Despite the moral, economic and health imperative to provide everyone with safe drinking water every day, Africa has struggled to achieve or sustain global water policy goals.1,2,3,4 As we enter the third wave of global development goals (2015–2030) following the International Decade of Drinking Water and Sanitation (1980–1990) and the Millennium Development Goals (MDG, 2000–2015), it is expedient to reflect why billions of dollars of effort still leave over half the rural population of sub-Saharan Africa without basic drinking water, making the region by far the most underserved globally.1 Meeting the global MDG target for improved water access can largely be attributed to progress in China and India.5 Translating global water policy into meaningful change in rural Africa requires a closer examination of the water choices of the rural poor in three related domains, which can be achieved by (1) considering drinking water as a composite good with different attributes across service levels and management arrangements, (2) understanding behavioural responses to alternative management models; and (3) exploring the payment preferences of rural people to determine the extent to which cost-sharing is socially-acceptable.

Drinking water attributes encompassing the quality, quantity, reliability, proximity and affordability of the service are now acknowledged as both a global development goal and a human right.6 However, there is limited social choice mapping of these attributes. For example, the global goal is to achieve to safely-managed drinking water on-demand, on-site and free of contamination for everyone by 2030. An estimated 2.1 billion people lack this service level including almost everyone in rural Africa. The second order, global goal is to achieve basic water access which is an ‘improved service’ with a return collection time of 30 min or less. Given the history of progress in rural Africa, achievement of even basic water services for everyone by 2030 would be an unprecedented policy success. Indeed, the off-site supply of improved water from handpumps and other infrastructure poses a collective action challenge in managing a point source used by multiple people for multiple purposes at different times of the year.7,8

The institutional arrangement that emerged in the 1980s, and has endured in rural Africa, is community-based management.9,10 It is a policy in which government and donors have funded the installation of infrastructure with the community responsible for funding ongoing operation and maintenance. The assumption is that communities wish to manage their water supplies and are capable of doing so effectively and equitably. These assumptions have been questioned widely.11,12,13,14,15 But what is the alternative? Urban water supplies in Africa have largely been managed by the public sector, sometimes with good performance, if regulated independently and monitored closely, but the majority are heavily subsidised and perform poorly.16 Performance-based models have recently emerged in rural water management with early evidence that they may be an alternative service provider in a more plural institutional arrangement between the state, market and community.17,18,19,20 These initiatives reflect renewed international development attention to support capacity to plan, finance and implement local solutions where government, private sector and communities can forge a commitment to greater self-reliance to deliver basic services for everyone.21 We explore this changing policy landscape from the perspective of rural water users.

Policy design and water user choices

What is unclear is the behavioural responses of rural people to alternative water supply attributes and institutional arrangements. Social choice theory suggests there will be competing preferences between attribute levels across water quality, reliability, affordability and proximity. Which matters most will likely vary by current water delivery performance, alternative water supplies, education, wealth, gender and the institutional arrangement.22,23 Do women prefer water quality more than reliability? Do water users have a preference between public, private or community management? Current policy is agnostic on such points providing a notionally ‘improved water source’ and assuming it will be managed with affordable tariffs and reliable performance. Increasing evidence disputes these assumptions but provides limited evidence as to whether investing more in a reliable service will elicit higher and more regular payments. Data from Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda and Zimbabwe indicate when a rural waterpoint fails it takes between 13 and 214 days to repair, with a modal value of around one month.11,15,24,25,26,27 A related measure of failure is downtime by functionality on the day of a visit. A study of 453,177 rural waterpoints in 38 African countries estimates an average of one in four waterpoints is not working at any one time.28 Given such long repair times carry high economic, social and health costs, particularly for women and girls,29 we focus our experiment on improvements in repair times to see how this affects payment behaviours.

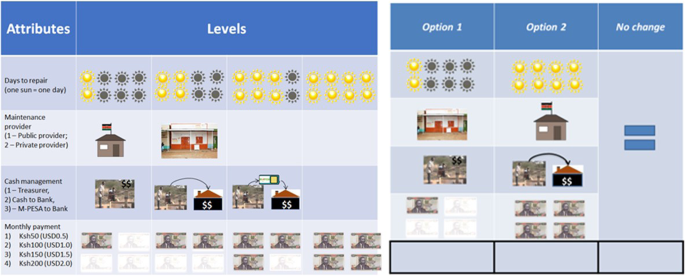

Multi-country evidence across Africa indicates systemic late or non-payment for community waterpoints in rural areas.14,17,18,30 Which attributes of community water supply would elicit higher and better payment behaviours? Methodologically, there is a challenge in administering hypothetical, trade-off experiments orally to people with limited or no education or familiarity with such techniques. Here, we develop a pictorial format with careful explanation and test cards to allow water users to make their choices across competing alternatives or accept the current situation (status quo). Without improved understanding of what may incentivise user payments, public investments in infrastructure may provide limited financial returns and transient social impacts, which may partly explain the unsatisfactory progress achieved in rural water security in rural Africa to date.

