Sites and study species

Both playback experiments (described below) took place in multiple wetlands in Champaign (n = 3), Iroquois (n = 1), and Vermilion counties (n = 3) in central Illinois, USA. Sites were comprised of mesic shrubland habitat, with dominant shrubs including willow (Salix spp.), dogwood (Cornus spp.), and Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellate), with mesic grasses abundant among shrubs. Patches of cattails (Typha spp.) and reed (Phragmites spp.) were prevalent along bodies of water at most sites50,51.

Redwings are sympatric with yellow warblers in Illinois, and both are parasitised by cowbirds48,49,52 (pers. obs.). At our sites, redwings arrive as early as February and nest from late-April through late-July, with peak breeding in late-May50,51 (pers. obs). Redwings are polygynous, and males may have several nests from different females on their territory34. Yellow warblers arrive at our sites late-April and breed from early-May through late June, with peak breeding mid-to-late-May. At these sites the interspecific overlap of territories was common between redwings and yellow warblers (pers. obs.).

Playback stimuli construction

For our experiments, we constructed playlists for six different playback treatments: (1) female cowbird chatters (brood parasite), (2) yellow warbler seet calls (cowbird-specific anti-parasitic alarm call17,18,19,30,42), (3) yellow warbler chip calls (general antipredatory alarm call47,53), (4) redwing chatters (general conspecific vocalization54), (5) blue jay calls (a warbler and redwing nest predator55), and (6) wood thrush songs (an innocuous heterospecific control that is sympatric with redwings but do not prey, parasitize, or compete with them56). We included blue jay calls to tease apart if redwings responded to seet calls as a general alarm call, or a referential alarm call specifically informing brood parasitism risk. Using both a brood parasite and predator call presentation is necessary to fully understand whether the host’s aggressive responses are specifically anti-parasitic or general57. The chip was chosen as a relevant general alarm stimulus for playbacks on yellow warbler territories, and redwing chatters were used as a relevant territory intrusion stimulus on redwing territories. Note that experiments 1 and 2 differed in which treatments were used (described below).

We used audio files from Xeno Canto, all sourced from the Midwestern and Southwestern United States (Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, and Ohio), except for seet calls, which were sourced directly from Gill and Sealy18, and redwing chatters, which were sourced from Lynch et al.58. Playlists were created using Adobe Audition CC 2019. To avoid pseudoreplication59, we constructed five different playlist files for each treatment, and chose one exemplar file randomly for each playback trial (described below). Each playlist was comprised of vocalizations from at least three different individuals. Vocalizations from individuals were placed in a random order, and then repeated to obtain the 10-min playlist. Intervals of silence were placed into between vocalizations, with intervals ranging from 2 to 6 s based on rates found in natural recordings on Xeno Canto. Amplitude was adjusted such that sounds played from our speaker at full volume were ~90 dB (measured 0.5 m from speaker). To minimize signal-to-noise ratio in playback files, frequencies below 500 Hz, which are well below the range of any of our stimuli, were filtered out.

For both experiments, playbacks were conducted with an AYL-SoundFit speaker connected to a Samsung Galaxy 8 cellular phone with the audio files. We placed equipment ~1 m high in vegetation and recorded data from > 10 m away. Playback trials occurred for 10 min. For both experiments, we retested each territory 24–72 h later (mean = 41) to avoid habituation, with a different, randomly assigned treatment to prevent order effects. All statistical tests were conducted in the statistical program R 3.6.1 (packages lme4, nlme, multcomp, emmeans and car; see “Statistical analyses” section), with α = 0.05.

These studies were approved by the animal ethics committee (IACUC) of the University of Illinois (#17259), and by USA federal (MB08861A-3) and Illinois state agencies (NH19.6279).

