Kirch, P. V. Microcosmic histories: island perspectives on global change. Am. Anthropol. 99, 30–42 (1997).

Vitousek, P. M. Oceanic islands as model systems for ecological studies. J. Biogeogr. 29, 573–582 (2002).

Warren, B. H. et al. Islands as model systems in ecology and evolution: prospects fifty years after MacArthur‐Wilson. Ecol. Lett. 18, 200–217 (2015).

Steadman, D. W. et al. Asynchronous extinction of late Quaternary sloths on continents and islands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11763–11768 (2005).

Rick, T. C. et al. Origins and antiquity of the island fox (Urocyon littoralis) on California’s Channel Islands. Quat. Res. 71, 93–98 (2009).

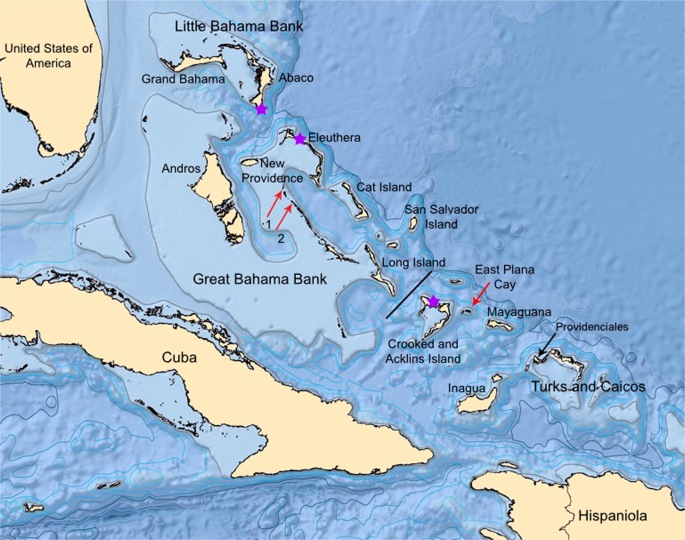

Steadman, D. W. et al. Exceptionally well-preserved late Quaternary plant and vertebrate fossils from a blue hole on Abaco, Bahamas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 19897–19902 (2007).

Steadman, D. W. & Franklin, J. Changes in a West Indian bird community since the late Pleistocene. J. Biogeogr. 42, 426–438 (2015).

Steadman, D. W. et al. Vertebrate community on an ice-age Caribbean island. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, E5963–E5971 (2015).

Oswald, J. A. & Steadman, D. W. The late Pleistocene bird community of New Providence, Bahamas. Auk. 135, 359–377 (2018).

Steadman, D. W., Pregill, G. K. & Olson, S. L. Fossil vertebrates from Antigua, Lesser Antilles: Evidence for late Holocene human-caused extinctions in the West Indies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 4448–4451 (1984).

Newsom, L. A. & Wing, E. S. On land and sea: Native American uses of biological resources in the West Indies (University of Alabama Press, 2004).

Cooke, S. B., Mychajliw, A. M., Southon, J. & MacPhee, R. D. E. The extinction of Xenothrix mcgregori, Jamaica’s last monkey. J. Mammal. 98, 937–949 (2017).

Upham, N. S. Past and present of insular Caribbean mammals: Understanding Holocene extinctions to inform modern biodiversity conservation. J. Mammal. 98, 913–917 (2017).

Hearty, P. J., Neumann, A. C. & Kaufman, D. S. Chevron ridges and runup deposits in the Bahamas from storms late in oxygen-isotope substage 5e. Quat. Res. 50, 309–322 (1998).

Steadman, D. W. & Franklin, J. Origin, paleoecology and extirpation of bluebirds and crossbills in the Bahamas across the last glacial-interglacial transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9924–9929 (2017).

Courcelle, M., Tilak, M.-K., Leite, Y. L. R., Douzery, E. J. P. & Fabre, P.-H. Digging for the spiny rat and hutia phylogeny using a gene capture approach, with the description of a new mammal subfamily. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 136, 241–253 (2019).

