Loss of NRF2 binding by Neoaves KEAP1

We constructed an alignment of KEAP1 coding sequences obtained from publicly available genomes (“Methods”; Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Data 1). Our final KEAP1 phylogenetic dataset spanned Drosophila, teleost fishes, and a detailed sampling of tetrapods (Fig. 1a–c; Supplementary Table 1). The encoded KEAP1 protein sequence is highly conserved between Amphibians, Mammals, and Reptiles and displays strong purifying selection across a wide sampling of mammalian orders (M8 PAML; Supplementary Table 2). KEAP1 is also highly conserved at the base of the Avian phylogeny within the Palaeognathae (Apteryx rowi) and the Galloanserae (Gallus gallus, Meleagris gallopavo, Anas platyrhynchos) (Fig. 1c).

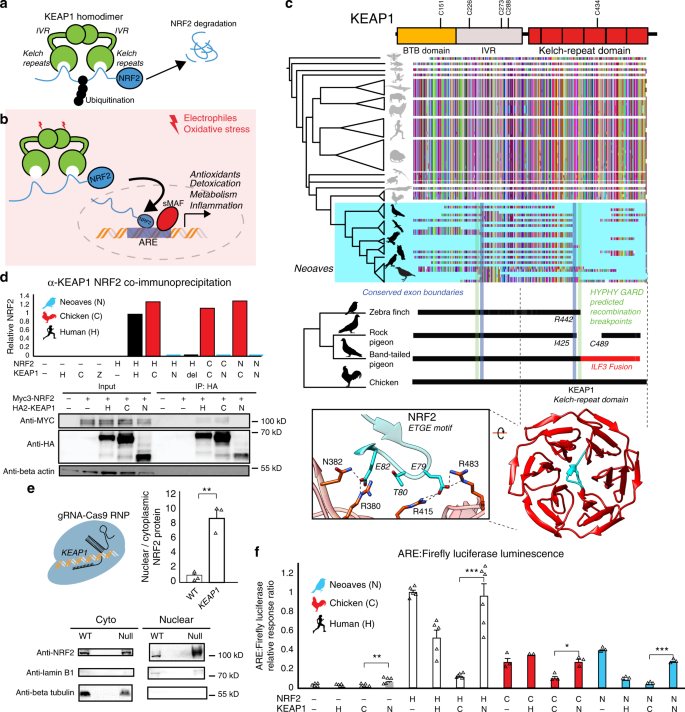

a KEAP1-mediated ubiquitination of NRF2 leads to proteasomal degradation30. b Under oxidative stress, covalent modification of KEAP1 cysteine sensors trigger NRF2 release and expression of antioxidant response element (ARE)-regulated genes. c Alignment of translated KEAP1 coding sequences obtained from animal genomes. Only fragments of KEAP1 could be retrieved across Neoaves genomes (Supplementary Data File 1). A C-terminal fragmentation pattern includes fusion with neighboring genes (ILF3) and coincides with statistically predicted genetic recombination breakpoints (HYPHY, GARD; green lines; “Methods”) that overlap KEAP1 exon boundaries (blue lines). This C-terminal fragmentation pattern affects the sequence integrity of the KEAP1 kelch-repeat domain, which is responsible for binding NRF2 (blue, zoom-in; [PDB ID: 2FLU])81. d Co-immunoprecipitation of HA-KEAP1 and MYC-NRF2 constructs from transfected HEK293T cell lysates. Relative NRF2/KEAP1 protein levels normalized to that of Human WT demonstrate that both Δ442-488 KEAP1 (del) and Neoaves (N) (Taeniopygia guttata) KEAP1 are incapable of binding co-transfected Human (H), Chicken (C), and Neoaves (N; Zonotrichia albicollis) NRF2. e KEAP1 loss of function (“null”) in Cas9-RNP-treated HEK293T cells leads to increased nuclear NRF2 localization. [N = 3; one-sided t test, p = 0.0013]. f Loss of NRF2 binding in Neoaves KEAP1 causes increased transcriptional activity of NRF2, as measured by ARE-driven luciferase expression in Cas9-RNP-treated HEK293T cells transfected with various Human and avian KEAP1 and/or NRF2 constructs [N = 6, except for: =2 (C/H); =3 (C/−; C/C; C/N, N/−, N/H, N/C, N/N); =5 (H/−, H/H, H/C); all N are biologically independent cells; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Two-sided t test]. Source data are provided as a Source data file. All data are presented as mean values. All error bars represent standard error.

In stark contrast to over 300 million years of KEAP1 sequence conservation, we could recover only fragments of KEAP1 coding sequences across 45 Neoaves genomes, altogether representing the work of 15 independent groups employing various sequencing technologies and genome assembly methods (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Data 1; “Methods”). We observed that the fragmentation pattern of Neoaves KEAP1 coding sequences closely corresponded to conserved KEAP1 exon boundaries in the Chicken (G. gallus), Pigeon (Columba livia), and Peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) genome assemblies (Supplementary Data 1; Fig. 1c). Using a genetic algorithm heuristic (GARD HYPHY; “Methods”), we found statistically significant phylogenetic evidence for recombination breakpoints in Neoaves KEAP1 nearly identical to these conserved exon boundaries (Fig. 1c, green lines; Supplementary Table 3), suggesting an ancestral recombination event in Neoaves KEAP1. Consistent with this, within a long-range annotated genome assembly for the band-tailed pigeon (Patagioenas fasciata), we found a KEAP1 coding sequence fused at the 3′ end to the adjacent ILF3 reading frame (accession OPJ82275.1), conjoined precisely at the conserved KEAP1 exon boundary and predicted recombination breakpoints we detected (R442, Human KEAP1 numbering; Fig. 1c); the noncontiguous remainder of the KEAP1 3′ end was inverted to the antisense strand. This suggested that the fragmentation pattern we observed in Neoaves KEAP1 was due to intrachromosomal rearrangements. To investigate this further, we extracted liver genomic DNA (gDNA) and complementary DNA (cDNA) from the passerine Zonotrichia albicollis (White-throated sparrow) and cloned KEAP1 coding sequences from multiple individuals (n = 3; “Methods”). Sanger sequencing identified KEAP1 coding sequences lacking the 220 amino acid segment encompassed by the predicted recombination breakpoints, which resulted in a frame-shift at the 3′ end (Supplementary Table 4).

