Hughes, J. B., Daily, G. C. & Ehrlich, P. R. Population diversity: Its extent and extinction. Science 278, 689–692 (1997).

Sala, O. E. et al. Global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100. Science 287, 1770–1774 (2000).

Barnosky, A. D. et al. Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature 471, 51–57 (2011).

Ceballos, G., Ehrlich, P. R. & Dirzo, R. Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signalled by vertebrate population losses and declines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, E6089–E6096 (2017).

Régnier, C. et al. Mass extinction in poorly known taxa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 7761–7766 (2015).

Klein, A.-M. et al. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. Biol. Sci. 274, 303–13 (2007).

Garibaldi, La et al. Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science 339, 1608–11 (2013).

Dirzo, R. et al. Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 345, 401–406 (2014).

Powney, G. D. et al. Widespread losses of pollinating insects in Britain. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–6 (2019).

Seibold, S. et al. Arthropod decline in grasslands and forests is associated with drivers at landscape level. Nature 574, 1–34. (2019).

Franco, A. M. A. et al. Impacts of climate warming and habitat loss on extinctions at species’ low-latitude range boundaries. Glob. Chang. Biol. 12, 1545–1553 (2006).

Pounds, J. A. et al. Widespread amphibian extinctions from epidemic disease driven by global warming. Nature 439, 161–167 (2006).

Gossner, M. M. et al. Land-use intensification causes multitrophic homogenization of grassland communities. Nature 540(7632), 266 (2016).

Potts, S. G. et al. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 345–53 (2010).

Didham, R. K., Tylianakis, J. M., Gemmell, N. J., Rand, T. A. & Ewers, R. M. Interactive effects of habitat modification and species invasion on native species decline. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 489–496 (2007).

Cameron, S. A. et al. Patterns of widespread decline in North American bumble bees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 662–667 (2011).

Baude, M. et al. Historical nectar assessment reveals the fall and rise of floral resources in Britain. Nature 530, 85–88 (2016).

Miyo, T., Akai, S. & Oguma, Y. Seasonal fluctuation in susceptibility to insecticides within natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Empirical observations of fitness costs of insecticide resistance. Genes Genet. Syst. 75, 97–104 (2000).

Baron, G. L., Raine, N. E. & Brown, M. J. F. General and species-specific impacts of a neonicotinoid insecticide on the ovary development and feeding of wild bumblebee queens. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 284, 20170123 (2017).

Ranjeva, S. et al. Age-specific differences in the dynamics of protective immunity to influenza. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–11 (2019).

Fransen, J. J., Winkelman, K. & van Lenteren, J. C. The differential mortality at various life stages of the greenhouse whitefly, Trialeurodes vaporariorum (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae), by infection with the fungus Aschersonia aleyrodis (Deuteromycotina: Coelomycetes). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 50, 158–165 (1987).

Sheridan, L. A. D., Poulin, R., Ward, D. F. & Zuk, M. Sex differences in parasitic infections among arthropod hosts: Is there a male bias? Oikos 88, 327–334 (2000).

Úbeda, F. & Jansen, V. A. A. The evolution of sex-specific virulence in infectious diseases. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–9 (2016).

Semlitsch, R. D., Bridges, C. M. & Welch, A. M. Genetic variation and a fitness tradeoff in the tolerance of gray treefrog (Hyla versicolor) tadpoles to the insecticide carbaryl. Oecologia 125, 179–185 (2000).

Evans, J. D., Shearman, D. C. A. & Oldroyd, B. P. Molecular basis of sex determination in haplodiploids. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 1–3 (2004).

O’Donnell, S. & Beshers, S. N. The role of male disease susceptibility in the evolution of haplodiploid insect societies. Proc. Biol. Sci. 271, 979–83 (2004).

Wilson, E.O. The Insect Societies. Harvard University Belknap Press, Cambridge, MA (1971).

Schmid-Hempel, P. Parasites in social insects. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey (1998).

Rosengaus, R. B. & Traniello, J. F. A. Disease susceptibility and the adaptive nature of colony demography in the dampwood termite Zootermopsis angusticollis. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 50, 546–556 (2001).

Calderone, N. W. Insect pollinated crops, insect pollinators and US agriculture: trend analysis of aggregate data for the period 1992–2009. PLoS One 7, e37235 (2012).

EFSA. EFSA Guidance Document on the risk assessment of plant protection products on bees (Apis mellifera, Bombus spp. and solitary bees). EFSA J. 11, 268 (2014).

Beye, M., Hasselmann, M., Fondrik, M. K., Page, R. E. Jr. & Omholt, S. W. The gene csd is the primary signal for sexual development in the honeybee and encodes an SR-type protein. Cell 114, 419–429 (2003).