Woods, C. A., Borroto-Páez, R. & Kilpatrick, C. Insular patterns and radiation of West Indian rodents in Biogeography of the West Indies: patterns and perspectives (eds. Woods, C. A. & Sergile, F. E.) 333–351 (CRC Press, 2001).

MacPhee, R. D. E. Insulae infortunatae: Establishing the chronology of late Quaternary mammal extinctions in the West Indies in American megafaunal extinctions at the end of the Pleistocene (ed. Haynes, G.) 169–197 (Springer, 2009).

Goodall, P. M. P. A historical survey of research on land mammals in the Greater Antilles in Terrestrial mammals of the West Indies: contributions (eds. Borroto-Páez, R., Woods, C.A. & Sergile, F. E.) 3–10 (Florida Museum of Natural History, 2012).

Upham, N. S. & Borroto-Páez, R. Molecular phylogeography of endangered Cuban hutias within the Caribbean radiation of capromyid rodents. J. Mammal. 98, 950–963 (2017).

MacPhee, R. & Iturralde-Vinent, M. Origin of the Greater Antilles land mammal fauna, 1: New Tertiary fossils from Cuba and Puerto Rico. Am. Mus. Novit. 3141, 1–31 (1995).

MacPhee, R. D. E., Flemming, C. & Lunde, D. P. Last occurrence of the Antillean insectivoran Nesophontes: New radiometric dates and their interpretation. Am. Mus. Novit. 3261, 1–20 (1999).

Dávalos, L. M. & Turvey, S. T. West Indian mammals: the old, the new, and the recently extinct in Bones, clones, and biomes: The history and geography of Recent Neotropical mammals (eds. Patterson, B. D. & Costa, L. P.) 157–202 (University of Chicago Press, 2012).

Turvey, S. T. & Dávalos, L. Geocapromys brownii, Jamaican hutia. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T9001A12948823 (2008).

Turvey, S. T., Kennerley, R. J., Nuñez-Miño, J. M. & Young, R. P. The Last Survivors: current status and conservation of the non-volant land mammals of the insular Caribbean. J. Mammal. 98, 918–936 (2017).

Borroto-Páez, R. & Woods, C. A. Feeding habits of the capromyid rodents in Terrestrial mammals of the West Indies: contributions (eds. Borroto-Páez, R., Woods, C. A. & Sergile, F. E.) 221–228 (Florida Museum of Natural History, 2012).

Morgan, G. S., MacPhee, R. D. E., Woods, R. & Turvey, S. T. Late Quaternary fossil mammals from the Cayman Islands, West Indies. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 428, 1–79 (2019).

Clough, G. C. Current status of two endangered Caribbean rodents. Biol. Conserv. 10, 43–47 (1976).

Morgan, G. S. Taxonomic status and relationships of the Swan Island hutia, Geocapromys thoracatus (Mammalia: Rodentia: Capromyidae), and the zoogeography of the Swan Islands vertebrate fauna. Proc. Biol. Soc. Wash. 98, 29–46 (1985).

Morgan, G. S. Geocapromys thoracatus. Mamm. Species. 341, 1–5 (1989).

Clough, G. C. Biology of the Bahamian hutia, Geocapromys ingrahami. J. Mammal. 53, 807–823 (1972).

Allen, J. A. Description of a new species of Capromys from the Plana Keys, Bahamas. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 3, 329–336 (1891).

Brodkorb, P. Pleistocene birds from New Providence Island, Bahamas. Bull. Florida State Mus., Biol. Sci. 4, 349–371 (1959).

Olson, S. L. & Pregill, G. K. Introduction to the paleontology of Bahaman vertebrates. Smithson. contrib. paleobiol. 48, 1–7 (1982).

Lawrence, B. N. Geocapromys from the Bahamas. Occas. pap. Boston Soc. Nat. Hist. 8, 189–196 (1934).