Experiment 1: playback on yellow warbler territories

Playback experiment: To assess if redwings respond similarly to cowbird chatters and seet calls, but not to other yellow warbler or heterospecific calls, we first used data collected during playback trials at active yellow warbler territories. Warbler territories were determined to be active in two ways: (1) if a nest with eggs was found on the territory, (2) if a nest could not be found but both a male and female were present on the territory on checks across multiple days and the pair produced alarm calls at the experimenter, which is indicative of nesting investment on the territory54 (pers. obs.). We also excluded any yellow warbler pairs seen carrying nesting material or insects, which signify building and nestling stage, respectively. Seet calls are almost exclusively produced during laying and incubation stage33,47, thus we only presented playbacks on territories presumed to be in those stages. Yellow warbler playbacks trials occurred from mid-May to late June in 2018 and 2019, and between 0500 and 1200 h local time. We did not systematically band territorial birds at our sites for individual identification prior to experimentation. Therefore, all nests tested were ≥ 30 m apart to maintain independence, as nests at this distance likely belong to different breeding units based on average territory size50,60,61. In addition, we waited 30–60 min between playbacks at neighboring sites to avoid any carryover effects on neighbors.

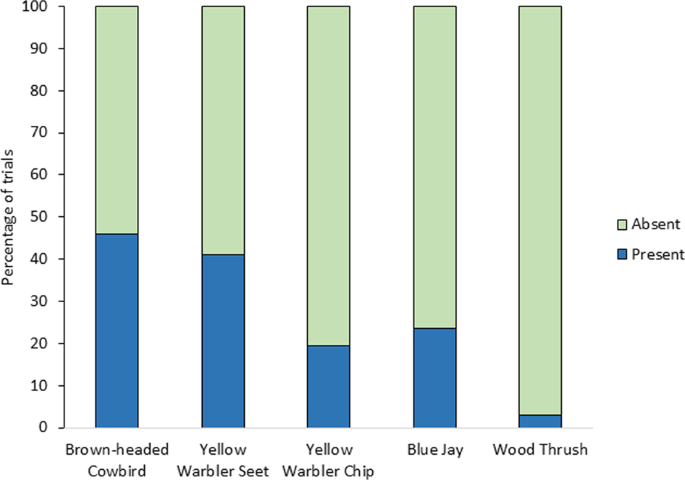

Yellow warbler territories received one of five different playback treatments on two separate days, such that each territory was tested with two of the five playback types. Playbacks included cowbird chatters (n = 37), yellow warbler seets (n = 34), yellow warbler chips (n = 31), blue jay calls (n = 34), and wood thrush songs as an innocuous heterospecific control (n = 35), for a total of 171 playbacks. The playback speaker was placed 5–6 m from the yellow warbler male’s commonly used song post. During this set of initial playback trials, we specifically recorded a single binary response variable of whether any redwings responded to the playback or not. A response was only marked if one or more male redwings were present and alarm calling within 30 m (radial average distance of territory size56) of the speaker any time during the 10-min playback. Redwing alarm calls are described in Knight and Temple54. We also report on which other species, apart from yellow warblers, responded to these same playback types during this experiment (see Supplementary Table 4).

Experiment 2: playback on red-winged blackbird territories and at nests

Playback experiment: To investigate if territorial redwings respond to seet calls to enhance their frontloaded nest defenses against cowbirds, we conducted playback trials at active redwing nests in 2018 and 2019. Playbacks were conducted using the same methodology and site locations in Champaign and Vermillion counties as Experiment 1. In Experiment 2, we increased the distance at which nests/song posts were tested, to maintain independence, to ≥50 m apart, as average territory size is larger for redwings than yellow warblers34. This distance also prevented us from inadvertently testing the same parents twice at different nests, as redwings are polygynous harem breeders within their territories34. Playbacks in 2018 were conducted 5 m from the male’s focal song post. We were unable to search for nests in 2018, but used behavioral observations to select pairs that likely had an active nest (e.g., alarm calling, no nest material carried or fledglings present). In 2019, we instead placed speakers 5 m from known, located active nests and conducted playbacks during the incubation stage, as this is when cowbirds pose the gravest threat62. In 2019, we conducted playbacks with speakers 5 m from focal nests, instead of song posts to reliably simulate the threats to the nest. We thoroughly searched sites 1–2 times weekly for active nests. Nest contents were checked every 3 days to ensure playback trials occurred during incubation.

