DeJesus-Hernandez, M. et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72, 245–256 (2011).

Majounie, E. et al. Frequency of the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 11, 323–330 (2012).

Mori, K. et al. The C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat is translated into aggregating dipeptide-repeat proteins in FTLD/ALS. Science 339, 1335–1338 (2013).

Ash, P. E. A. et al. Unconventional translation of C9ORF72 GGGGCC expansion generates insoluble polypeptides specific to c9FTD/ALS. Neuron 77, 639–646 (2013).

Donnelly, C. J. et al. RNA toxicity from the ALS/FTD C9ORF72 expansion is mitigated by antisense intervention. Neuron 80, 415–428 (2013).

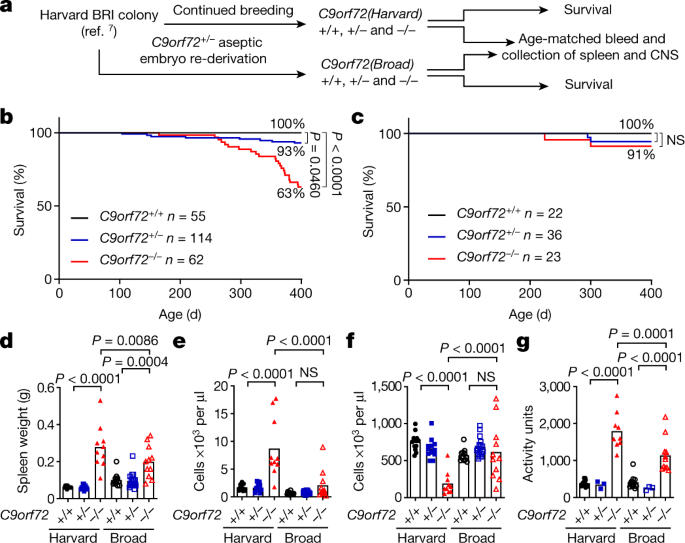

O’Rourke, J. G. et al. C9orf72 is required for proper macrophage and microglial function in mice. Science 351, 1324–1329 (2016).

Burberry, A. et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the C9ORF72 mouse ortholog cause fatal autoimmune disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 347ra93 (2016).

Nassif, M., Woehlbier, U. & Manque, P. A. The enigmatic role of C9ORF72 in autophagy. Front. Neurosci. 11, 442 (2017).

Shi, Y. et al. Haploinsufficiency leads to neurodegeneration in C9ORF72 ALS/FTD human induced motor neurons. Nat. Med. 24, 313–325 (2018).

Whary, M. T. & Fox, J. G. Natural and experimental Helicobacter infections. Comp. Med. 54, 128–158 (2004).

Flannigan, K. L. & Denning, T. L. Segmented filamentous bacteria-induced immune responses: a balancing act between host protection and autoimmunity. Immunology 154, 537–546 (2018).

Ugolino, J. et al. Loss of C9orf72 enhances autophagic activity via deregulated mTOR and TFEB signaling. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006443 (2016).

Jiang, J. et al. Gain of toxicity from ALS/FTD-linked repeat expansions in C9ORF72 is alleviated by antisense oligonucleotides targeting GGGGCC-containing RNAs. Neuron 90, 535–550 (2016).

Atanasio, A. et al. C9orf72 ablation causes immune dysregulation characterized by leukocyte expansion, autoantibody production, and glomerulonephropathy in mice. Sci. Rep. 6, 23204 (2016).

Miller, Z. A. et al. Increased prevalence of autoimmune disease within C9 and FTD/MND cohorts. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 3, e301 (2016).

Fredi, M. et al. C9orf72 intermediate alleles in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis. Neuromolecular Med. 21, 150–159 (2019).

Stine, J. G. & Lewis, J. H. Hepatotoxicity of antibiotics: a review and update for the clinician. Clin. Liver Dis. 17, 609–642, ix (2013).

Ransohoff, R. M. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science 353, 777–783 (2016).

McCauley, M. E. & Baloh, R. H. Inflammation in ALS/FTD pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. 137, 715–730 (2019).

Zhao, W., Beers, D. R. & Appel, S. H. Immune-mediated mechanisms in the pathoprogression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 8, 888–899 (2013).

Zondler, L. et al. Peripheral monocytes are functionally altered and invade the CNS in ALS patients. Acta Neuropathol. 132, 391–411 (2016).

Zhang, G. X., Li, J., Ventura, E. & Rostami, A. Parenchymal microglia of naïve adult C57BL/6J mice express high levels of B7.1, B7.2, and MHC class II. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 73, 35–45 (2002).

Lall, D. & Baloh, R. H. Microglia and C9orf72 in neuroinflammation and ALS and frontotemporal dementia. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 3250–3258 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. The C9orf72-interacting protein Smcr8 is a negative regulator of autoimmunity and lysosomal exocytosis. Genes Dev. 32, 929–943 (2018).

Li, H. et al. Different neurotropic pathogens elicit neurotoxic CCR9- or neurosupportive CXCR3-expressing microglia. J. Immunol. 177, 3644–3656 (2006).

Krasemann, S. et al. The TREM2–APOE pathway drives the transcriptional phenotype of dysfunctional microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunity 47, 566–581.e9 (2017).

Keren-Shaul, H. et al. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell 169, 1276–1290.e17 (2017).

Nilsson, H.-O. et al. High prevalence of Helicobacter species detected in laboratory mouse strains by multiplex PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and pyrosequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 3781–3788 (2004).

Blacher, E. et al. Potential roles of gut microbiome and metabolites in modulating ALS in mice. Nature 572, 474–480 (2019).

Zhai, R. et al. Strain-specific anti-inflammatory properties of two Akkermansia muciniphila strains on chronic colitis in mice. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 239 (2019).

Erny, D. et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 965–977 (2015).

Olson, C. A. et al. The gut microbiota mediates the anti-seizure effects of the ketogenic diet. Cell 173, 1728–1741.e13 (2018).

Harach, T. et al. Reduction of Abeta amyloid pathology in APPPS1 transgenic mice in the absence of gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 7, 41802 (2017).

Sampson, T. R. et al. Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell 167, 1469–1480.e12 (2016).

Tremlett, H., Bauer, K. C., Appel-Cresswell, S., Finlay, B. B. & Waubant, E. The gut microbiome in human neurological disease: a review. Ann. Neurol. 81, 369–382 (2017).

Fang, X. et al. Evaluation of the microbial diversity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using high-throughput sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1479 (2016).

Brenner, D. et al. The fecal microbiome of ALS patients. Neurobiol. Aging 61, 132–137 (2018).

DeSantis, T. Z. et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5069–5072 (2006).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010).

Henderson, K. S. et al. Efficacy of direct detection of pathogens in naturally infected mice by using a high-density PCR array. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 52, 763–772 (2013).

Source: Ecology - nature.com