Cardinal temperature data collection

Minimum (Tmin), optimum (Topt) and maximum (Tmax) temperatures (collectively ‘cardinal temperatures’) of five life-cycle processes (DD, FR, IN, SG and SP), as well as GC (collectively ‘biological processes’), were extracted and thence digitized from ref. 15 for fungi and oomycete species. Biological processes such as wood decay, spore discharge, enzyme production, and saltation were excluded due to paucity of data. This dataset is hereafter referred to as the ‘Togashi dataset’ (see Data availability). In brief, ref. 15 is a compilation of published literature regarding plant pathogen temperature relations, published (in print) in 1949. Ref. 15 contains over 300 pages of data from over 1000 publications (published in the 19th and 20th century). To our knowledge ref. 15 has not previously been digitized. This publication contains data hitherto poorly accessible to the scientific community, and which has not been rigorously interrogated. Additionally, GC Topt and Tmax data were extracted for 107 Phytophthora species from ref. 20, hereafter referred to as the ‘Martin dataset’. Finally, IN cardinal temperature for 44 plant pathogen species were extracted from ref. 44, hereafter referred to as the ‘Magarey dataset’.

The Index Fungorum (IF) and associated Species Fungorum (SF) databases (www.indexfungorum.org; www.speciesfungorum.org) were used to identify current synonyms for each species recorded in the Togashi dataset (accessed between 8/5/2020 and 15/5/2020). Where no current name was available, or species authorship name(s) were very inconsistent (i.e. no similarity to that cited in ref. 15), the Mycobank database (www.mycobank.org) was used as an alternative (accessed between 8/5/2020 and 15/5/2020). Species were recorded by their current name, according to the IF/SF or Mycobank databases (as above). Where no current name was explicitly provided, but the species could be identified, the species name searched and located was assumed to be current and correct. However, such records were treated as ambiguous. Similarly, if a species could be identified but species authorship name(s) cited in ref. 15 showed no similarity to that on the IF/SF and/or Mycobank databases, or where species authorship name(s) were not provided by ref. 15, the species was included but treated as ambiguous. Where spelling of species names differed between ref. 15 and the IF/SF and/or Mycobank databases, but it was possible that the spelling in ref. 15 was an error, species names were updated to reflect this, but treated as ambiguous. If a species cited in ref. 15 could not be identified at all on the IF/SF or Mycobank databases (i.e. where no synonymous names assigned by ref. 15 could be identified), it was excluded from the dataset, except in a few cases, where alternative resources were used to cross-reference species names (see Togashi dataset for further details). In some cases, species were recorded in ref. 15 under multiple synonyms. However, said species were at times found to be not synonymous, once identified in the IF/SF and/or Mycobank databases. Various methods were used to correct for this, detailed below.

