Strand, D. W., Franco, O. E., Basanta, D., Anderson, A. R. A. & Hayward, S. W. Perspectives on tissue interactions in development and disease. Curr. Mol. Med. 10, 95–112 (2010).

Simon-Assmann, P., Spenle, C., Lefebvre, O. & Kedinger, M. The role of the basement membrane as a modulator of intestinal epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 96, 175–206 (2010).

Parmar, H. & Cunha, G. R. Epithelial–stromal interactions in the mouse and human mammary gland in vivo. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 11, 437–458 (2004).

Sugimoto, H., Mundel, T. M., Kieran, M. W. & Kalluri, R. Identification of fibroblast heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Biol. Ther. 5, 1640–1646 (2006).

Orimo, A. et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell 121, 335–348 (2005).

Tuxhorn, J. A., Ayala, G. E. & Rowley, D. R. Reactive stroma in prostate cancer progression. J. Urol. 166, 2472–2483 (2001).

Tuxhorn, J. A., McAlhany, S. J., Dang, T. D., Ayala, G. E. & Rowley, D. R. Stromal cells promote angiogenesis and growth of human prostate tumors in a differential reactive stroma (DRS) xenograft model. Cancer Res. 62, 3298–3307 (2002).

Ayala, G. et al. Reactive stroma as a predictor of biochemical-free recurrence in prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 4792–4801 (2003).

Olumi, A. F. et al. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 59, 5002–5011 (1999).

Franco, O. E. et al. Altered TGF-β signaling in a subpopulation of human stromal cells promotes prostatic carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 71, 1272–1281 (2011).

Kiskowski, M. A. et al. Role for stromal heterogeneity in prostate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 71, 3459–3470 (2011).

Bremnes, R. M. et al. The role of tumor stroma in cancer progression and prognosis: emphasis on carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 6, 209–217 (2011).

Tuxhorn, J. A. et al. Reactive stroma in human prostate cancer: induction of myofibroblast phenotype and extracellular matrix remodeling. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 2912–2923 (2002).

Levesque, C. & Nelson, P. S. Cellular constituents of the prostate stroma: key contributors to prostate cancer progression and therapy resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 8, a030510 (2018).

Yanagisawa, N. et al. Reprint of: Stromogenic prostatic carcinoma pattern (carcinomas with reactive stromal grade 3) in needle biopsies predicts biochemical recurrence-free survival in patients after radical prostatectomy. Hum. Pathol. 39, 282–291 (2008).

Diaz De Vivar, A. et al. Histologic features of stromogenic carcinoma of the prostate (carcinomas with reactive stroma grade 3). Hum. Pathol. 63, 202–211 (2017).

Ayala, G. E. et al. Determining prostate cancer-specific death through quantification of stromogenic carcinoma area in prostatectomy specimens. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 79–87 (2011).

San Martin, R. et al. Recruitment of CD34+ fibroblasts in tumor-associated reactive stroma: the reactive microvasculature hypothesis. Am. J. Pathol. 184, 1860–1870 (2014).

Potosky, A. L. et al. Five-year outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: the prostate cancer outcomes study. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 96, 1358–1367 (2004).

Penson, D. F. et al. General quality of life 2 years following treatment for prostate cancer: what influences outcomes? Results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 1147–1154 (2003).

Pound, C. R. et al. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA 281, 1591–1597 (1999).

Han, M., Partin, A. W., Pound, C. R., Epstein, J. I. & Walsh, P. C. Long-term biochemical disease-free and cancer-specific survival following anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. The 15-year Johns Hopkins experience. Urol. Clin. North Am. 28, 555–565 (2001).

Roehl, K. A., Han, M., Ramos, C. G., Antenor, J. A. & Catalona, W. J. Cancer progression and survival rates following anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy in 3,478 consecutive patients: long-term results. J. Urol. 172, 910–914 (2004).

Hull, G. W. et al. Cancer control with radical prostatectomy alone in 1,000 consecutive patients. J. Urol. 167, 528–534 (2002).

Amling, C. L. et al. Long-term hazard of progression after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: continued risk of biochemical failure after 5 years. J. Urol. 164, 101–105 (2000).

Moul, J. W. Treatment of PSA only recurrence of prostate cancer after prior local therapy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 12, 785–798 (2006).

Harrington, S., Lee, J., Colon, G. & Alappattu, M. Oncology section EDGE task force on prostate cancer: a systematic review of outcome measures for health-related quality of life. Rehabil. Oncol. 34, 27–35 (2016).

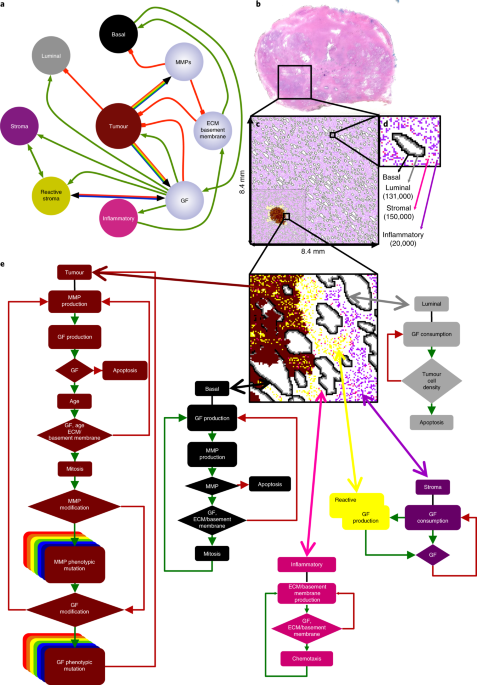

Basanta, D. et al. The role of transforming growth factor-β-mediated tumor–stroma interactions in prostate cancer progression: an integrative approach. Cancer Res. 69, 7111–7120 (2009).