These results provide evidence that the fragmentation pattern we observed (Fig. 1c) represents the loss of a fully contiguous KEAP1 coding sequence through intrachromosomal rearrangement. We hypothesized that this may have been accompanied by a loss of functional constraint on the KEAP1 coding sequence upstream of the R442 breakpoint. Consistent with this, in the recent golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) chromosome-level genome assembly we found a premature stop codon and frame-shift mutations immediately upstream of the recombination boundary (V377 Human KEAP1 numbering). Within the passerines, we found long branch lengths in the KEAP1 gene tree and significantly decreased selective constraint relative to the rest of the Avian clade (CmD PAML; “Methods”; Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 5). We also found a striking loss of functional residues in Passerine KEAP1 directly involved in mammalian KEAP1 sensing of ROS (C288; ref. 30) and cytosolic localization (I304; ref. 33), along with the loss of serine residues neighboring S104, which is involved in dimer formation and NRF2 degradation34. These residues are otherwise conserved across all vertebrate KEAP1 homologs28. Altogether these results suggest that a loss of functional constraint accompanied the loss of a fully contiguous KEAP1 during Neoaves evolution.

We hypothesized that the breakpoint near R442 would disrupt the NRF2-binding domain of Neoaves KEAP1 (Fig. 1c). Within the KEAP1 homodimer, this Kelch-repeat domain is responsible for binding NRF2 at the ETGE and DLG motifs, resulting in the consequent ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of NRF2 under normal physiological conditions (Fig. 1a; ref. 30). Canonically, NRF2 escapes degradation and becomes transcriptionally active only when electrophiles and/or ROS chemically induce conformational changes in KEAP1 via covalent modification of cysteine residues, which leads to NRF2 stabilization and consequent NRF2-mediated activation of a battery of cellular transcription programs (Fig. 1b; ref. 30). The loss of this important functional domain in Neoaves KEAP1 therefore suggests that NRF2 is constitutively active within Neoaves. To test this, we used a functioning Human KEAP1 coding sequence capable of binding NRF2 as a template to construct a mutant construct. This mutant Human KEAP1 contained a deletion (Δ442–488) within the NRF2-binding domain of KEAP1 (“Methods”), serving as a conservative representation of the Neoaves fragmentation pattern that starts at the exon boundary/recombination breakpoint near R442 (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Data 1). We also synthesized a predicted Neoaves KEAP1 coding sequence from the Zebra finch genome (Taeniopygia guttata; Supplementary Table Data 1), which served as a representative of the wide variety of Neoaves KEAP1 sequences that lack nearly 200 C-terminal amino acids relative to Chicken KEAP1 starting at R442 (Fig. 1c). Lastly, we directly cloned Chicken KEAP1 from cDNA we synthesized from lung tissue RNA (“Methods”).

We transfected HEK293T cells with constructs containing: Human WT KEAP1; Human Δ442-488 KEAP1 (del); Neoaves KEAP1 (N), or chicken KEAP1 (C) coding sequences (“Methods”). To compare NRF2-binding between these constructs, we co-transfected Myc-tagged NRF2 (“Methods”). We immunoprecipitated HA-tagged KEAP1 from transfected HEK293T cells under conditions favorable to NRF2-KEAP1 binding (“Methods”). In cells co-transfected with either Human or Chicken KEAP1, we observed co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) of Myc-tagged Human NRF2 (Fig. 1d), as well as both chicken and Neoaves (Z. albicollis) NRF2 constructs we cloned from cDNA synthesized from liver tissue RNA (“Methods”; Fig. 1d; Supplementary Fig. 2). By contrast, we found evidence for a complete loss of NRF2 binding by Human Δ442-488 KEAP1, as well as by Neoaves KEAP1, for any co-transfected Human, Chicken, or Neoaves MYC-tagged NRF2 (Fig. 1d; Supplementary Fig. 2). Altogether these bioinformatic and experimental assays indicate that NRF2 binding has been lost in Neoaves KEAP1.

Loss of KEAP1 binding increases NRF2 activity

We reasoned that a loss of NRF2 binding by Neoaves KEAP1 would result in increased NRF2 transcriptional activity (Fig. 1b). To test this, we conducted NRF2-driven luciferase assays in HEK293T cells. In order to reduce the background effect of endogenous Human KEAP1, we disrupted KEAP1 function in HEK293T cells through CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing (“Methods”; Supplementary Fig. 3). Consistent with a KEAP1 loss of function, we found significantly increased nuclear to cytosolic NRF2 ratios in Cas9-RNP-treated HEK293T cells (Fig. 1e). Furthermore, NRF2 transcriptional activity, target gene expression, and cellular resistance to oxidative stress were also significantly increased (Supplementary Fig. 4; “Methods”). This included a significant increase in NQO1 expression—an important NRF2-regulated detoxification enzyme32 that is pro-tumorigenic via stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-135. Incredibly, the CRISPR-Cas9-induced NQO1 overexpression corresponds directly with our observation of a completely deleted NQO1 locus within Neoaves (Supplementary Fig. 4).