If cardinal temperature data in ref. 15 specifically referred to one of the nonsynonymous species, these were recorded under the currently designated name for that species on the IF/SF or Mycobank databases (as explained above). For example, GC cardinal temperature data were recorded for Fusarium sambucinum (Fuck.) [syn. Fusarium discolour var. sulphureum (App. et Wr.), Fusarium polymorphum (Mart.), Fusarium roseum (Lk.), Fusarium sulphureum (Schlecht)]. The IF/SF database classified F. sambucinum as F. roseum Link (1890) but F. sulphureum as F. sulphureum Schltdl. (1824). However, a subset of cardinal temperature data in ref. 15 were recorded “as sulphureum”, and so were assigned to F. sulphureum, and not F. roseum in the Togashi dataset. In contrast, if cardinal temperature data associated with multiple, nonsynonymous species did not explicitly specify which species the data referred to, two alternative methods were used for clarification. First, the titles of publications cited in ref. 15 for that species record were cross-referenced, to determine if a species name (or disease name that likely suggested a species) was provided in the title. If so, species names were corrected to match that of the publication title, for that data point. For example, GC cardinal temperature data were recorded by ref. 15 for Corticium vagum (Berk. et Curt.) [syn. Rhizoctonia solani (Kühn)]. The IF/SF databases classified the former as Botryobasidium vagum ((Berk. & M.A. Curtis) D.P. Rogers (1935)), but the latter as R. solani (J.G. Kühn, (1858)). A subset of titles from publications used by ref. 15 to extract cardinal temperature data contained the term “Rhizoctonia solani”, and so such data were here assigned to R. phaseoli, and not B. vagum. However, if no usable information was provided in publication titles, data were here recorded under the first species given by ref. 15. This name was chosen as it was the bold, title name given to that species record in ref. 15. For example, in ref. 15 GC cardinal temperature data were recorded for Fusarium redolens (Wr.) [syn. Fusarium reticulatum (Mont.); Fusarium spinaciae (Sherb.)]. The IF/SF databases classified neither F. reticulatum nor F. spinaciae as synonymous with F. redolens. However, it was not clear in ref. 15 which cardinal temperatures referred to which species, and titles of publications used to extract cardinal temperature data by ref. 15 only stated “Fusarium”. Hence, all data were here recorded under the bold, title species name—F. redolens. Any records that underwent additional processing outlined here were also deemed ambiguous. Any synonyms assigned by ref. 15 that could not be identified were deemed nonsynonymous. Where species in ref. 15 were recorded under multiple species names, that were here found to be synonymous, we assumed all publications used by ref. 15 to extract cardinal temperature data refer only to these species.

All cardinal temperature data concerning Fusarium oxysporum formae speciales were recorded under F. oxysporum, as well as their respective formae speciales. These formae speciales were excluded from analyses of within-species cardinal temperature analyses (Fig. 2, Supplementary Tables 2–4, 6, 7), but were included in analyses of niche co-specialization (Fig. 3, Supplementary Tables 5, 8–10), thereby maintaining specific known pathogen–host interactions in the latter analysis.

The methods of determining fungi and oomycete species names resulted in cardinal temperature data for 695 microbes (631 fungi and 64 oomycetes, N = 8656) being recorded in the Togashi dataset. Previous analyses of thermal responses have considered only a handful of fungi and no oomycetes35,45,46. When data of ambiguous species records (explained above) were excluded, 568 microbes (514 fungi and 54 oomycetes, N = 6045) remained in the Togashi dataset. Excluding ambiguous species records had little influence on our results (Supplementary Tables 6, 8). All information regarding how species were named in the Togashi dataset, including species authorship name(s) cited in ref. 15 and the various databases detailed above, changes to spelling of species names cited in ref. 15, apparent synonymous and nonsynonymous species names cited in ref. 15, cases where data were extracted from one species record and recorded as a different species, and species records treated as ambiguous, can be found in the Togashi dataset.

For each data point recorded in the Togashi dataset, where ref. 15 recorded that the true value lies above or below the value provided, the value provided was recorded. For example, if Tmin was recorded as ‘below 8 °C’, 8 °C was recorded as Tmin; if Tmax was recorded as ‘above 25 °C’, 25 °C was recorded as Tmax. Where a range was provided, the mid-point was recorded. However, where a range was provided, but the true value was recorded to lie above or below this, the upper or lower limit was chosen, respectively. For example, if Tmin was quoted as ‘below 18–20 °C’, 18 °C was recorded as Tmin. Where a range was quoted for the entire biological process, the upper and lower bounds were recorded as Tmax and Tmin, respectively. For example, if IN was quoted as ‘occurring between 5 and 35 °C’, 5 °C was recorded as Tmin and 35 °C was recorded as Tmax. However, in cases where it was likely that the temperature range quoted referred to a range of optimal conditions, the mid-point was recorded as Topt unless stated otherwise. Cardinal temperatures were also estimated from prose in ref. 15. Data under ‘IN and DD’ were independently recorded under IN and DD, unless the text specifically indicated one of these processes. Data recorded as ‘Specialization and resistance” were recorded under IN and/or DD, where appropriate. Data quoted in ref. 15 that were the result of complex treatments and/or were not likely related to Tmin, Topt, or Tmax were excluded. Further information regarding how each cardinal temperature data point in the Togashi dataset was determined from information provided in ref. 15 is reported in the Togashi dataset. Where multiple references were provided for a single data point in ref. 15, this was taken to represent independent observations, and so were individually included in the Togashi dataset. All data extraction was completed by the same researcher. For the Magarey dataset, cardinal temperatures were recorded as point estimates and pathogen names were updated according to the IF/SF database or Mycobank database (accessed between 8/5/2020 and 15/5/2020) to ensure correct matching to the Togashi dataset for data validation (see below). Finally, for each data point recorded in the Martin dataset, where ref. 20 recorded that the true value lies above or below the value provided, the value provided was recorded, and where a range was provided, the mid-point was recorded. To ensure maximum matching to Phytophthora species phylogenies (detailed below), Phytophthora katsurae was renamed Phytophthora castaneae in the Martin dataset. We also assumed that Phytophthora ipomoea corresponded to Phytophthora ipomoeae.