Antúnez, K. et al. Immune suppression in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) following infection by Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia). Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2284–90 (2009).

Alaux, C., Ducloz, F., Crauser, D. & Le Conte, Y. Diet effects on honeybee immunocompetence. Biol. Lett. 6, 1–4 (2010).

Hornitzky, M. Nosema Disease – Literature review and three year survey of beekeepers – Part 2. RIRDC Publ., 35 (2008).

Brodschneider, R. & Crailsheim, K. Nutrition and health in honey bees. Apidologie 41, 278–294 (2010).

Tritschler, M. et al. Protein nutrition governs within-host race of honey bee pathogens. Sci. Rep., 1–11 (2017).

Adam, R., Adriana, M. & Ewa, P. An influence of chosen feed additives on the life-span of laboratory held drones and the possibility of semen collection. J. Apic. Sci. 54, 25–36 (2010).

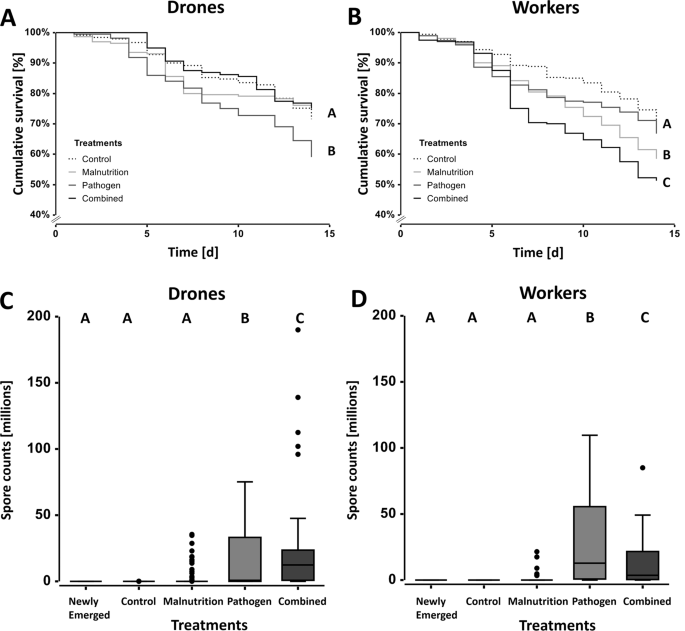

Retschnig, G. et al. Sex-specific differences in pathogen susceptibility in honey bees (Apis mellifera). PLoS One 9, e85261 (2014b).

Jack, C. J., Uppala, S. S., Lucas, H. M. & Sagili, R. R. Effects of pollen dilution on infection of Nosema ceranae in honey bees. J. Insect Physiol. 87, 12–19 (2016).

Aufauvre, J. et al. Parasite-insecticide interactions: a case study of Nosema ceranae and fipronil synergy on honeybee. Sci. Rep. 2, 326 (2012).

Mayack, C. & Naug, D. Energetic stress in the honeybee Apis mellifera from Nosema ceranae infection. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 100, 185–8 (2009).

Naug, D. & Gibbs, A. Behavioral changes mediated by hunger in honeybees infected with Nosema ceranae. Apidologie 40, 595–599 (2009).

Basualdo, M., Barragán, S. & Antúnez, K. Bee bread increases honeybee haemolymph protein and promote better survival despite of causing higher Nosema ceranae abundance in honeybees. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 6, 396–400 (2014).

Crailsheim, K. et al. Pollen consumption and utilization in worker honeybees (Apis mellifera carnica): Dependence on individual age and function. J. Insect Physiol. 38, 409–419 (1992).

Heinrich, B. Thermoregulation in endothermic insects. Science. 185(4153), 747–756 (1974).

Zheng, H.-Q. et al. Spore loads may not be used alone as a direct indicator of the severity of Nosema ceranae infection in honey bees Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera:Apidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 107, 2037–2044 (2014).

Hrassnigg, N. & Crailsheim, K. Differences in drone and worker physiology in honeybees (Apis mellifera) 1. Apidologie 36, 255–277 (2005).

Szolderits, M. J. & Crailsheim, K. A comparison of pollen consumption and digestion in honeybee (Apis mellifera carnica) drones and workers. J. Insect Physiol. 39, 877–881 (1993).

Eyer, M., Dainat, B., Neumann, P. & Dietemann, V. Social regulation of ageing by young workers in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Exp. Gerontol. 87, 84–91 (2017).

Ruiz-González, M. X. & Brown, M. J. F. Males vs workers: Testing the assumptions of the haploid susceptibility hypothesis in bumblebees. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 60, 501–509 (2006).