We proceeded to co-transfect these cells with constructs containing Human, Chicken, or Neoaves KEAP1 (as described in the preceding section) along with a firefly luciferase construct under the control of an ARE regulatory element (“Methods”). This allowed us to quantify NRF2 transcriptional activity in response to co-transfected constructs containing KEAP1 coding sequences from different species. We found low levels of luciferase activity in cells co-transfected with either Human or Chicken KEAP1, but in contrast, luciferase expression was significantly increased in cells co-transfected with Neoaves KEAP1 (Fig. 1f), suggesting that the loss of the NRF2-binding domain in Neoaves KEAP1 (Fig. 1c) leads to an increase in NRF2 transcriptional activity. To investigate this further, we co-transfected constructs containing NRF2 coding sequences cloned from Human, Chicken, and Neoaves. We found that NRF2 from all species were transcriptionally active, driving luciferase expression (Fig. 1f). Consistent with our co-IP results (Fig. 1d), Human KEAP1 repressed the transcriptional activity of NRF2 homologs, an effect that was even stronger with Chicken KEAP1 (Fig. 1f). By contrast, we found significantly increased luciferase expression in all cells transfected with Neoaves KEAP1, regardless of the species origin of the co-transfected NRF2 (Fig. 1f). This provides direct evidence that increased Neoaves NRF2 transcriptional activity results from the loss of binding by Neoaves KEAP1.

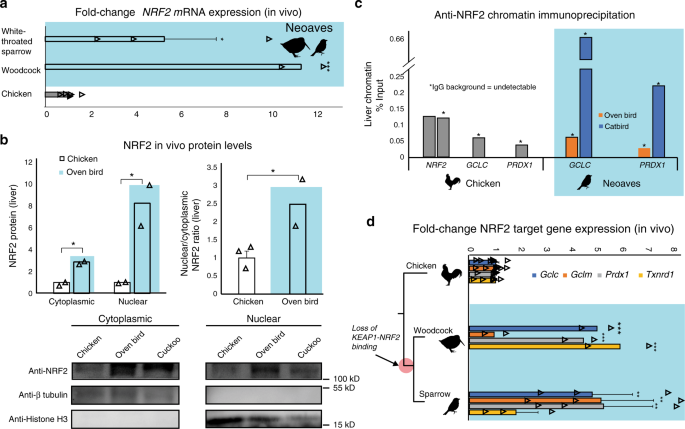

NRF2 is functional in vivo within wild Neoaves

With the loss of this critical KEAP1 repressor mechanism in the Neoaves clade, we next investigated NRF2 expression and activity in wild bird tissue (“Methods”; Supplementary Table 6). In order to study NRF2 mRNA expression, we synthesized cDNA from liver tissue (“Methods”). Through quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis, we identified NRF2 transcripts in two highly diverged Neoaves species (White-throated sparrow [n = 3] Z. albicollis; American woodcock [n = 2] Scolopax minor) each of which displayed significant NRF2 overexpression relative to that of Chicken (Fig. 2a). We next quantified protein levels of NRF2 in vivo. We extracted cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions from Chicken liver tissue, as well as that from two highly diverged Neoaves species (Oven bird Seiurus aurocapilla; Black-billed cuckoo Coccyzus erythropthalmus) (“Methods”). Consistent with a non-functional KEAP1 incapable of promoting NRF2 degradation, we found a significant increase in both cytosolic and nuclear NRF2 protein levels in Neoaves relative to that of Chicken (Fig. 2b). In addition, the nuclear to cytosolic ratio of NRF2 was significantly increased in Neoaves relative to Chicken (Fig. 2b). Since this ratio controls for NRF2 expression levels, it provides strong evidence that the increase in nuclear NRF2 in Neoaves relative to Chicken is due to a dysregulation by Neoaves KEAP1. We next investigated whether NRF2 is directly bound in vivo to the AREs upstream of two important NRF2 target genes, GCLC and PRDX1, which are involved in glutathione- and thioredoxin-based antioxidant systems, respectively32. We identified AREs upstream of GCLC and PRDX1 loci within the Chicken and Zebra finch (Neoaves) genomes (Supplementary Table 7; “Methods”) and detected NRF2 occupancy of these regulatory elements in Neoaves (Oven bird S. aurocapilla; Gray catbird Dumetella carolinensis) and Chicken using anti-NRF2 chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP; Fig. 2c; Supplementary Fig. 5). Furthermore, we identified two AREs upstream of the Chicken NRF2 locus (Supplementary Table 7) and demonstrated NRF2 occupancy of both of these regulatory elements using ChIP (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, we could not detect any AREs upstream of multiple Neoaves NRF2 loci (Supplementary Table 7), suggesting a loss of NRF2 autoregulation in Neoaves. To test for Neoaves NRF2 transcriptional activity, we investigated the expression of GCLC and PRDX1 mRNAs, along with other important NRF2 target genes (GCLM, TXNRD1). Consistent with the binding of NRF2 to GCLC and PRDX1 AREs (Fig. 2c), we identified mRNA expression of all four NRF2 targets across two highly diverged wild Neoaves species (White-throated sparrow [n = 3] Z. albicollis; American woodcock [n = 2] S. minor), which were significantly overexpressed relative to that of Chicken (Fig. 2d). Altogether these results demonstrate that NRF2 is expressed and functional in vivo within wild Neoaves and strongly suggest a loss of KEAP1 regulation of the NRF2 antioxidant response.

