Study area

The study was conducted upstream of the tidal area of the Gironde estuary (45°02′45.80″ N, 0°36′41.56″ W), where the Dordogne and Garonne rivers discharge (Southwestern France, Fig. 4). The Garonne-Dordogne hydrographic network hosts one of the largest populations of sea lamprey in Europe20,28. The Dordogne River runs over 475 km (mean flow = 216 m3/s) from its source in the Massif Central to its confluence with the Garonne River. The Garonne River is the largest river of Southwestern France and runs over 580 km (mean flow = 647 m3/s) from its source in the Pyrenees to the Atlantic Ocean. The predatory fish guild in both rivers was composed of one native species (the Northern pike Esox lucius), and three non-native species (the pikeperch Sander lucioperca, the pike Perca fluviatilis and the European catfish).

Sea lamprey tagging and tracking

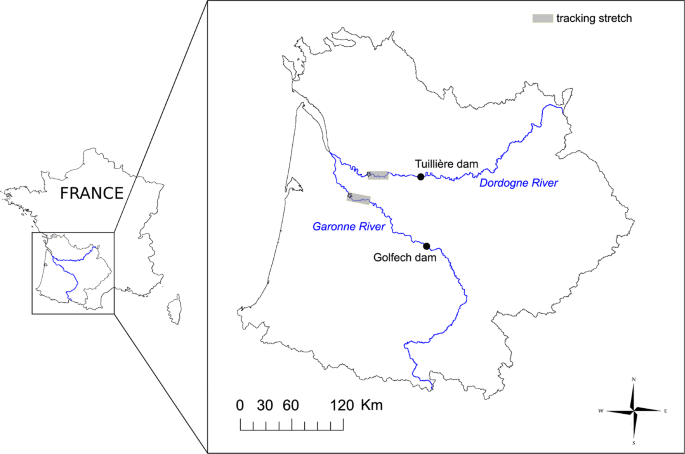

Sea lamprey tagging and tracking was conducted in two stretches of the Dordogne River (Dordogne) and the Garonne River (Garonne) to study lamprey survival during the migration period (from March to April 2019) (Fig. 6).

Location of the sea lamprey tracking stretches on Dordogne and Garonne rivers (grey boxes). Black stars indicate lamprey release points. Black circles indicate the localisation of the dams where the permanent video fish-counting stations are installed. The map was generated using QGIS 2.14.0-Essen (https://www.qgis.org/en/site/) and INKSCAPE 0.92.4 (https://inkscape.org).

Forty-nine sea lampreys were captured, tagged and released to the river: 39 individuals (mean ± SD total body length = 88 ± 4 cm) in Dordogne and 10 individuals (mean ± SD total body length = 82 ± 5 cm) in Garonne. We choose to test more individuals on Dordogne than on Garonne as the population is greatest in the former river. Lamprey capture, tagging and tracking was performed twice in Dordogne to mitigate the risk and potential consequences of failure: 25 tagged lampreys were released on March 11th (Dordogne 1) and 14 tagged lampreys were released on March 25th (Dordogne 2). The manipulation was performed once in the Garonne River on March 21th (Garonne).

Lampreys were captured by one professional fisherman using sea lamprey pots at Lamothe-Montravel (44°51′05.09″N, 0°01′36.50″E) and Barsac (44°36′30.98″N, 0°19′00.96″W) for Dordogne and Garonne, respectively (Fig. 6). Lampreys were then equipped with a 36-mm radio transmitter 1815C (Advanced Telemetry System Inc., NW Isanti, MN, USA), weighing 8 g in air, to follow lamprey movements (e.g. as in29,15). Each lamprey was also tagged with an acoustic Vemco tag model V5 (Vemco Ltd., Amirix Systems Inc., Bedford, Nova Scotia, Canada) operating at 180-kHz and with a 143 dB acoustic power output. This ‘predation tag’ is small (4.3 × 5.6 × 12.7 mm) and light (0.65 g in air). It is also equipped with a biopolymer that is digested when conditions are acidic, as it is the case inside predators’ gastrointestinal tracts. Biopolymer digestion leads to a change in the transmitter’s identification number from a pre-predation ID to a post-predation ID (see30 for more details).