Basanta, D. et al. Investigating prostate cancer tumour–stroma interactions: clinical and biological insights from an evolutionary game. Br. J. Cancer 106, 174–181 (2012).

Flach, E. H., Rebecca, V. W., Herlyn, M., Smalley, K. S. M. & Anderson, A. R. A. Fibroblasts contribute to melanoma tumor growth and drug resistance. Mol. Pharm. 8, 2039–2049 (2011).

Kim, E. et al. Senescent fibroblasts in melanoma initiation and progression: an integrated theoretical, experimental, and clinical approach. Cancer Res. 73, 6874–6885 (2013).

Araujo, A., Cook, L. M., Lynch, C. C. & Basanta, D. An integrated computational model of the bone microenvironment in bone-metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 74, 2391–2401 (2014).

Picco, N., Sahai, E., Maini, P. K. & Anderson, A. R. Integrating models to quantify environment-mediated drug resistance. Cancer Res. 77, 5409–5418 (2017).

Kaznatcheev, A., Peacock, J., Basanta, D., Marusyk, A. & Scott, J. G. Fibroblasts and alectinib switch the evolutionary games played by non-small cell lung cancer. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 450–456 (2019).

Kim, Y. & Othmer, H. G. A hybrid model of tumor–stromal interactions in breast cancer. Bull. Math. Biol. 75, 1304–1350 (2013).

Martin, N. K., Gaffney, E. A., Gatenby, R. A. & Maini, P. K. Tumour–stromal interactions in acid-mediated invasion: a mathematical model. J. Theor. Biol. 267, 461–470 (2010).

McKenney, J. K. et al. Histologic grading of prostatic adenocarcinoma can be further optimized: analysis of the relative prognostic strength of individual architectural patterns in 1275 patients from the canary retrospective cohort. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 40, 1439–1456 (2016).

Quaranta, V., Weaver, A. M., Cummings, P. T. & Anderson, A. R. A. Mathematical modeling of cancer: the future of prognosis and treatment. Clin. Chim. Acta 357, 173–179 (2005).

Anderson, A. R. A. A hybrid mathematical model of solid tumour invasion: the importance of cell adhesion. Math. Med. Biol. 22, 163–186 (2005).

Rejniak, K. A. & Anderson, A. R. A. Hybrid models of tumor growth. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 3, 115–125 (2011).

Raman, D., Baugher, P. J., Thu, Y. M. & Richmond, A. Role of chemokines in tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 256, 137–165 (2007).

Grivennikov, S. I., Greten, F. R. & Karin, M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140, 883–899 (2010).

Fluge, Ø. et al. Expression of EZH2 and Ki-67 in colorectal cancer and associations with treatment response and prognosis. Br. J. Cancer 101, 1282–1289 (2009).

Ao, M. et al. Cross-talk between paracrine-acting cytokine and chemokine pathways promotes malignancy in benign human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 67, 4244–4253 (2007).

Maru, N., Ohori, M., Kattan, M. W., Scardino, P. T. & Wheeler, T. M. Prognostic significance of the diameter of perineural invasion in radical prostatectomy specimens. Hum. Pathol. 32, 828–833 (2001).

Li, R. et al. Prognostic value of Akt-1 in human prostate cancer: a computerized quantitative assessment with quantum dot technology. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 3568–3573 (2009).

Li, R. et al. High level of androgen receptor is associated with aggressive clinicopathologic features and decreased biochemical recurrence-free survival in prostate: cancer patients treated with radical prostatectomy. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 28, 928–934 (2004).

Altman, D. G., Lausen, B., Sauerbrei, W. & Schumacher, M. Dangers of using “optimal” cutpoints in the evaluation of prognostic factors. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 86, 829–835 (1994).

Dakhova, O. et al. Global gene expression analysis of reactive stroma in prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 3979–3989 (2009).

Hayashi, N. & Cunha, G. R. Mesenchyme-induced changes in the neoplastic characteristics of the Dunning prostatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 51, 4924–4930 (1991).

Wheeler, T. M. & Lebovitz, R. M. Fresh tissue harvest for research from prostatectomy specimens. Prostate 25, 274–279 (1994).

Therneau, T. M. & Grambsch, P. M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model (Springer, 2000).

Grønnesby, J. K. & Borgan, Ø. A method for checking regression models in survival analysis based on the risk score. Lifetime Data Anal. 2, 315–328 (1996).

Grambsch, P. M., Therneau, T. M. & Fleming, T. R. Diagnostic plots to reveal functional form for covariates in multiplicative intensity models. Biometrics 51, 1469–1482 (1995).

Pepe, M. S., Janes, H., Longton, G., Leisenring, W. & Newcomb, P. Limitations of the odds ratio in gauging the performance of a diagnostic, prognostic, or screening marker. Am. J. Epidemiol. 159, 882–890 (2004).

Wu, H. C. et al. Derivation of androgen-independent human LNCaP prostatic cancer cell sublines: role of bone stromal cells. Int. J. Cancer 57, 406–412 (1994).

Source: Ecology - nature.com