Cappa, F., Beani, L., Cervo, R., Grozinger, C. & Manfredini, F. Testing male immunocompetence in two hymenopterans with different levels of social organization: “live hard, die young? Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 114, 274–278 (2015).

Miller, C. V. & Cotter, S. C. Pathogen and immune dynamics during maturation are explained by Bateman’s Principle. Ecological entomology 42, 28–38 (2017).

Free, J. B. The food of adult drone honeybees (Apis mellifera). Br. J. Anim. Behav. 5, 7–11 (1957).

Kraus, F. B., Neumann, P., Scharpenberg, H., Van Praagh, J. & Moritz, R. F. A. Male fitness of honeybee colonies (Apis mellifera L.). J. Evol. Biol. 16, 914–920 (2003).

Straub, L., Williams, G. R. G. R., Pettis, J., Fries, I. & Neumann, P. Superorganism resilience: Eusociality and susceptibility of ecosystem service providing insects to stressors. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 12, 109–112 (2015).

Seeley, T. D. Life history strategy of the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Oecologia 32(1), 109–118 (1978).

Wilson-Rich, N., Dres, S. T. & Starks, P. T. The ontogeny of immunity: development of innate immune strength in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). Journal of insect physiology 54(10-11), 1392–1399 (2008).

Doums, C., Moret, Y., Benelli, E. & Schmid‐Hempel, P. Senescence of immune defence in Bombus workers. Ecological Entomology 27(2), 138–144 (2002).

Steinmann, N., Corona, M., Neumann, P. & Dainat, B. Overwintering is associated with reduced expression of immune genes and higher susceptibility to virus infection in honey bees. PloS one 10(6), e0129956 (2015).

Friedli, A., Williams, G. R., Bruckner, S., Neumann, P. & Straub, L. The weakest link: Haploid honey bees are more susceptible to neonicotinoid insecticides. Chemosphere 242, 125145 (2019).

Rosenkranz, P., Aumeier, P. & Ziegelmann, B. Biology and control of Varroa destructor. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 103, 96–119 (2010).

Williams, G. R. et al. Standard methods for maintaining adult Apis mellifera in cages under in vitro laboratory conditions. J. Apic. Res. 52, 1–36 (2013).

Currie, R. W. The biology and behaviour of drones. Bee World 68, 129–143 (1987).

Williams, G. R. et al. Deformed wing virus in western honey bees (Apis mellifera) from Atlantic Canada and the first description of an overtly-infected emerging queen. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 101, 77–9 (2009).

Dainat, B. & Neumann, P. Clinical signs of deformed wing virus infection are predictive markers for honey bee colony losses. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 112, 278–80 (2013).

Dietemann, V. et al. Standard methods for Varroa research. J. Apic. Res. 52, 1–54 (2013).

Straub, L. et al. Neonicotinoid insecticides can serve as inadvertent insect contraceptives. R. Soc. Proc. B 283, 20160506 (2016).

Chen, Y., Evans, J. D., Smith, I. B. & Pettis, J. S. Nosema ceranae is a long-present and wide-spread microsporidian infection of the European honey bee (Apis mellifera) in the United States. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 97, 186–188 (2008).

Fries, I. et al. Standard methods for Nosema research. J. Apic. Res. 52, 1–28 (2013).

Cantwell, G. E. Standard methods for counting Nosema spores. Am. Bee J. 110, 222–223 (1970).

Retschnig, G., Neumann, P. & Williams, G. R. Thiacloprid-Nosema ceranae interactions in honey bees: host survivorship but not parasite reproduction is dependent on pesticide dose. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 118, 18–9 (2014a).

Tosi, S. & Nieh, J. C. A common neonicotinoid pesticide, thiamethoxam, alters honey bee activity, motor functions, and movement to light. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–13 (2017).

Paxton, R. J., Klee, J., Korpela, S. & Fries, I. Nosema ceranae has infected Apis mellifera in Europe since at least 1998 and may be more virulent than Nosema apis. Apidologie 38, 558–565 (2007).

NCSS 2019 Statistical Software. NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah, USA, ncss.com/software/ncss (2019).

Pirk, C. W. W. et al. Statistical guidelines for Apis mellifera research. J. Apic. Res. 52, 1–24 (2013).

Folt, C. L., Chen, C. Y., Moore, M. V. & Burnaford, J. Synergism and antagonism among multiple stressors. Limmol. Ocean. 44, 864–877 (1999).

Straub, L. et al. Neonicotinoids and ectoparasitic mites synergistically impact honeybees. Sci. Rep. 9, 8159 (2019).

Hay, M. E. Defensive synergisms? Reply to Pennings. Ecology 77, 1950–1952 (1996).

Source: Ecology - nature.com