Study species

Burying beetles use small vertebrate carcasses to reproduce and as a food source for themselves and their offspring53,54,55. Previous research in the lab has shown that Nicrophorus beetles can reproduce at least three times over the course of their lifetimes56. Laboratory breeding experiments have also shown that when burying beetles reach a carcass, they mate, take ~3–4 days to remove the fur or skin, and smear the carcass with the liquid secreted by the mouth and rectum to delay decomposition57. Next, they make the carcass into a “meatball”, bury it under the soil, and eventually lay eggs near the carcass58. Our observations indicate that the larvae, which have a total of three-instar stages, hatch ~1 day after egg laying, at which time they begin to take up the nutrients of the meatball (H.-Y.T., Y.-M.F., T.-N.Y., B.-F.C., and S.-F.S., unpublished data). Two weeks after burial, the larvae grow into three-instar larvae that are ready to leave the nest for pupation. In total, the larvae take 1.5 months to emerge as adults (H.-Y.T., Y.-M.F., T.-N.Y., B.-F.C., and S.-F. S., unpublished data). The average age of the beetles in our experiments was 135 days after the larvae leave the meatball for pupation, and there was no age difference between the sexes (H.-Y.T., Y.-M.F., T.-N.Y., B.-F.C., and S.-F.S. unpublished data).

Study site

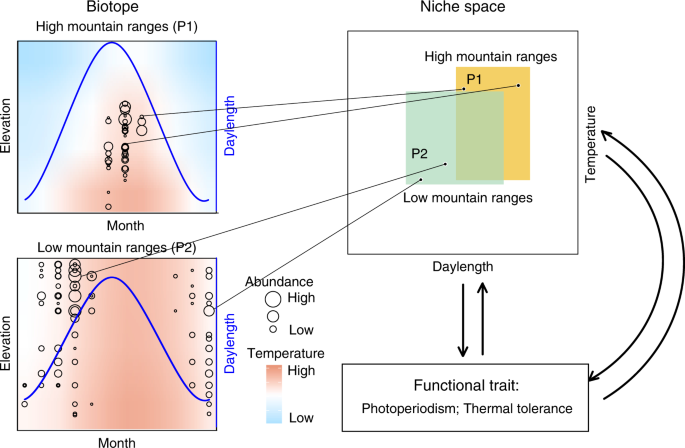

The burying beetle Nicrophorus nepalensis (Coleoptera: Silphidae) occurs widely across mountain ranges throughout Asia59. We quantified the monthly population densities of N. nepalensis at 100 m intervals along elevational gradients at five mountain ranges in Asia located from 24 °N to 30 °N that varied in maximum elevation from 700 m to 4100 m (Fig. 2). We define the breeding season of N. nepalensis as the months that at least one beetle appeared in the trap. The mountain ranges, which differed in both their thermal environment (due to elevation) and daylength (due to latitude), included two low mountain ranges—Wulai in Taiwan, with natural habitats ranging from 200 m (121° 51′ E, 24° 83′ N) to 900 m (121° 54′ E, 24° 85′ N) above sea level and Amami Oshima in Japan, ranging from 60 m (129° 27′ E, 28° 32′ N) to 700 m (129° 32′ E, 28° 30′ N)—and three high mountain ranges—Mt. Lala in Taiwan, ranging from 400 m (121° 51′ E, 24° 60′ N) to 2000 m (121° 43′ E, 24° 73′ N), Mt. Hehuan in Taiwan, ranging from 500 m (121° 00′ E, 23° 98′ N) to 3200 m (121° 27′ E, 24° 13′ N), and Mt. Jiajin in China, ranging from 800 m (102° 84′ E, 30° 23′ N) to 4100 m (102° 68′ E, 30° 86′ N).

Density survey

To estimate beetle densities and determine breeding phenology at each site, we averaged the number of beetles by month because we replicated the experiments for ~3 years. Adult burying beetles were collected using hanging pitfall traps baited with rotting pork32,60 (mean ± SE: 100 ± 10 g) at Mt. Hehaun, Taiwan (January 2016 to May 2018), Mt. Lala, Taiwan (February–April, August, and November 2017; February, June, and July 2018), Wulai, Taiwan (January 2016 to May 2018), Amami Oshima, Japan (February 2015; April 2016; March–April 2018), and Mt. Jiajin, China (June–August 2017, January, June–August 2018, and November 2019; Fig. 1). The pitfall traps were always checked in the morning on the fourth day of the experiment. The air temperature at every site was measured using iButton® devices that were placed ~120 cm above the ground within a T-shaped PVC pipe to prevent direct exposure to the sun. Since carcass preparation and burial, which occur above ground, are critical to the successful breeding of burying beetles, we believe that air temperature is an appropriate measure of environmental temperature (see also refs. 32,60,61). Although we acknowledge that soil temperature could be important for the larva development, those data are not available.