Data analysis

All analyses were performed in R 3.5.347. In all analyses the means of Tmin, Topt or Tmax for a given biological process, for a given species, were treated as a single data-point. Where more than five related statistical tests were conducted (Supplementary Tables 2, 5, 7, and 10) the Holm–Bonferroni correction48 for multiple tests was applied, with adjusted significance levels given in table legends.

Data validation

Sixteen pathogens were recorded in both the Togashi and Magarey datasets. For these species, root mean square error (RMSE) was calculated between IN cardinal temperature estimates. When all data were included, RMSE was 5.15 °C (N = 43) (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Clustering of data points at 35 and 1 °C along the y-axis is a result of how ref. 44 estimated Tmax and Tmin, respectively—if no Tmax for IN was found, the authors set Tmax to 35 °C. Similarly, if no Tmin for IN was found, but IN could occur lower than the hosts developmental threshold, the authors set Tmin to be 5 °C lower than the lowest tested temperature, but not lower than 1 °C. When Tmin data recorded as 1 °C and Tmax data recorded as 35 °C in the Magarey dataset were excluded, RMSE was 4.73 °C (N = 29) (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The greatest deviation from an identity relationship (dotted line) occurred around Tmin (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). This may be due to Tmin being more problematic to quantify—the lowest temperature a given biological process occurs at will depend on the amount of time given for the process to occur. Tmax is likely to be more clearly defined as cells will die at high temperature. Further, 22 Phytophthora species were present in both the Togashi and Martin datasets. For these pathogens, RMSE was calculated for GC Topt as 2.65 °C (N = 20) (Supplementary Fig. 3c) and GC Tmax as 3.34 °C (N = 22) (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Where multiple, independent cardinal temperature estimates were cited for the same species the mean was taken for all analyses above. Abstracting cardinal temperatures for GC from ref. 15 was straightforward because data were mostly tabulated. In contrast, DD and IN data in ref. 15 were more often written in prose (see the Togashi dataset for further details). This is one possible explanation for the greater calculated RMSE for IN than GC.

