their management. Divers. Distrib. 15, 822–830. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2009.00592.x (2009).

Beerling, D. J. & Perrins, J. M. Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Impatiens roylei Walp). J. Ecol. 81, 367–382. https://doi.org/10.2307/2261507 (1993).

Tanner, R. A. An Ecological Assessment of Impatiens glandulifera in its Introduced and Native Range and the Potential for its Classical Biological Control. Ph.D thesis thesis, Royal Holloway, University of London, London (2011).

Morgan, R. J. Impatiens: The Vibrant World of Busy Lizzies, Balsams, and Touch-Me-Nots (Timber Press, Oregon, 2007).

Hulme, P. E. & Bremner, E. T. Assessing the impact of Impatiens glandulifera on riparian habitats: partitioning diversity components following species removal. J. Appl. Ecol. 43, 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2005.01102.x (2006).

Tanner, R. A. et al. Impacts of an invasive non-native annual weed, Impatiens glandulifera, on above-and below-ground invertebrate communities in the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE 8, e67271. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067271 (2013).

Pattison, Z. et al. Positive plant–soil feedbacks of the invasive Impatiens glandulifera and their effects on above-ground microbial communities. Weed Res. 56, 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/wre.12200 (2016).

Chittka, L. & Schürkens, S. Successful invasion of a floral market. Nature 411, 653. https://doi.org/10.1038/35079676 (2001).

Greenwood, P. & Kuhn, N. J. Does the invasive plant, Impatiens glandulifera, promote soil erosion along the riparian zone? An investigation on a small watercourse in northwest Switzerland. J. Soils Sed. 14, 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-013-0825-9 (2014).

Tanner, R. A. et al. Puccinia komarovii var. glanduliferae var. nov.: a fungal agent for the biological control of Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera). Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 141, 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-014-0539-x (2015).

Varia, S., Pollard, K. & Ellison, C. Implementing a novel weed management approach for Himalayan balsam: progress on biological control in the UK. Outlooks Pest Manage. 27, 198–203. https://doi.org/10.1564/v27_oct_02 (2016).

Ellison, C. A., Pollard, K. M. & Varia, S. Potential of a coevolved rust fungus for the management of Himalayan balsam in the British Isles: first field releases. Weed Res. 60, 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/wre.12403 (2020).

Ellison, C. A., Evans, H. C. & Ineson, J. The significance of intraspecies pathogenicity in the selection of a rust pathotype for the classical biological control of Mikania micrantha (mile-a-minute weed) in Southeast Asia. In Proceedings of the XI International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds (eds Cullen, J. M. et al.) 102–107 (CSIRO Entomology, Canberra, 2004).

Smith, L. et al. The importance of cryptic species and subspecific populations in classic biological control of weeds: a North American perspective. Biocontrol 63, 417–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-017-9859-z (2018).

Thrall, P. H. & Burdon, J. J. Host–pathogen life history interactions affect biological control success. Weed Technol. 18, 1269–1274. https://doi.org/10.1614/0890-037X(2004)018[1269:HLHIAB]2.0.CO;2 (2004).

Gaskin, J. F. et al. Applying molecular-based approaches to classical biological control of weeds. Biol. Control 58, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2011.03.015 (2011).

St. Quinton, J. M., Fay, M., Ingrouille, M. & Faull, J. Characterisation of Rubus niveus: a prerequisite to its biological control in oceanic islands. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 21, 733–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583157.2011.570429 (2011).

Goolsby, J. A., Van Klinken, R. D. & Palmer, W. A. Maximising the contribution of native-range studies towards the identification and prioritisation of weed biocontrol agents. Aust. J. Entomol. 45, 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-6055.2006.00551.x (2006).

Nissen, S. J., Masters, R. A., Lee, D. J. & Rowe, M. L. DNA-based marker systems to determine genetic diversity of weedy species and their application to biocontrol. Weed Sci. 43, 504–513. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043174500081546 (1995).