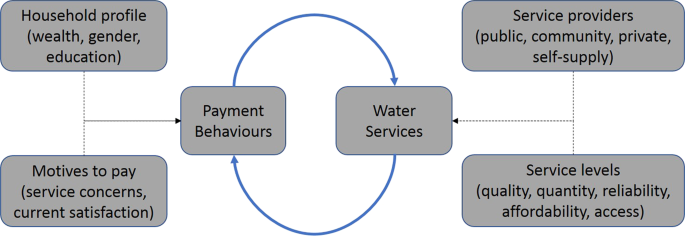

A conceptual model summarises the discussion above and anticipates the choice modelling specification that follows (Fig. 1). We propose interactions between the payment behaviours of water users and the water services. This explicitly recognises the normative features of drinking water service levels for Sustainable Development Goal 6.1, and contextualises them by ‘who’ provides the service and ‘why’ people choose to pay, or not. Payment behaviours are shaped by the profile of users and their motives. Salient profile characteristics include the wealth, education attainment, and water demand of the household, as well as, the sex of the respondent. Water is considered a ‘normal good’ where higher wealth is likely to be associated with higher demand. Demand is related to both domestic (drinking, bathing, washing and laundry) and productive uses, particularly livestock watering from community water supplies in rural Africa.7,31 The sex of the respondent is of importance given the gendered roles and inequalities of water collection. For example, women in sub-Saharan Africa are six times more likely than men to have the burden of water collection duties.29 Motives to pay for improved drinking water explore user concerns across dimensions of cost, quality, accessibility, quantity, reliability, satisfaction with current service levels, and seasonal demand to recognise the influence of rainfall variation on demand.32 Water services are determined by the service provider and the level of service delivery. The latter are not homogenous but vary qualitatively and quantitatively by the quality, quantity, reliability, affordability and distance. Service provision policy has largely transferred responsibilities to communities, the response to which we explore through investigating user preferences to alternative models by local government or private sector.

Conceptual model of payment behaviours and drinking water services. Blue curved arrows: denote interactions between payment behaviours of water users and water services. Black straight arrows: denote factors shaping payment behaviours, and demand factors determining water services

Tracing policy and practice from the 1980s

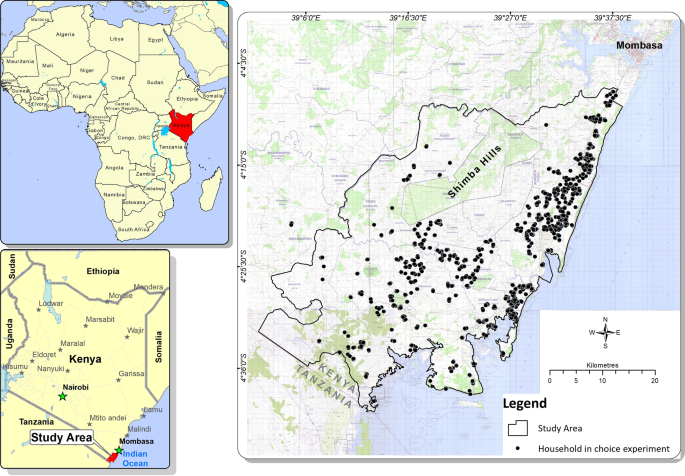

The study site is Kwale county on the south coast of Kenya (Fig. 2). The location provides a unique historical context in the emergence and adoption of community-based management of handpumps in the 1980s, which has informed rural water policy across Africa and Asia until the present day. Further, the handpumps upon which most communities depend were installed in this period and were linked to training and support in village-level operation and management. The findings of the time indicate community adoption of this behavioural model to operate, finance and maintain handpumps used by community members. Thirty years on it is instructive to review the extent to which, and reasons why, water user choices still hold firm or have shifted to alternative or hybrid approaches. By examining the choice preferences of these communities we elicit insights into how and why behavioural norms may have shifted from their training and adoption of community operational, financial and management practices. Rural and remote, the county has high levels of poverty and a dependency on handpumps for domestic and productive water uses.27 While a bi-modal rainfall pattern provides an average of 1400 mm per year, extended dry spells lead to observed and sustained spikes in handpump usage as alternative water supplies become unavailable.32 A sample of 531 handpump locations was used as a sampling frame for a household survey administered in late 2013 and early 2014.30 At each of the 531 functional and non-functional handpumps, a stratified random sample of households provided 3500 households of which a random draw of 1560 households participated in the choice experiment.

Location of choice respondents in Kwale county, Kenya. Source: J. Katuva. The map illustrates locations of Kenya (upper left), the study site (lower left) and the households (right)

The experimental design identifies four-choice attributes with varying levels (Fig. 3): (1) maintenance service provider (public, private), (2) guaranteed days for repairs (2, 4, 6, 8), (3) cash management (treasurer/cash, bank account, mobile money), (4) monthly household payment (USD 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0). The status quo option reflects community maintenance and the local payment arrangements, which are commonly cash. An orthogonal, main effects design generated 10 choice cards, each with two alternatives and a status quo option eliciting 10 choice responses. Attribute design emerged from examination of the literature including a study of over 25,000 handpumps in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Uganda concluding that “greater efforts are needed to test and evaluate alternative models for managing handpump water supplies”.13 The modelling strategy has two stages. First, a conditional logit model (CLM) estimates the main attributes followed by interactions across four hypotheses of behavioural change: (a) multidimensional wealth, (b) education, (c) sex of respondent, and (d) household concerns. Second, a latent class model (LCM) specified by a discrete distribution of preferences to estimate heterogeneity following the assumption the variance in the error term is not constant but depends on individual observations.33,34,35,36

Pictorial design of choice attribute levels (left panel) and test choice card (right panel). The left panel presents the attributes and levels of the choice experiment, while the right panel illustrates three options for the pilot choice card, including two alternatives (option 1, option 2) and ‘no change’, which reflects the existing community management

Source: Resources - nature.com