Rural water service provision typically prioritises quantity over quality, which is often assumed to be adequate where groundwater is used. This practice maintains the separation of water safety from other aspects of rural water service provision, thereby establishing a false dichotomy—one that is reinforced by contradictory assumptions about whether water quality matters to the public. These assumptions obscure issues of community access to resources and knowledge. The empowerment dilemma expressed by LWMs in terms of intent to manage versus ability to pay, action knowledge14, and self-efficacy15,16 is reflected in the literature on the sustainability of (a) community self-financing of recurrent operations and maintenance costs17,18 and (b) water safety behaviour at the household-level19,20,21. Researchers have called for further exploration into the roles of ability to pay and self-efficacy for determining sustainable service delivery18 and sustaining safe water behaviour22. Here we demonstrate the significance of these empowerment dimensions for water safety management at the community scale and emphasise that lack of empowerment does not equate to apathy.

Moving beyond the question of whether water quality matters, and to whom, the dilemma analysis also revealed that water quality monitoring is deterred by fears that it will threaten functionality. Thereby, further reinforcing the quantity versus quality dichotomy. Fears relate to a lack of contextualisation and a reactive mode of operating in which solutions to quality concerns involve supply disruption or closure. But fears are also related to disempowerment, and the self-preserving requirement to avoid attracting criticism by revealing problems that one cannot resolve. Responsibility is a key point of contention.

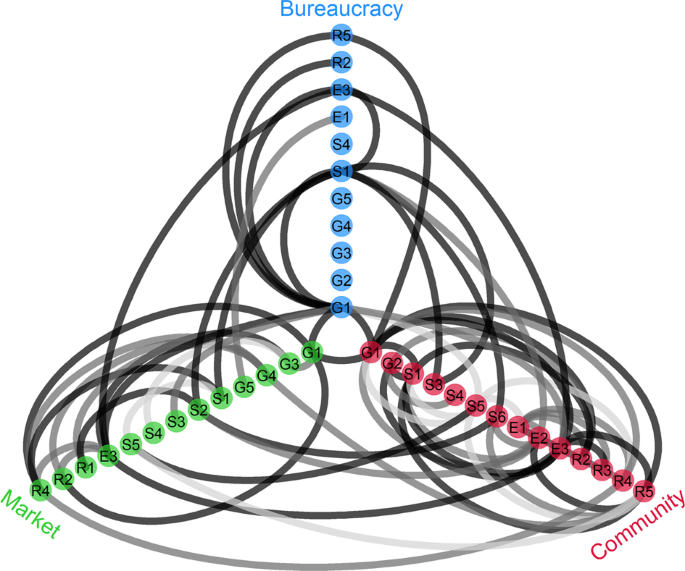

Indeed, perhaps the biggest deterrent of monitoring is that it draws attention to the question of who is responsible for using the results (this question is additionally complex because perceived responsibility varies with contaminant type). Introducing monitoring can reveal problems that nobody realised were there, leading multiple stakeholders in interviews to liken it to opening Pandora’s box. As a result, RWSPs that take on water quality monitoring encounter dilemmas about their organisational identity and purpose and may find themselves facing opposing demands from bureaucracy and community regarding how the results of monitoring are shared and used. This could be problematic given the importance of institutional cooperation for advancing service delivery in rural areas.

Yet, the assumptions, fears, and abnegation of responsibility that deter rural water quality monitoring may be mitigable. There is a need:

to contextualise monitoring results so that quantity and quality are jointly considered.

for external support to empower LWMs to engage with water safety and to enable bureaucratic divisions and service providers to act on responsibilities.

to approach the technical and institutional design of water supply systems such that quality is considered early—thus increasing ability to respond to problems.

These needs are consistent with an established risk-based approach: water safety planning23. As of 2017, 93 countries had implemented water safety planning at varying scales, and although uptake has been relatively low in Sub-Saharan Africa, at least 10 countries are engaged in efforts to scale-up the use of the approach in both urban and rural areas24. This includes Kenya, where the national water services regulator has published guidance promoting the approach25. In the following sections, we briefly discuss how the barriers identified by the dilemma analysis may be addressed through a water safety planning approach. In so doing, we also speak to the main challenges of implementing water safety planning in rural areas.

Contextualising monitoring results

The WHO have recommended water safety planning since 2004; they continue to do so23 and practical guidance is readily available26,27, including specific adaptations for small community supplies28,29,30,31,32. Rather than relying on a purely reactive management approach, which reinforces the quality versus quantity dichotomy, water safety planning seeks to identify and address risks holistically and pre-emptively. Within the water safety planning model, quality, quantity, proximity, reliability, and acceptability of supply are to be considered concurrently to minimise use of supplementary water from unimproved sources and unhygienic storage. When implemented as intended, such an approach should alleviate functionality fears by encouraging consideration of monitoring results in terms of overall health burden.