Analysis of cardinal temperature

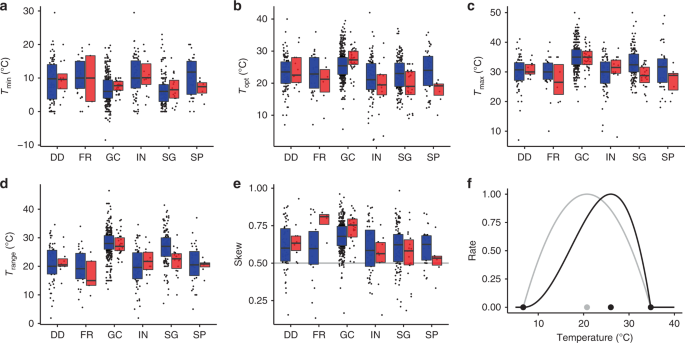

The Togashi dataset was used for this analysis. Where multiple, independent cardinal temperature estimates were cited for the same species and biological process in ref. 15, the mean was taken. Supplementary Data 1 provides summary information regarding species–biological process–cardinal temperature sample sizes for the Togahsi dataset. Trange was calculated as the range between Tmin and Tmax. Trange0.5 was calculated as the range between Tmin0.5 and Tmax0.5; Tmax0.5 and Tmin0.5 refer to Tmax and Tmin where a species response rate = 0.5 (at Topt the responses = 1, at Tmin and Tmax the response = 0). Hence, Trange0.5 reflects the temperature range where a species performs a biological process well. Responses were calculated by a beta function (Eq. (1)) that uses a species’ cardinal temperature to estimate a temperature performance curve16. Skew was calculated according to Eq. (2), Where skew >0.5, Topt is closer to Tmax than Tmin; where skew <0.5, Topt is closer to Tmin than Tmax. Species with at least one Topt, Trange or skew estimate were included in analyses involving Topt, Trange and skew, respectively.

$$rleft( T right) = left( {frac{{T_{{mathrm{max}}} – T}}{{T_{{mathrm{max}}} – T_{{mathrm{opt}}}}}} right)left( {frac{{T – T_{{mathrm{min}}}}}{{T_{{mathrm{opt}}} – T_{{mathrm{min}}}}}} right)^{left( {T_{{mathrm{opt}}} – T_{{mathrm{min}}}} right)/left( {T_{{mathrm{max}}} – T_{{mathrm{opt}}}} right)}$$

(1)

$$;{mathrm{skew}} = frac{{T_{{mathrm{opt}}} – T_{{mathrm{min}}}}}{{T_{{mathrm{max}}} – T_{{mathrm{min}}}}}qquadqquadqquadqquadqquadqquadqquadqquad$$

(2)

In some cases, for particular species–biological process combinations, mean Topt was estimated as greater than mean Tmax or lower than mean Tmin. This is because data from multiple, independent sources were provided within ref. 15. For such cases, nonsensical values (i.e. skew <0 or >1) were removed for these species–biological process combinations. Differences between cardinal temperatures for GC and other processes were compared within species using two-sided t-tests (Supplementary Table 2). Association between GC Topt and Topt of other biological processes was investigated using two-sided Pearson correlation (Supplementary Table 3). The same analysis was performed for Trange (Supplementary Table 4). Sample size varies in the Togashi dataset as a species may have a Tmin, Topt and/or Tmax estimate for one biological process, but not others.

Niche co-specialization

The Togashi dataset was used for this analysis. The Plantwise database (CABI) (accessed 28/10/2013, by permission) provides information on known pathogen/host interactions. To improve matching of pathogen species between the Togashi dataset and the Plantwise database, 85 pathogen species names were updated in the Plantwise database (Supplementary Table 11), according to their respective, current names given in the IF/SF and/or Mycobank databases [accessed between 8/5/2020 and 15/5/2020]. As above, Mycobank was used where no information was available on IF/SF. Species authorship names are not recorded in the Plantwise database and so were not considered here. Hence, it was assumed that if any alternative current name for a pathogen in the Plantwise database was present in the Togashi dataset, it was a correct match. Sensu species names recorded in the IF/SF and Mycobank databases were also included during this matching process. Authorship names of current species were cross-checked to the Togashi database, to ensure current species were a true match.