a Relative to Chicken (Gallus gallus; [N = 6 biologically independent animals]), liver NRF2 mRNA expression is significantly upregulated in wild Neoaves species (White-throated sparrow Zonotrichia albicollis [N = 3 biologically independent animals; p = 0.014]; American woodcock Scolopax minor [N = 2 biologically independent animals; p = 4.67 × 10−7]; one-sided t test). All data are presented as mean values. b NRF2 protein levels are elevated in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of wild Neoaves liver lysates (Oven bird Seiurus aurocapilla [N = 2 biologically independent animals]; Black-billed cuckoo Coccyzus erythropthalmus [N = 1 biologically independent animal]) relative to Chicken (Gallus gallus; [N = 2 biologically independent animals]). p = 0.0078 and 0.036 for cytoplasmic and nuclear, respectively. One-sided t test. Consistent with dysregulation of NRF2 by KEAP1, Neoaves (Oven bird Seiurus aurocapilla; [N = 2 biologically independent animals]) display increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios, relative to Chicken [N = 3 biologically independent animals]. p = 0.038, one-sided t test. c Liver chromatin immunoprecipitation using an anti-NRF2 antibody reveals that Chicken and Neoaves (Oven bird Seiurus aurocapilla; Gray catbird Dumetella carolinensis) NRF2 is bound to antioxidant-response elements (ARE) of GCLC and PRDX1 in vivo. NRF2 AREs could not be detected in Neoaves genomes, yet two AREs are bound by NRF2 in Chicken liver (note that IgG background is undetectable for all AREs, except for one of the two NRF2 AREs identified in Chicken, where it comprises only 0.6% of signal obtained with the NRF2 antibody; Source data). d NRF2 target genes (GCLC, GCLM, PRDX1, TXNRD1) are expressed in wild Neoaves (White-throated sparrow Zonotrichia albicollis [N = 3 biologically independent animals]; American woodcock Scolopax minor [N = 2 biologically independent animals]) and are significantly upregulated relative to Chicken [N = 8 biologically independent animals]. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. One-sided t test. Source data are provided as a Source data file. All error bars represent standard error.

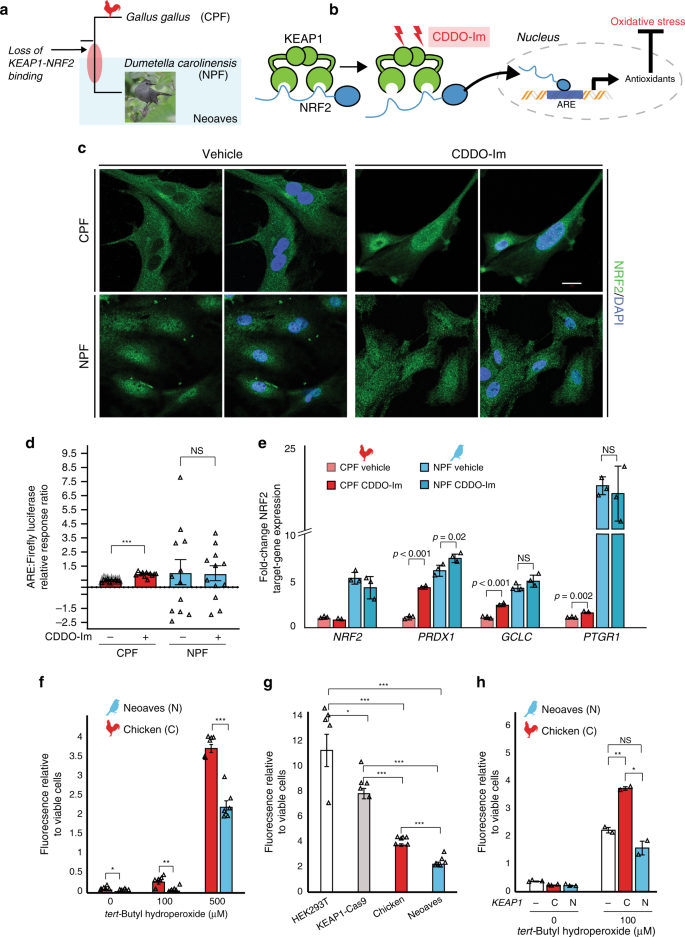

Constitutive NRF2 nuclear localization in Neoaves cells

Given the in vivo evidence for a loss of KEAP1 regulation of NRF2 in Neoaves, we conducted a series of experiments to investigate this finding under controlled in vitro conditions. We hypothesized that, if Neoaves have indeed lost KEAP1-mediated regulation of NRF2, then relative to Human and Chicken cells, NRF2 in Neoaves cells should display: (1) robust, constitutive nuclear localization and (2) a loss of inducibility by KEAP1 modulators. We used immunocytochemistry to analyze NRF2 immunofluorescence in Chicken primary fibroblasts (CPF) as well as in primary fibroblasts we isolated from a wild Neoaves individual (D. carolinensis; NPF; Fig. 3a). We exposed both cell types to a synthetic triterpenoid (CDDO-Im; 2-Cyano-3,12-dioxooleana1,9-dien-28-imidazolide) that induces NRF2 nuclear translocation through structural modification of KEAP1 thiol groups (Fig. 3b; “Methods”). Consistent with a functional and inducible NRF2-KEAP1 system, we found that Chicken NRF2 was strongly localized in the cytosol of CPF cells (Fig. 3c, vehicle) and also displayed a strongly inducible nuclear localization response to CDDO-Im treatment (Fig. 3c). In striking contrast, Neoaves cells displayed strong constitutive NRF2 nuclear localization (Fig. 3c, vehicle), and there was no increase in NRF2 nuclear localization in Neoaves cells treated with CDDO-Im (Fig. 3c, CDDO-Im, bottom row). These results are consistent with the loss of KEAP1-mediated regulation of NRF2 in Neoaves.