For each tracking experiment, lampreys were anaesthetized using a benzocaine solution at 10% (0.7 ml/l), measured and tagged. Surgery consisted of a 2–3 cm incision to insert the tags. The incision was closed with 4–5 synthetic absorbable sutures (Vicryl, Ethicon). The procedure took less than 5 minutes. Lampreys were then transferred to a tank filled with river water for at least 15 minutes to recover from anesthesia. Then, they were released in the river inside a cage. The cage was equipped with a small aperture allowing lampreys to find the exit. All individuals rapidly found the exit (i.e. in less than 5 minutes) confirming their good condition and swimming performance.

Tagged lampreys were regularly monitored with receivers embarked on a boat during 25 to 50 days after release, depending on the tracking experiment. Radio-telemetric and acoustic monitoring consisted in traveling along both studied stretches to detect tagged sea lampreys. The Dordogne stretch was 32-km long and located between Castillon-la-Bataille (44°51′07.50″N, 0°02′34.80″W; 8 km downstream from the release place) and Le Fleix (44 °C52′32.12″N, 0°14′40.56″E). The Garonne stretch was 30-km long and located between Cadillac (44°38′20.91″N, 0°19′19.09″W; 3 km downstream from the lamprey release place) and La Réole (44 °C34′52.49″N, 0°02′28.15″W). Each time one lamprey was radio-tracked with the embarked radio receiver R4500C (Advanced Telemetry Systems Inc., NW Isanti, MN, USA), GPS coordinates were captured and acoustic signals were recorded with an embarked Vemco VR100 acoustic receiver (Vemco Ltd., Amirix Systems Inc., Bedford, Nova Scotia, Canada). Lamprey status was interpreted as alive or consumed depending on the transmitted identification ID. In some cases where a lamprey was not detected with radiotracking or only detected with radiotracking without identifying the acoustic signal, the lamprey status was reported as unknown. As radiotracking was not continuously performed, and because of the lag time due to polymer digestion30, the method was not able to precisely inform about the exact location of the predation event. Further, due to the time gap existing between the occurrence of a predation event and its detection, the estimated times of the predation events we present here are likely overestimated, and the distances travelled by lampreys need to be considered with caution.

Each time a lamprey was interpreted as consumed (i.e. reception of a post-predation ID), we tried to capture the predator by angling without success. In some cases, we managed, however, to detect a catfish shape on the echo-sounder screen in the area of the predation signal. While the exact identity of predators was undetermined, predation is likely due to European catfish. Large individuals of another predatory fish inhabiting these rivers may consume adult sea lampreys (i.e. the Northern pike, whose maximal body size can reach 130 cm31). Nevertheless, predation by large pikes is probably exceptional, as the abundance of this species is very restricted in both rivers (Fig. 4a) compared to the abundance of European catfish (Fig. 4b). The other reported predator of sea lamprey in freshwaters, the Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra)18, is absent from the study area.

Observed field conditions in temperature (low temperatures, ranging between 9 to 14 °C in Dordogne and between 11 to 14 °C in Garonne) and tracking time (7 weeks in Dordogne and 3 weeks in Garonne) were compatible with conditions required to correctly identify predation events (i.e. short-term deployments and low water temperatures30). Concerning water levels, they were low compared to general mean hydrological conditions in March and April in both rivers. In Dordogne, mean daily discharges were 238 and 145 m3/s in March and April 2019, respectively (http://www.hydro.eaufrance.fr; station Lamonzie-Saint-Martin) whereas mean long-term daily discharges in this station averaged 376 and 330 m3/s in March and April (based on 60 years of measures). In Garonne, mean daily discharges were 351 and 396 m3/s in March and April 2019, respectively (station Tonneins) against averages of 876 and 844 m3/s in March and April in this station.

Lamprey tagging was conducted by Migado, an association in charge of monitoring and managing migratory fish species like the sea lamprey. The tagging procedure was in strict accordance with the National Guidelines for Animal Care of the French Ministry of Agriculture (decree n°2013–118) and the EU regulations concerning the protection of animals used for scientic research (Directive 2010/63/EU). The tagging procedure was approved by the ethical committee of the French region “Nouvelle Aquitaine” for fish and birds (C2EA73; authorization #2019022009545607). Previous field tests carried out in 2017 and 2018 using similar radio-transmitters on 116 lamprey individuals confirmed the low impact of the tagging procedure on lampreys.

Source: Ecology - nature.com