All recorded plant hosts of fungi and oomycetes included in the Togashi dataset were identified. Host variety was not considered (i.e. hosts were recorded no further than species rank). Peronospora farinosa was assigned all hosts recorded for P. farinosa, as well as those recorded for P. farinose formae speciales in the Plantwise database. Similarly, F. oxysporum was assigned all hosts recorded for F. oxysporum, as well as those recorded for F. oxysporum formae speciales. F. oxysporum formae speciales were also included in this analysis as individual data points due to formae speciales cardinal temperature data available in the Togashi dataset. Two different methods were used to quantify host diversity of pathogens. First, only hosts recorded to species level in the Plantwise database were included. In this case, 1016 hosts of 302 pathogens were utilized to generate a time-calibrated host phylogeny using the R function ‘S.PhyloMaker’ (scenario 1, genera or species added as basal polytomies within their families or genera)49. The resultant generated host phylogeny is hereafter referred to as the ‘unprocessed host phylogeny’ (Supplementary Fig. 4). Second, where a host record in the Plantwise database was not identified to species, it was assumed that the pathogen in question was able to successfully infect all species present in S.PhyloMaker, within the taxonomic rank reported. For example, Macrophomina phaseolina was recorded in the Plantwise database as being a pathogen of the class Pinopsida. Hence, 419 host species found within the class Pinopsida in S.PhyloMaker were added to M. phaseolina host range. S.PhyloMaker did not report above family classification. Hence, we assumed that pathogens reported to infect class Pinopsida included the families Araucariaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, Cupressaceae, Pinaceae, Podocarpaceae, Sciadopityaceae, and Taxaceae, and to infect order Gentianales included the families Apocynaceae, Gelsemiaceae, Gentianaceae, Loganiaceae, and Rubiaceae. In this case, 15,982 hosts of 309 pathogens were used to generate a time-calibrated host phylogeny, also using the R function ‘S.PhyloMaker’ (scenario 1)49. The resultant generated host phylogeny is hereafter referred to as the ‘processed host phylogeny’ (Supplementary Fig. 5). To improve correct matching of plant host species names to S.PhyloMaker or improve positioning of species during phylogeny construction, some corrections to host species names in the Plantwise database were made, according to The Plant List (TPL) (www.theplantlist.org) (accessed between 19/3/2020 and 16/5/2020) (Supplementary Table 12). First, hosts species in the Plantwise database that were not identifiable to genus-level in S.PhyloMaker were corrected, where possible. Second, hosts not identifiable to species-level in S.PhyloMaker were then corrected, where possible. This method ensured that during phylogeny construction (1) all hosts species included in the analysis were identifiable to at least genus-level in S.PhyloMaker and (2) we maximized the number of host species identified to species-level. In all cases, author or publication details of host species names was not considered, as this information was not provided in the Plantwise database. Hence, if multiple accepted names were provided by TPL, the following method was applied. First, if any of the accepted species name given by TPL were identical to that given by the Plantwise database, this name was given. Second, if none of the accepted species names given by TPL were identical to the Plantwise database, a single TPL-accepted species name was selected at random for that host. Seven hosts species (Abelmoschus esculentus, Cyphomandra betacea, Cuprocyparis leylandii, Elettaria cardamomum, Gloriosa rothschildiana, Coleus forskohlii, and Ullucus tuberosus) as well as the genus-level records Ascocenda, Elettaria, and Scindapsus were not identifiable to genus-level in S.PhyloMaker, and hence were excluded from the analysis. This was due to uncertainty in classification and phylogenetic position, or seemingly missing data in S.PhyloMaker. Further information is provided in Supplementary Table 9.

The function ‘pd’ in the R package ‘picante’50 was used to quantify host diversity of each pathogen. Host diversity was calculated as Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (PD)51. The phylogeny root node was excluded in all calculations. Hence, pathogens with a single host were assigned a PD of zero. Fewer pathogens were included for analyses involved Trange0.5 as this parameter required estimates of Tmin and Tmax, as well as Topt. Co-specialistion across abiotic (Trange or Trange0.5) and biotic (log10+1-transformed host diversity) niche axes was calculated by two-sided Pearson correlation.