We only brought two male and two female beetles from each plot back to the lab to ensure that we did not have a strong influence on the population density in the field. All wild-caught beetles were transported to the laboratory walk-in growth chambers and allowed to reproduce in captivity. Beetles captured in the short photoperiod season were kept in short-day conditions (10 h light: 14 h dark), and those captured in the long photoperiod season were kept in long-day conditions (14 h light: 10 h dark). The temperature and humidity in all of the walk-in growth chambers were set to the same conditions in both photoperiodic regimes (daily temperature cycles between 19 °C at noon and 13 °C at midnight; RH: 83–100%), which imitated natural conditions at 2100 m elevation on Mt. Hehaun. Beetles were housed individually in 320 ml transparent plastic cups and fed superworms (Zophobas morio) weekly if they were kept for more than three days before the experiment.

To conduct the experiments, we obtained permits required by local governments, forestry bureaus and national parks annually in Taiwan in 2014–2018, MOUs between two academic institutes required by the National Forestry and Grassland Administration in China, and the experimental permit required by the Ministry of Environment in Japan.

To bring the beetles collected abroad back to Taiwan, we obtained the permit required by the Bureau of Animal and Plant Health Inspection and Quarantine in 2018 and 2019.

Establishment of lab strains

We established lab strains from each population by pairing male and female beetles collected from each mountain range for the subsequent experiments. The generation of the initial lab strain was denoted as wild-type (WT). In the WT generation, we established at least 20 families, ~600 individuals in total, to maintain population structure in the lab. We used beetles collected in different hanging pitfall traps to ensure that founding beetles in the lab strains were unrelated to each other. We bred a pair of beetles in a 20 × 13 × 13 cm box with 10 cm of soil and a rat carcass (75 ± 7.5 g). The parents were allowed to remain in the breeding box until larvae dispersed to pupate (~2 weeks after introducing adult beetles). All dispersing larvae from each breeding box were collected and allocated to a small, individual pupation box. The larvae were evenly but arbitrarily divided and raised under two photoperiodic conditions, as described above.

Temperature data

We used average monthly climate data to depict the temperature pattern at five mountain ranges based on WorldClim v2 (30 s spatial resolution; records from 1970 to 2000 (ref. 31)): http://worldclim.org/version2.

Common garden experiment

Common garden experiments allow for a test of local adaptation vs. phenotypic plasticity. To observe how beetle reproductive behavior from each population changes in response to photoperiod, we conducted a solitary pairing experiment in two photoperiodic regimes: long- (10 h dark: 14 h light) and short-day conditions (14 h dark: 10 h light). The temperature and humidity were set to the same conditions in both photoperiodic regimes, as described above. All larvae from a pair of beetles were separated into the two photoperiodic conditions immediately at the time of dispersal. We used sexually mature beetles aged 2–3 weeks after emergence.

To observe how beetle reproductive behavior from each population changes in response to temperature, we conducted pair breeding experiments in three average temperature condition: 12 °C, 16 °C, and 20 °C. The humidity was set to the same conditions in all temperature conditions (RH: 83–100%). The photoperiod regime was set to the same as short-day conditions (14 h dark: 10 h light) for the Wulai, Amami Oshima, Mt. Lala, and Mt. Hehuan population, but to long-day conditions (10 h dark: 14 h light) for the Mt. Jiajin population since these beetles can only breed under long-day conditions. All larvae from a pair of beetles were separated into the two photoperiodic conditions immediately at the time of dispersal. We used sexually mature beetles aged 2–3 weeks after emergence.

We placed a male and a female pair with a rat carcass (75 ± 7.5 g) under both photoperiodic conditions in a transparent plastic container (21 × 13 × 13 cm with 10 cm of soil depth) and gave them 2 weeks to breed. If they did not bury the carcass by the 14th day after the experiment began, the pairs were moved to a new container with a new carcass under the same environmental conditions to repeat the experiment. A case in which the parents fully buried the carcass and had offspring within two trials was regarded as successful breeding attempt. A case in which the parents failed to bury a carcass, or they buried it but did not have offspring in two consecutive trials, was regarded as a failed breeding attempt. Each experiment was conducted with different pairs that thus are independent samples.

Transplant experiment

Reciprocal transplant experiments allow for direct tests of local adaptation, whereby the fitness of the native population is compared to that of the non-native one. To this end, we conducted reciprocal transplant experiments between the low mountain range Wulai and high mountain Mt. Hehuan populations in January, February, December, and June, early August in 2016 and 2017 to compare winter and summer conditions. In each season, we chose the three sites on each mountain that the highest beetle abundance according to our field surveys. We conducted transplant breeding experiments in which lab strains from either population were transplanted to either non-native mountain range (i.e., the lab strain individuals originating from the Wulai population were transplanted to Mt. Hehuan, and vice versa) or to the native mountain range as a control (i.e., the lab strain individuals originating from the Wulai or Mt. Hehuan population were transplanted to Wulai or Mt. Hehuan, respectively).