a Chicken (CPF) and Neoaves (Dumetella carolinensis) primary fibroblasts (NPF) were used to evaluate KEAP1 regulation of NRF2 in vitro. “Gray Catbird” [CC BY 2.0] Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren. https://flickr.com/photos/80270393@N06/17166164877. No changes were made. b CDDO-Im is a chemical modulator of KEAP1 that induces release of NRF2 and consequent gene transcription at nuclear antioxidant response elements (AREs; “Methods”). c Immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy (scale bar (white) for all micrographs is 20 µm) of cells exposed to vehicle (DMSO) or 50 nM of CDDO-Im. NRF2 immunofluorescence in CPF and NPF cells. This experiment was repeated independently N = 5 times, with similar results. d Luciferase assays of vehicle- and CDDO-Im-treated CPF cells [N = 10 biologically independent cells; ***p = 5.07 × 10−12, one-sided t test] and NPF cells [N = 12 biologically independent cells]. e Multiple NRF2 target genes are significantly upregulated in Chicken cells upon CDDO-Im treatment [N = 2 biologically independent cells] relative to vehicle [N = 3 biologically independent cells]. These same target genes are constitutively expressed at high levels in Neoaves cells and show no response to CDDO-Im [N = 3]. p Values are noted above each comparison. One-sided t test. f Significantly decreased oxidative stress in NPF cells relative to CPF cells when challenged with various concentrations of tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBh) [N = 6 biologically independent cells, except for at 500 µM tBh where N = 5 biologically independent cells]. 0 μM, *p = 0.045; 100 μM, **p = 0.002; 500 μM, ***p = 1.54 × 10−5. Two-sided t test. g Human cells (HEK293T) with Cas9-induced KEAP1 loss of function display significantly decreased oxidative stress relative to wild type when challenged with 500 μM tBh [N = 5 biologically independent cells]. Two-sided t test. *(p < 0.05); **(p < 0.01); ***(p < 0.001). This oxidative stress reduction is strikingly similar to that between NPF and CPF cells. h Oxidative stress is increased in NPF cells transfected with Chicken KEAP1 (C) relative to those transfected with Neoaves KEAP1 (N; Taeniopygia guttata) or mock transfected (−) and exposed to various concentrations of tBh [100 μM, N = 2 biologically independent cells; 0 μM, N = 3 biologically independent cells]. Mock vs. C, **p = 0.006; Mock vs. N, p = 0.14; C vs. N, *p = 0.014; two-sided t test. Fluorescence Ex/Em: 492–495/517–527 nm. Source data are provided as a Source data file. All data are presented as mean values. All error bars represent standard error.

To evaluate and quantify the impact of loss of NRF2 regulation by KEAP1 in Neoaves cells, we measured NRF2 transcriptional activity using two approaches: a firefly luciferase construct under the control of an ARE, and by measuring the endogenous expression levels of NRF2 target genes (“Methods”). We found a significant increase in both NRF2-driven luciferase activity and target gene expression in CPF cells treated with CDDO-Im (Fig. 3d, e), providing additional evidence that G. gallus has maintained the inducible KEAP1-NRF2 system conserved among other vertebrates28,30. This is also consistent with our luciferase experiments in HEK293T cells that demonstrated recombinant Chicken KEAP1 strongly suppresses NRF2 transcriptional activity (Fig. 1f). In contrast, NPF cells treated with CDDO-Im displayed no change in luciferase activity and only small changes in NRF2 target gene expression following CDDO-Im treatment (Fig. 3d, e), consistent with our immunocytochemistry data (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, NRF2 target genes were constitutively expressed at high levels in NPF cells even in the absence of CDDO-Im (Fig. 3e). Since Neoaves NRF2 is indeed capable of driving luciferase expression in HEK293T cells (Fig. 1f) and is expressed and functional in wild-type Neoaves tissues (Fig. 2b–d), our immunocytochemistry, luciferase and gene expression experiments therefore provide strong evidence that an inducible KEAP1-NRF2 system has been lost in Neoaves. This has resulted in constitutive NRF2 nuclear localization and target gene expression.