Gaskin, J. F., Zhang, D. Y. & Bon, M. C. Invasion of Lepidium draba (Brassicaceae) in the western United States: distributions and origins of chloroplast DNA haplotypes. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2331–2341. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02589.x (2005).

Morin, L. & Hartley, D. Routine use of molecular tools in Australian weed biological control programmes involving pathogens. In Proceeding of the XIIth International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds (eds Julien, M. H. et al.) (CAB International, Wallingford, 2008).

Paterson, I. D., Downie, D. A. & Hill, M. P. Using molecular methods to determine the origin of weed populations of Pereskia aculeata in South Africa and its relevance to biological control. Biol. Control 48, 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2008.09.012 (2009).

Sutton, G., Paterson, I. & Paynter, Q. Genetic matching of invasive populations of the African tulip tree, Spathodea campanulata Beauv. (Bignoniaceae), to their native distribution: Maximising the likelihood of selecting host-compatible biological control agents. Biol. Control 114, 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2017.08.015 (2017).

Saltonstall, K. Cryptic invasion by a non-native genotype of the common reed, Phragmites australis, into North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 2445–2449 (2002).

Trewick, S. A., Morgan-Richards, M. & Chapman, H. M. Chloroplast DNA diversity of Hieracium pilosella (Asteraceae) introduced to New Zealand: reticulation, hybridization, and invasion. Am. J. Bot. 91, 73–85 (2004).

Love, H. M., Maggs, C. A., Murray, T. E. & Provan, J. Genetic evidence for predominantly hydrochoric gene flow in the invasive riparian plant Impatiens glandulifera (Himalayan balsam). Ann. Bot. 112, 1743–1750. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mct227 (2013).

Hagenblad, J. et al. Low genetic diversity despite multiple introductions of the invasive plant species Impatiens glandulifera in Europe. BMC Genet. 16, 103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-015-0242-8 (2015).

Nagy, A.-M. & Korpelainen, H. Population genetics of Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera): comparison of native and introduced populations. Plant Ecol. Divers. 8, 317–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/17550874.2013.863407 (2015).

31Barrett, S. Genetic variation in weeds. In Biological control of weeds with plant pathogens (eds Charudattan, R. & Walker, H.) 73–98 (1982).

Burdon, J. & Marshall, D. Biological control and the reproductive mode of weeds. J. Appl. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.2307/2402423 (1981).

Charudattan, R. Ecological, practical, and political inputs into selection of weed targets: what makes a good biological control target?. Biol. Control 35, 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2005.07.009 (2005).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis (Springer, New York, 2016).

Dunnington, D. ggspatial: spatial data framework for ggplot2. https://cran.r-project.org/package=ggspatial (2018).

Pebesma, E. Simple features for R: standardized support for spatial vector data. R J. 10, 439–446. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2018-009 (2018).

South, A. R natural earth: world map data from natural earth. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rnaturalearth (2017).

South, A. rnaturalearthdata: world vector map data from Natural Earth used in ‘rnaturalearth’. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rnaturalearthdata (2017).

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. https://www.R-project.org/ (2018).

QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. https://qgis.osgeo.org/ (2020).

Hasan, S. Search in Greece and Turkey for Puccinia chondrillina strains suitable to Australian forms of skeleton weed. In Proceeding of the VI International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds (ed. Delfosse, E. S.) 625–632 (Canada Agriculture, Ottawa, 1985).

Kress, W. J. et al. Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 8369–8374. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0503123102 (2005).

Birky, C. W. Uniparental inheritance of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes: mechanisms and evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 11331–11338. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.92.25.11331 (1995).

Provan, J., Powell, W. & Hollingsworth, P. M. Chloroplast microsatellites: new tools for studies in plant ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 142–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(00)02097-8 (2001).

Fry, C. The Plant Hunters (Andre Deutsch, London, 2017).

Jukonienė, I., Subkaitė, M. & Ričkienė, A. Herbarium data on bryophytes from the eastern part of Lithuania (1934–1940) in the context of science history and landscape changes. Botanica 25, 41–53. https://doi.org/10.2478/botlit-2019-0005 (2019).