In each trial, we placed a WT male and a WT female with a rat carcass (75 ± 7.5 g) in the breeding pot, which was covered by a gauze web and buried in the soil to keep the beetles inside the pot and prevent other insects from invading. Each breeding pot is 19 cm in length, which is deep enough for beetles to bury the carcass and lay eggs. A 75 g rat carcass was placed on the soil and covered with a 21 × 21 × 21 cm iron cage with a mesh size of 2 × 2 cm to prevent vertebrate scavengers from accessing the carcass32,60. We quantify both breeding likelihood and breeding success. Breeding likelihood, defined by the burial rate, is quantified by whether burying beetles bury the carcass (i.e., burial or non-burial). To quantify breeding success, we exhumed the carcasses ~14 days after they were buried and collected third instar larvae, if there were any. If the parents had offspring, we regarded it as a successful breeding event; if not, we regarded it as a failed breeding event. Each experiment was conducted with different pairs that thus are independent samples.

Ovary dissection

To understand whether beetle preparation for breeding is based on photoperiodic control, we dissected and quantified ovarian weight at three-time points: on days 0, 7, and 14 after emergence. The general dissection protocol followed the method described by Wilson and Knollenberg62. Briefly, we placed the beetles on ice for 1 h to euthanize them. We then measured their body weight and cut down their abdomens. Ovaries were dissected into Ringer’s solution. Next, we removed the spermatheca and accessory glands and immediately quantified the wet weights of each organ.

Thermal tolerance

To investigate burying beetles’ thermal tolerances—CTmax and CTmin—we tested each populations’ thermal tolerance range, following the protocol of Sheldon and Tewksbury63. Briefly, we measured each burying beetle’s pronotum, and then transferred them to separate glass cups (200 mL, with lid) at an initial temperature of 25 °C for 1 h to ensure beetle body temperatures were the same going into experimental tests. A 5 mm layer of peat soil was placed on the bottom of each cup to allow beetles to walk freely. Each cup containing a beetle was then submerged into either a 50 °C or −10 °C water bath to test its upper or lower thermal limit. We chose 50 °C as the warm trial temperature because it made beetles achieve the upper thermal limit efficiently before desiccation. We chose −10 °C as the cold trial temperature because we found that this temperature did not immediately lead to the loss of righting for the beetles (but colder temperatures did). Since a layer of peat soil was placed at the bottom of the cup, the actual soil temperatures that a beetle experienced in the cup were ~42 °C and 0 °C for the CTmax and CTmin experiments, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2). A layer of Vaseline was also applied to the wall of the glass cup to prevent beetles from escaping. During the whole process, we used a thermal camera (Inc., SC305, FLIR® Systems) with the software ThermaCAM Researcher Professional 2.10 to capture the pronotum area of each individual as their core temperature of CTmax or CTmin. The thermal tolerance of beetles was determined when an individual reached its critical temperature, lost coordinated leg movements, and could no longer remain in a righting position64. After the experiments, we returned the beetles to the walk-in growth chambers.

Climate change simulations

We used the scenario of RCPs 8.5 for 2081–2100 (ref. 33) to obtain the increasing mean surface air temperature relative to the base period and directly added to the temperature pattern (data from WorldClim31) along the five mountain ranges. We then compared the possible distribution in fixed and varying phenological conditions by overlapping their recent thermal niche ranges in a way that projected climate change.

Data analysis

We used non-parametric regression—LOESS65 with the smoothing span of 0.5—to test for differences in abundance across the five populations and five mountain ranges along the elevational and temperature gradients. To validate the reciprocal projection method of Hutchinson’s duality framework, we used a bootstrap method66—a random sampling technique that can help determine the sample size effect on the sampling errors—to compare the thermal niche breadth based on complete and partial data from Wulai and Mt. Hehuan. Briefly, we randomly sampled data for 1000 times for from different numbers of months. We found that randomly sampling data from the 3 months that at least one beetle appeared can generate reasonably accurate thermal niche predictions (Supplementary Fig. 1), although sampling 6 months or more generated the most accurate predictions. Thus, although we do not have year-round beetle occurrence data for the populations of Amami Oshima and Mt. Jiajin, the population density data in these populations—which we sampled four and 3 months, respectively—is enough to generate accurate temporal niche predictions.

We calculated the thermal niche breadth for different numbers of months to determine the effect of sample size on the confidence intervals of the data. We used a GLM to analyze factors influencing the breeding likelihood (i.e., burial rate) and ovarian weights of the beetles. The parents’ physical characteristics (age, pronotum width, and mass) were treated as covariates for the burying behavior experiments and the outcome (1 = burial, 0 = non-burial) was fitted as a binomial response term to test the difference in the probabilities of the breeding likelihood between photoperiods. Ovarian weight was fitted as a Gaussian response to identify the beetle’s development stage (stage 1 = just emerged, stage 2 = emerged after 7 days, and stage 3 = emerged after 14 days). A GLM was used to compare thermal niche breadth among the five populations. GLMMs were used for the fitness assays in the transplant experiments. To test for differences in the probability of breeding successfully between the two mountain ranges along the elevational and temperature gradients, the outcome of breeding (1 = success, 0 = failure) was fitted as a binomial response term. Environmental factors (elevation, daily minimum air temperature) were fitted as covariates of interest and we used the experimental location ID as a random factor. Post hoc pairwise comparisons (Tukey tests) were carried out using R package lsmeans67. All statistical analyses were performed in the R 3.0.2 statistical software package68.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Source: Ecology - nature.com