We hypothesized that the loss of KEAP1 regulation of NRF2 would have strong consequences for cellular resistance to oxidative stress burden. Consistent with this, we found significantly decreased oxidative stress in Neoaves vs. Chicken cells challenged with various concentrations of tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBh; Fig. 3f). To investigate whether this was due to a loss of KEAP1, we employed two complementary experimental strategies. First, we compared the effects of KEAP1 loss of function on oxidative stress using KEAP1-Cas9-treated HEK293T cells. As expected, oxidative stress was significantly decreased in KEAP1 loss of function cells relative to wild type, and interestingly, this relative decrease was strikingly similar to that between Chicken vs. Neoaves cells (Fig. 3g). This suggests that a KEAP1 loss of function mediates this difference in resistance to oxidative stress burden. Second, we attempted to rescue KEAP1 repression of NRF2 in Neoaves cells through transfection with Chicken vs. Neoaves KEAP1 constructs. We found that Chicken KEAP1 significantly increased oxidative stress in Neoaves cells, relative to a mock transfected control (Fig. 3h), suggesting repression of endogenous Neoaves NRF2. This is consistent with binding of Chicken KEAP1 to Neoaves NRF2 (Fig. 1d; Supplementary Fig. 2), which represses Neoaves NRF2 transcriptional activity (Fig. 1f). By contrast, transfection of exogenous Neoaves KEAP1 had no effect on oxidative stress in Neoaves cells exposed to 100 μM tBh (Fig. 3h), consistent with the loss of NRF2 binding and repression by Neoaves KEAP1 (Fig. 1d, f). Taken together, these results demonstrate that KEAP1 loss of function in Neoaves has resulted in an increased resistance to oxidative stress.

Evolutionary trade-offs of constitutive NRF2 activity

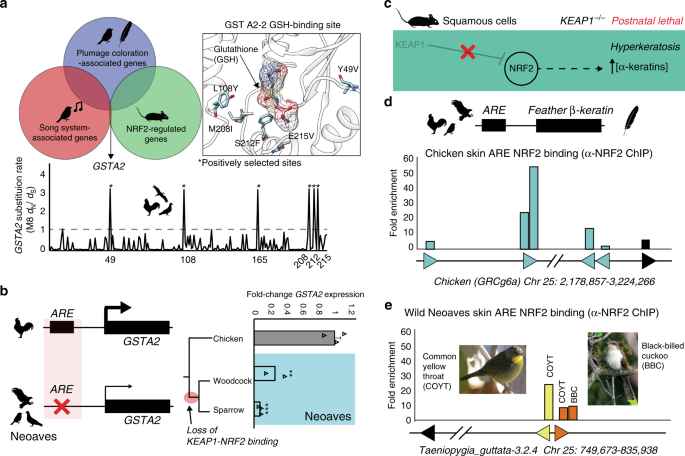

Our experiments with Cas9 genome editing, along with wild Neoaves tissues and primary cells, provide strong evidence that the loss of KEAP1-NRF2 binding in wild Neoaves reduces the cellular oxidative stress burden through constitutive NRF2 activity. Given the breadth of NRF2-regulated genes32, we hypothesized that constitutive NRF2 activity may have also shaped the evolution of important Neoaves-specific physiological traits. We conducted a literature review into potential overlaps between gene sets known to be associated with: (1) NRF2-regulation in mice; (2) plumage coloration in Neoaves; and (3) the Zebra finch song system32,36,37. We found that glutathione S-transferase A2 (GSTA2) is shared among all three gene sets—an enzyme catalyzing the conjugation of reduced glutathione to hydrophobic electrophiles32. Given the association of this NRF2 target gene with important Neoaves-specific phenotypic traits, we hypothesized that natural selection may have altered the functional constraints of Neoaves GSTA2, potentially as compensation for the constitutive activation of Neoaves NRF2. We investigated evidence of positive selection on GSTA2 codons by constructing a large phylogenetic dataset of Avian GSTA2 coding sequences (Supplementary Table 8), followed by dN/dS statistical analyses. We found highly significant evidence of positive selection acting on Avian GSTA2 (p < 10−17; M8 PAML, Supplementary Table 9) and identified with high statistical confidence (posterior probabilities >0.99) several GSTA2 sites targeted by this acceleration in evolutionary rates (dN/dS = 3.50; Fig. 4a). Incredibly, all GSTA2 sites under positive selection display Neoaves-specific amino acid variants and are located near the glutathione-binding site within a homology model of the Zebra finch GSTA2 amino acid sequence (Fig. 4a; “Methods”). This is consistent with potential functional adaptation of GSTA2 enzymatic activity, which in turn suggests that the constitutive activation of NRF2 in Neoaves has altered the functional constraints of Neoaves GSTA2.

a Glutathione S-transferase A2 (GSTA2) is shared among gene sets associated with: (1) NRF2-regulation in mice; (2) plumage coloration in Neoaves; and (3) the Zebra finch song system32, 36, 37. Avian GSTA2 is a target of positive selection (p < 10−17; M8 PAML, Supplementary Table 9). GSTA2 sites targeted by natural selection (dN/dS = 3.50) are located within the glutathione (GSH)-binding site (PDB ID: 2WJU) and display Neoaves-specific amino acid variants. b Loss of an NRF2 antioxidant response regulatory element (ARE) in Neoaves (Woodcock, N = 2 biologically independent animals; Sparrow, N = 3 biologically independent animals; Supplementary Table 8) is consistent with a significant decrease in GSTA2 expression relative to that of Chicken [N = 3 biologically independent animals]. **p = 0.005, ***p = 0.0012, respectively, one-sided t test. Data are presented as mean values. c KEAP1 knockout mice die from starvation shortly after birth from hyperkeratosis of the gastrointestinal tract, likely through overexpression of α-keratins and loricrins in squamous cells38. d AREs were detected upstream of β-keratins across avian genomes (Supplementary Table 7). Skin chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with anti-NRF2 antibody revealed NRF2 occupancy of AREs for feather β-keratins (grey) and loricrin (black) identified within the Chicken genome. e AREs for feather β-keratins are markedly deceased in the Zebra finch genome (Supplementary Table 7) and display a trend toward decreased NRF2 occupancy in ChIP analysis of the skin obtained from two highly diverged wild Neoaves species (common yellow throat Geothlypis trichas and Black-billed cuckoo Coccyzus erythropthalmus). “Female Common Yellowthroat” (CC BY-SA 4.0) Sandhillcrane https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Female_Common_Yellowthroat.jpg, no changes were made. “Black-Billed Cuckoo” (C) 2008 Wolfgang Wander (GFDL). Source data are provided as a Source data file. All error bars represent standard error.