Janssens, S. B. et al. Rapid radiation of Impatiens (Balsaminaceae) during Pliocene and Pleistocene: result of a global climate change. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 52, 806–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2009.04.013 (2009).

Barreto, R. W., Ellison, C. A., Seier, M. K. & Evans, H. C. Biological control of weeds with plant pathogens: four decades on. In Integrated Pest Management: Principles and Practice (eds Abrol, D. P. & Shankar, U.) 299–350 (CAB International, Wallingford, 2012).

Kniskern, J. & Rausher, M. D. Two modes of host–enemy coevolution. Popul. Ecol. 43, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00012012 (2001).

Evans, H. C., Greaves, M. P. & Watson, A. K. Fungal biocontrol agents of weeds. In Fungi as Biocontrol Agents: Progress, Problems and Potential (eds Butt, T. M. et al.) 169–192 (CABI Publishing, Wallingford, 2001).

Cullen, J. M., Kable, P. F. & Catt, M. Epidemic spread of a rust imported for biological control. Nature 244, 463–464 (1973).

Hasan, S. A new strain of the rust fungus Puccinia chondrillina for biological control of skeleton weed in Australia. Ann. Appl. Biol. 99, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7348.1981.tb05137.x (1981).

Charudattan, R. & Dinoor, A. Biological control of weeds using plant pathogens: accomplishments and limitations. Crop Protect. 19, 691–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-2194(00)00092-2 (2000).

Fröhlich, J. et al. Biological control of mist flower (Ageratina riparia, Asteraceae): transferring a successful program from Hawai’i to New Zealand. In Proceeding of the X International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds (ed. Spencer, N.) 51–57 (Montana State University, Montana, 2000).

Ellison, C. A. & Cock, M. J. W. Classical biological control of Mikania micrantha: the sustainable solution. In Invasive Alien Plants: Impacts on Development and Options for Management (eds Ellison, C. A. et al.) 162–190 (CABI, Wallingford, 2017).

Roderick, G. K. & Navajas, M. Genes in new environments: genetics and evolution in biological control. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4, 889–899. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1201 (2003).

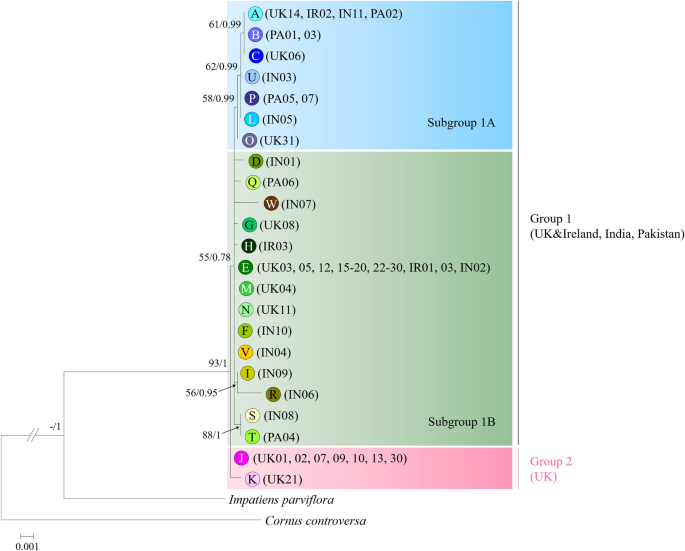

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054 (2016).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 (2014).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/sys029 (2012).

Tanabe, A. S. Kakusan4 and Aminosan: two programs for comparing nonpartitioned, proportional and separate models for combined molecular phylogenetic analyses of multilocus sequence data. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 11, 914–921. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03021.x (2011).

Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Automat. Control 19, 716–723. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705 (1974).

Rambaut, A., Suchard, M., Xie, D. & Drummond, A. Tracer v1.6. https://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/ (2016).

Rambaut, A. FigTree ver. 1.4.3. https://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree (2016).

Clement, M., Posada, D. & Crandall, K. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol. Ecol. 9, 1657–1660. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01020.x (2000).

Source: Ecology - nature.com