Cardinal temperature phylogenetic signal

The Martin dataset was used for this analysis. Phylogenies constructed by (1) Bayesian, (2) maximum likelihood, and (3) maximum parsimony methods for Phytophthora species were extracted from ref. 19 (TreeBASE S19303). 101 Phytophthora species (P. alni (Topt and Tmax calculated as the average of P. alni sub. sp. alni, P. alni sub. sp. multiformis, and P. alni sub. sp. uniformis in ref. 20), P. alticola, P. andina, P. aquimorbida, P. arenaria, P. austrocedrae, P. bisheria, P. boehmeriae, P. botryose, P. brassicae, P. cactorum, P. cajani, P. cambivora, P. capensis, P. capsici, P. captiosa, P. castaneae, P. chrysanthemi, P. cinnamomi, P. citricola, P. citrophthora, P. clandestina, P. colocasiae, P. constricta, P. cryptogea, P. drechsleri, P. elongata, P. erythroseptica, P. europaea, P. fallax, P. fluvialis, P. foliorum, P. fragariae, P. frigida, P. gallica, P. gemini, P. gibbosa, P. glovera, P. gonapodyides, P. gregata, P. hedraiandra, P. heveae, P. hibernalis, P. humicola, P. hydropathica, P. idaei, P. ilicis, P. infestans, P. inflata, P. insolita, P. inundata, P. ipomoeae, P. iranica, P. irrigata, P. kernoviae, P. lateralis, P. litoralis, P. macrochlamydospora, P. meadii, P. medicaginis, P. megakarya, P. megasperma, P. melonis, P. mengei, P. mexicana, P. mirabilis, P. morindae, P. multivesiculata, P. multivora, P. nemorosa, P. nicotianae, P. obscura, P. palmivora, P. parsiana, P. phaseoli, P. pini, P. pinifolia, P. pistaciae, P. plurivora, P. polonica, P. primulae, P. pseudosyringae, P. pseudotsugae, P. psychrophila, P. quercetorum, P. quercina, P. quininea, P. ramorum, P. richardiae, P. rosacearum, P. rubi, P. sansomeana, P. siskiyouensis, P. sojae, P. syringae, P. tentaculata, P. thermophila, P. trifolii, P. tropicalis, P. uliginosa, and P. vignae) were present in both the Martin dataset and extracted phylogenies. We assumed that Phytophthora x alni recorded in ref. 19 corresponded to Phytophthora alni. The function ‘phylosig’ in the R package ‘phytools’52 was used to separately test for a phylogenetic signal for GC Topt and Tmax (N = 101). 10,000 simulations were run in each analysis for randomization test. Where multiple strains of a particular Phytophthora species were included in a phylogeny, only one strain was assigned a GC Topt or Tmax record from the Martin dataset, thereby preventing pseudoreplication.

The influence of spatial autocorrelation on phylogenetic signal of Phytophthora species cardinal temperature was investigated (Supplementary Fig. 1). For 31 Phytophthora species included in the above analysis (P. alni, P. boehmeriae, P. botryosa, P. cactorum, P. cambivora, P. capsici, P. castaneae, P. cinnamomi, P. citrophthora, P. colocasiae, P. cryptogea, P. drechsleri, P. erythroseptica, P. fragariae, P. infestans, P. kernoviae, P. lateralis, P. macrochlamydospora, P. meadii, P. medicaginis, P. megakarya, P. megasperma, P. nicotianae, P. palmivora, P. pseudosyringae, P. quercetorum, P. quercina, P. ramorum, P. rubi, P. sojae, and P. vignae), estimates of presence at country or region scale were extracted from CABI Plantwise53,54. To maximize species matching between datasets, P. erythroseptica var. erythroseptica was renamed P. erythroseptica, P. drechsleri f.sp. cajani was renamed P. drechsleri, and P. katsurae was renamed P. castaneae in the Plantwise database.

The centroid of the country or region were used for all records. Mantel correlations (MCs) were performed between GC Topt (and Tmax) distance and great circle distance (km) or average air surface temperature (AST) distance (oC) matrices. Gridded average AST (January 1951 and December 1980) was extracted from Berkley Earth (www.berkeleyearth.org) (accessed 19/11/2017) for each latitude–longitude location. Latitude and longitudes values in the CABI Plantwise database were rounded to the nearest 1° interval, to align with those extracted from Berkley Earth for analysis of average air surface temperature distance.

All MC were performed using the function ‘mantel’ in the R package ‘ecodist’55 with 10,000 iterations to calculate bootstrapped confidence limits. P values were calculated according to a null hypothesis that MCs were equal to zero (two-tailed test).