To further investigate this, we searched for AREs upstream of the GSTA2 locus in several avian genomes representing a broad sampling of the avian phylogeny (Supplementary Table 8; “Methods”). In contrast to other NRF2 target genes containing an NRF2-bound ARE (GCLC, PRDX1; Fig. 2c; Supplementary Table 7), we could only detect an ARE upstream of Chicken GSTA2; we could not find any evidence of an ARE upstream of GSTA2 across multiple Neoaves species (Fig. 4b; Supplementary Tables 7, 8). Next, we conducted qPCR analysis of GSTA2 transcripts from liver cDNA synthesized from wild Neoaves liver tissues (“Methods”). We found a highly significant decrease in Neoaves GSTA2 transcripts in comparison to that of Chicken across a phylogenetically diverse Neoaves species (Fig. 4b), suggesting that the loss of the GSTA2 ARE in Neoaves has resulted in the downregulation of GSTA2. Relative to that of other NRF2 target genes, which contained AREs and were upregulated in Neoaves relative to Chicken (GCLC, PRDX1), the evolution of GSTA2 gene expression therefore appears to have been differentially affected by the constitutive activation of NRF2 in Neoaves. Natural selection therefore appears to have modulated both the GSTA2 protein sequence as well as GSTA2 expression in Neoaves. Given the unique association between GSTA2 and Neoaves-specific phenotypic traits, we hypothesize that these evolutionary signatures represent compensation for the potentially deleterious effects of constitutive NRF2 activation.

The physiological risks of constitutive NRF2 activation due to loss of KEAP1 binding have been demonstrated in vivo through KEAP1 knockout mice, which die from starvation shortly after birth from hyperkeratosis of the gastrointestinal tract, likely through overexpression of α-keratins and loricrins in squamous cells (ref. 38; Fig. 4c). In addition to α-keratins, avian skin keratinocytes also express β-keratin genes, which combine with α-keratins to form avian skin appendages (feathers, scales, claws, beaks; ref. 3). We reasoned that if α-keratins are regulated by NRF2 in mouse squamous cells, then it may be the case that β-keratins are regulated by NRF2 in avian skin. We focused on feather β-keratins since they are considered to be expressed at the highest levels compared to other skin appendages3. We searched the Chicken genome for ARE regulatory elements upstream of feather β-keratin loci on chromosome 25 (“Methods”; Supplementary Table 7). With loricrin serving as a positive control for our ARE consensus query sequence, we identified multiple feather β-keratins with predicted AREs in this region of the Chicken genome, some of which had multiple AREs per locus (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Table 7). Using chromatin purified from Chicken skin, we detected NRF2 occupancy of these ARE regulatory elements using anti-NRF2 ChIP (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Fig. 5). This suggests that NRF2 may regulate the expression of feather β-keratins within avian skin. We next hypothesized that, similar to the loss of NRF2-mediated ARE-regulation in Neoaves GSTA2 (Fig. 4b), selection pressures may also be acting to suppress NRF2 regulation of Neoaves β-keratins, potentially as compensation for the constitutively active NRF2 in Neoaves (Fig. 3c). Consistent with this, we detected a marked decrease in ARE elements upstream of β-keratin loci on Zebra finch chromosome 25 (Fig. 4e; Supplementary Table 7), as well as a decrease in NRF2 occupancy at these β-keratin AREs in the skin chromatin of two wild Neoaves diverged across ~80 million of years of evolution (Common yellow throat Geothlypis trichas and Black-billed cuckoo C. erythropthalmus; Fig. 4e; Supplementary Fig. 5). This strongly suggests that the NRF2-mediated regulation of β-keratins we detected in Chicken skin has been compensated for by the loss of AREs and downregulation of ARE binding by NRF2 at Neoaves β-keratin loci. This pattern closely mirrors the loss of NRF2-mediated ARE-regulation in Neoaves GSTA2 (Fig. 4b). Together these analyses provide in vivo evidence that the evolution of NRF2-associated feather development genes may have been shaped by the constitutive activation of NRF2 in Neoaves.