By design, water safety planning should improve contextualisation of water quality information and, therefore, has potential to mitigate some of the barriers that were highlighted by the dilemma analysis. But the key challenge here is implementing the approach as intended. Reactive management and associated ‘obstruction of water delivery’ has been described even for cases where water safety planning is actively being attempted33 (p. 5). As discussed in the following sections, implementing water safety planning as intended is likely to require external support and early inclusion.

External support is needed

The dilemma analysis found that lack of empowerment creates barriers to improving water safety through monitoring. This is also reflected in the literature on water safety planning, which frequently highlights inadequate financing34,35,36,37 and capacity34,35,38,39,40 as substantial barriers to successful implementation. In rural areas in particular, inadequate financing and capacity have meant that water safety planning efforts focus on the early stages of the approach (assembling a team, describing the water supply and identifying hazards, developing and implementing a plan for improvement) but neglect the latter stages of monitoring, verification, and iterative learning33,39, which are crucial to the effectiveness and sustainability of the approach29,37. Financial and capacity-building support is needed.

External support for rural water services is not new, a review of studies assessing external support provision since the 1970s describes support in many forms, provided by NGOs, governments, community associations, or businesses41. Half of the studies in the review focussed on SSA. Ironically, the most reported challenge for external support programmes was that providers themselves lacked sufficient resources to adequately support communities. The RWSP model is a hybrid in that it leverages resources from the private sector, donors, and government, as well as consumers. RWSPs, with their ability to capitalise on economies of scale and attract centralised funding and well-trained staff, are potentially positioned to channel and appropriately localise support for water safety planning.

Nevertheless, sharing results with LWMs and users in a way that builds understanding and is consistent with a holistic view of safety requires a full-programme educative approach to communication. The dilemma analysis highlighted that such an approach is important for enabling stakeholder cooperation around monitoring. Additionally, this comprehensive approach is consistent with official guidance and research studies that have recommended that rural water safety planning efforts include hazards occurring on consumers’ premises26,37,42, since addressing such hazards requires long-term effort towards sustained behaviour change. From the RWSP perspective, however, while the benefits are recognised, there are persistent doubts about scalability of a comprehensive approach. Further work investigating the financial and logistical feasibility of incorporating such an approach in the RWSP model would be useful.

Early adoption of water safety planning

With external support in place, monitoring and the latter stages of water safety planning become more feasible. The dilemma analysis found, however, that barriers to monitoring go beyond issues of finance and capacity. While external support should empower more action on water safety, there will always be trade-offs on how resources are used, and the convention of dichotomising quantity and quality will continue to hamper water safety efforts. The dichotomy sustains the view that taking responsibility for water safety is an excessive burden. As reflected in the literature, this view of monitoring—and water safety planning more broadly—as burdensome is a key difficulty for securing buy-in to the approach35,43,44. Though we have focussed in this study on rural context, the quantity versus quality dichotomy has broader relevance. For example, a study of water safety planning in urban utilities in India, Uganda, and Jamaica described a ‘deliver first, safety later’ mind-set among customers and implementers, which the researchers deemed a ‘significant limiting influence on [water safety plan] implementation’ (p. 902)45.

The water safety planning approach aims to supersede the vague notion of ‘everyone having a role to play’ in ensuring water safety, by requiring that specific, actionable responsibilities be allocated. But fragmented institutional structures make meaningful stakeholder engagement difficult46 and technical path dependencies limit viable response options. When a water safety planning approach is adopted early in the life of a water supply project, it can contribute to institutional design (including allocation of responsibilities) and technical design (maximising the choice of viable source selection, protection, and treatment response options). Thus, early water safety planning may clarify and operationalise responsibilities for water safety. In combination with sufficient external support, it may mitigate the barriers that otherwise arise from uncertain responsibilities and reticence towards raising awareness of quality concerns without an ability to respond to them. Early adoption is also beneficial when considered in light of ‘community readiness’44, because safety considerations are built into the design of a new system rather than being retrofitted to an existing system, when the acceptability of change and scope for community input are much reduced.

When quality issues are not adequately contextualised and strategies are not in place to address them, water quality monitoring can threaten cooperation between bureaucratic, market, and community institutional groups. In exploring the potential of RWSPs in SSA to contribute to the SDG 6.1 effort, we highlight the importance of building a technical and institutional structure around water quality monitoring so that it adds legitimacy to each institutional group rather than threatening them. Such a structure is consistent with the intentions of the water safety planning approach, which may be effective given external support and especially if adopted early. Those who fund rural water service provision should consider that a quantity first, quality later approach makes securing water safety additionally difficult because technical and institutional path dependencies limit response options and discourage stakeholder cooperation around monitoring. Instead, systems should be designed with preventative risk management in mind from the outset.

Source: Resources - nature.com