Co-phylogenetic association

The Martin dataset was used for this analysis. 35 Phytophthora species were present in both the Plantwise database and extracted Phytophthora phylogenies detailed above (P. alni, P. asparagi, P. boehmeriae, P. botryose, P. cactorum, P. cambivora, P. capsica, P. castaneae, P. cinnamomi, P. citricola, P. citrophthora, P. colocasiae, P. cryptogea, P. drechsleri, P. erythroseptica, P. fragariae, P. hibernalis, P. infestans, P. kernoviae, P. lateralis, P. macrochlamydospora, P. meadii, P. medicaginis, P. megakarya, P. megasperma, P. nicotianae, P. palmivora, P. phaseoli, P. pseudotsugae, P. ramorum, P. richardiae, P. rubi, P. sojae, P. syringae, and P. vignae). To maximize species matching between datasets, P. erythroseptica var. erythroseptica was renamed P. erythroseptica, P. drechsleri f.sp. cajani was renamed P. drechsleri, and P. katsurae was renamed P. castaneae in the Plantwise database. As previously, we also assumed that Phytophthora x alni recorded in ref. 19 corresponded to Phytophthora alni. The 258 hosts of these pathogens recorded to species level in the Plantwise database were extracted (i.e. those only recorded to genus or family were excluded, and host variety was not considered) and utilized to generate a time-calibrated host phylogeny using the R function ‘S.PhyloMaker’ (scenario 1) (Supplementary Fig. 6). As above, to improve correct matching of plant species names to S.PhyloMaker, some corrections to host species names in the Plantwise database were made, according to The Plant List (TPL) (www.theplantlist.org) (accessed 19/3/2020) (Supplementary Table 12). 239 hosts matched to species level in S.PhyloMaker and 17 hosts matched to genus level. Two hosts (C. betacea and E. cardamomum) were not identifiable to genus-level in S.PhyloMaker, and hence were excluded from the analysis. The function ‘PACo’ in the R package ‘paco’56 was used to test for co-phylogenetic association between each Phytophthora species phylogeny and the generated host phylogeny (N = 35). We applied a square root correction to the patristic distance matrices calculated from the Phytophthora phylogenies due to negative eigenvalues57. Host and pathogen phylogenies were standardized prior to super-imposition, resulting in the best-fit of the superimposition being independent of both phylogenies57. Additionally, the method quasiswap was assigned, which is a more constrained method than others available, where the number of interactions is conserved for each species (and hence in the network as a whole). These methods were chosen because we make no assumption about which group (host or pathogen) is tracking the other57. 10,000 randomizations were run in each analysis. Under perfect co-phylogenetic association, the best-fit Procrustean super-imposition (m2XY) is zero. As co-phylogenetic association declines, m2XY tends towards that calculated in the ensemble of network randomizations in each null model. Where multiple strains of a particular Phytophthora species were included in a phylogeny, only one strain was assigned a host range, thereby preventing pseudo-replication.

Influence of uncertainty in reported cardinal temperatures

Cardinal temperature data in the Togashi and Martin datasets contain uncertainties due to reported values varying from their true values (i.e. Tmax < 32). We investigated whether these potential uncertainties could have affected our conclusions concerning fundamental vs. realized niche geometry, niche cospecialisation, and cardinal temperature phylogenetic signal. It was beyond the scope of this study to establish how cardinal temperatures were determined for each record reported in ref. 15. Further, ref. 20 does not provide information or references as to how reported Topt and Tmax were determined. To overcome this, we assumed that in all cases cardinal temperature was investigated experimentally at 5 °C increments, and that the minimum and maximum temperature treatments spanned Trange. This implies that on average cardinal temperature estimates do not deviate from their true values by more than ±2.5 °C. Hence, for both the Togashi and Martin datasets, 2.5 °C was added or subtracted from cardinal temperature data reported as being above or below their true value, respectively. For example, GC data reported as >25 °C was modified to 27.5 °C. Where data in the Togashi dataset were extracted from prose, data were modified in this way only if we could determine the direction of the error with confidence. In all cases, errors have little effect on our results and did not affect any of our key conclusions (Supplementary Tables 7, 10, and 13). This suggests that uncertainties are randomly distributed and do not affect the results presented here.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Source: Ecology - nature.com