Similar to experiment 1, redwings received one of five different playback treatments on 2 separate days, such that each pair was tested with two of the five playbacks: cowbird chatters (n = 5 in 2018; n = 18 in 2019), yellow warbler seets (n = 5 in 2018; n = 13 in 2019), redwing chatters (n = 9 in 2018, n = 16 in 2019), blue jay calls (n = 0 in 2018; n = 16 in 2019), and wood thrush songs (n = 6 in 2018; n = 17 in 2019), for a total of 105 playbacks across 2 years. In 2019, two nests were not retested as they were depredated between trials. For logistical reasons, we did not include blue jay calls in 2018. Only male responses were recorded in 2018 because only males responded to the playbacks on yellow warbler territories. After noting that females responded as well near known active nests, we also recorded responses for both sexes in 2019 (see “Statistics and reproducibility” below).

During the playback trial, we recorded the following behavioral responses from the target individual within 30 m of the speaker: (1) response latency (sec after the start of trial when a switch to aggressive behaviors occurred: posturing, hopping, alarm calling, or attacking the speaker); (2) closest approach to the speaker (m); and (3) call rate (total calls/10 min). In 2018, we only counted “checks” and “cheers” as these are general alarm calls used by redwings in many contexts63. In 2019, we expanded to counting “checks”, “chits”, “chonks”, and “cheers” as they are all used interchangeably as nest defense alarm calls by both sexes, although only males produce cheer calls54,63,64. Therefore, we analyzed call rate for 2018 and 2019 separately.

Calling rate analysis across distances between heterospecific territories

We used spatial data to evaluate if redwings nesting closer to yellow warbler territories mount stronger responses (calls) to playbacks of cowbird chatters and seet calls than redwings nesting farther away that do not access to the heterospecific hosts’ signal. In 2019, we recorded locations of playbacks conducted at known, active redwing nests and yellow warbler territories using GPS units with 3 m accuracy (Garmin eTrex 10). Using software in ArcGIS (ver 10.4 ESRI), we measured the distance (m) of each redwing nest to the nearest playback conducted on a yellow warbler territory. We assumed that we found all active redwing nests and warbler territories within these study subsites. Prior work37 found that redwings would respond to playbacks up to 60 m from the nest, which coincided with the redwings’ territory boundaries. Many of our territories in marginal, upland habitats were larger than the reported average, so we extended our cutoff range to count redwing nests that were up to 75 m away from a yellow warbler territory. If redwings were deriving any benefit from eavesdropping on cowbird danger as predicted by chatters and seets, then they would need to nest within this range from a yellow warbler nest to be able to eavesdrop on and respond to their neighbor’s seets.

Statistics and reproducibility

Experiment 1: playback on yellow warbler territories: We ran a nominal logistic regression that analyzed the effect of playback treatment on whether redwings were absent or present during trials. We then ran post hoc Tukey pairwise comparisons between cowbird vs seet treatments, seet vs wood thrush, and seet vs chip treatments to account for multiple comparisons between playback type pairs.

Experiment 2: playback on red-winged blackbird territories and at nests: We evaluated whether playback treatment affected the three response variables of interest (latency, total alarm calls, and closest approach) using a separate model for each. For latency and approach, we combined the data from 2018 and 2019, but for call rates, we analyzed data separately for the two years because some call types were not counted in 2018 and only males were recorded that year (see above). We determined if redwing (males and females separately) responded immediately (latency of <1 s) or with some latency (≥1 s) and conducted a χ2 test on the ratios by treatment to determine if birds were more likely to respond immediately during particular playback treatments. We also ran a negative binomial generalized mixed model on the nonzero response latencies (# of seconds to respond) with playback treatment and date as fixed effects, and redwing nest site ID as a random effect. For alarm call and closest approach variables, we log transformed the data after adding a small constant and ran general linear mixed models. In each model, we included playback treatment and date as fixed effects, and redwing nest site ID as a random effect. For all three models, we ran post hoc Tukey tests to multiple compare treatment pairs of least-square means.

Calling rate analysis across distances between heterospecific territories

We ran separate analyses of variance for males and females, which analyzed calling rate (calls per min) during seet and cowbird playbacks with distance from the focal redwing’s nest to the nearest yellow warbler territory and the playback call treatment (seet vs. chatter) as fixed effects.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Source: Ecology - nature.com