Loss of KEAP1 is associated with increased metabolic rates

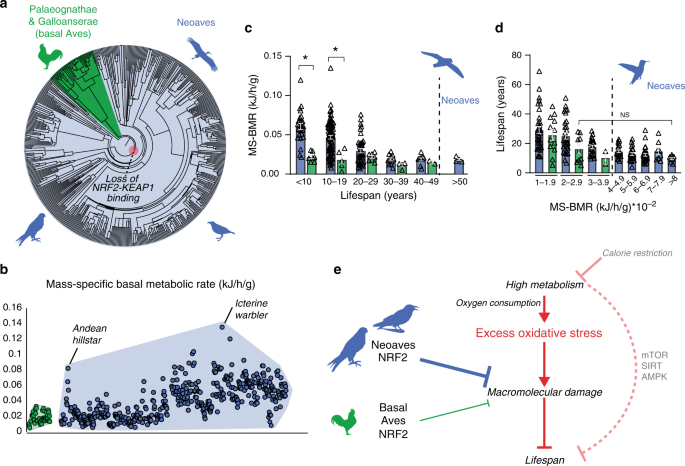

We demonstrated that the loss of NRF2 repression by KEAP1 in Neoaves has resulted in increased cellular resistance to oxidative stress burden, which may potentially form an adaptive mechanism capable of counterbalancing high levels of ROS in Neoavian tissues. Since high oxygen consumption and metabolism can produce excess ROS that damage macromolecules, this imposes a key limitation on lifespan10,12,21,22,23,24. We therefore reasoned that, by altering redox homeostasis, an enhanced NRF2 antioxidant defense may have impacted the evolution of Neoavian metabolism and lifespan. We hypothesized that the loss of KEAP1 would therefore be associated with increases in metabolic rates and lifespan. To investigate this, we obtained publicly available body mass and basal metabolic rate (BMR) data for >530 avian species as well as maximum lifespan data for >1000 avian species (“Methods”). Consistent with our hypothesis, we observed that, across the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5a), mass-specific BMRs (MS-BMRs) reach higher ranges in Neoaves species relative to that of basal Aves (e.g., ostrich, kiwi, fowl; Fig. 5b).

a Phylogenetic relationships of avian taxa for which mass-specific basal metabolic rates (MS-BMR) are available (“Methods”). Red highlight denotes the Neoavian ancestor where KEAP1 binding of NRF2 was lost. b MS-BMR reach higher ranges in Neoaves (blue) species relative to basal Aves (green). Avian orders are grouped by phylogenetic relationships along the X-axis (“Methods”). c MS-BMR differs significantly between Neoaves and basal Aves species with equivalent lifespans (<10 years, p = 0.03; 10–19 years, p = 0.02; PI Kruskal–Wallis; Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Tables 10 and 11). Neoaves with low MS-BMR reach higher lifespans than any basal Aves (>50 years). Neoaves: n = 180 biologically independent animals; basal Aves: n = 25 biologically independent animals. Data are presented as mean values. d Neoaves with MS-BMR values higher than that of any basal Aves still maintain statistically indistinguishable lifespans, despite a nearly fourfold increase in MS-BMR (Kruskal–Wallis; Supplementary Table 10). Neoaves: n = 175 biologically independent animals; basal Aves: n = 23 biologically independent animals. Data are presented as mean values. e High metabolism impacts lifespan through nutrient-sensing pathways (mTOR, SIRT, AMPK) as well by generating excess oxidative stress, aggravating age-associated cellular and molecular damage (see “Discussion” for references). An enhanced NRF2 antioxidant response via the loss of KEAP1 would likely lower the risk of macromolecular oxidative damage expected to result from high avian metabolism and oxygen consumption. By altering redox homeostasis to tolerate higher levels of excess oxidative stress, the loss of KEAP1 may have enabled these increases to Neoaves lifespan and metabolic rates. Source data are provided as a Source data file. All error bars represent standard error. * = phylogenetic statistical significance.

To quantify these differences, we first controlled for lifespan by stratifying Neoaves and basal Aves species into lifespan groups (Fig. 5c), where within each group the mean lifespans of basal Aves and Neoaves were statistically indistinguishable (Mann–Whitney; Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Table 11). We then conducted a non-parametric statistical analysis on MS-BMR data for species falling into KEAP1 functional (basal Aves) vs. non-functional categories (Neoaves) (Supplementary Table 10). To evaluate statistical significance, we corrected for the effects of phylogeny39 by constructing a time-calibrated avian phylogeny for the >200 avian species for which both MS-BMR and lifespan data were available (Supplementary Fig. 9A, “Methods”). We simulated continuous character evolution across the phylogeny to generate empirical null distributions of Kruskal–Wallis (KW) H values, which we used to evaluate the statistical significance of KW tests, comprising phylogenetically independent (PI) KW test (“Methods”). Using the presence of a functional KEAP1 as the categorical factor in our model, we found a significant increase in MS-BMR between Neoaves and basal Aves within two different lifespan groupings (<10 years, p = 0.03; 10–19.9 years, p = 0.02; Supplementary Table 10), providing phylogenetic evidence that the loss of KEAP1 is associated with increased metabolic rates in Neoaves. Furthermore, despite displaying nearly identical MS-BMR values to that of the basal Aves, multiple Neoaves species can reach maximum lifespans beyond the range of any basal Aves in this dataset (Fig. 5c; >50 years). To further investigate this, we stratified all species into MS-BMR-based groups, where the mean MS-BMR of basal Aves and Neoaves were statistically indistinguishable within each group (Mann–Whitney; Supplementary Fig. 9; Supplementary Table 11). Across all MS-BMR groups, there is a clear trend of higher lifespan ranges in Neoaves compared to that of basal Aves (Fig. 5d). Furthermore, even when comparing basal Aves to Neoaves species with nearly fourfold increased metabolic rates (2–2.9 vs. >8 MS-BMR, respectively), there are no significant decreases to Neoaves lifespan (Fig. 5d). This suggests that the constraints imposed on lifespan by MS-BMR (Fig. 5e) have been relaxed in Neoaves, potentially explaining why significant increases to MS-BMR have had no discernable trade-off effect on lifespan during the Neoavian radiation (Fig. 5c, d). Since our analysis presents statistical evidence that the loss of KEAP1 was associated with significant increases to metabolic rates, this raises the intriguing hypothesis that constitutive NRF2 activity may have facilitated the simultaneous diversification of Neoavian MS-BMR and lifespan. As we discuss below, it will be of critical importance to directly investigate this hypothesis using future experimental models.

Source: Ecology - nature.com