Allen, G. M. Geocapromys remains from Exuma Island. J. Mammal. 18, 369–370 (1937).

Jordan, K. C. An ecology of the Bahamian hutia. PhD diss., University of Florida (1989).

Jordan, K. C. Ecology of an introduced population of the Bahamian hutia (Geocapromys ingrahami) in Terrestrial mammals of the West Indies: contributions (eds. Borroto-Páez, R., Woods, C. A. & Sergile, F. E.) 115–142 (Florida Museum of Natural History, 2012).

Berman, M. J., Gnivecki, P. L. & Pateman, M. P. The Bahama Archipelago in The Oxford handbook of Caribbean archaeology (eds. Keegan, W. F., Hofman, C. L., Rodríguez-Ramos, R.) 264–280 (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Keegan, W. F. & Hofman, C. L. The Caribbean before Columbus. (Oxford University Press, 2017).

Carlson, L. A. Aftermath of a feast: Human colonization of the Southern Bahamian Archipelago and its effects on the indigenous fauna. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL (1999).

LeFebvre, M. J., deFrance, S. D., Kamenov, G. D., Keegan, W. F. & Krigbaum, J. The zooarchaeology and isotopic ecology of the Bahamian Hutia (Geocapromys ingrahami): Evidence for Pre-Columbian anthropogenic management. PLOS ONE 14(9), e0220284 (2019).

LeFebvre, M. J., DuChemin, G., deFrance, S. D., Keegan, W. F. & Walczesky, K. Bahamian hutia (Geocapromys ingrahami) in the Lucayan realm: Pre-Columbian exploitation and translocation. Environ. Archaeol. 24, 115–131 (2019).

Steadman, D. W. et al. Late Holocene historical ecology: The timing of vertebrate extirpation on Crooked Island, The Bahamas. J. Island Coast. Arch. 12, 572–584 (2017).

Steadman, D. W., Albury, N. A., Mead, J. I., Soto-Centeno, J. A. & Franklin, J. Holocene vertebrates from a dry cave on Eleuthera Island, Commonwealth of The Bahamas. Holocene. 28, 806–813 (2017).

Clough, G. C. A most peaceable rodent. Natural History 82, 66–74 (1973).

Clough, G. C. Additional notes on the biology of the Bahamian hutia, Geocapromys ingrahami. J. Mammal. 55, 670–672 (1974).

Wing, E. S. Zooarchaeology of West Indian land mammals in Terrestrial mammals of the West Indies: contributions (eds. R Borroto-Páez, CA Woods, FE Sergile) 342–356 (Florida Museum of Natural History, 2012).

LeFebvre M. J. & deFrance, S. D. Animal management and domestication in the realm of Ceramic Age farming in The archaeology of Caribbean and circum-Caribbean farmers (6000 BC – AD 1500) (ed. Reid, B.) 149–170 (Routledge, 2018).

Hofreiter, M., Serre, D., Poinar, H. N., Kuch, M. & Paabo, S. Ancient DNA. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2(5), 353–9 (2001).

Gilbert, M. T. P. et al. Characterization of genetic miscoding lesions caused by postmortem damage. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72(1), 48–61 (2003).

Fabre, P.-H. et al. Mitogenomic phylogeny, diversification, and biogeography of South American spiny rats. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 613–633 (2017).

Rick, T. C. & Lockwood, R. Integrating paleobiology, archaeology, and history to inform biological conservation. Conserv. Biol. 27(1), 45–54 (2012).

Morgan, G. S. Fossil Chiroptera and Rodentia from the Bahamas, and the historical biogeography of the Bahamian mammal fauna in Biogeography of the West Indies: past, present, and future (Woods, C. A.) 685-740 (Sandhill Crane Press, 1989).

Yang, D. Y., Eng, B., Waye, J. S., Dudar, J. C. & Saunders, S. R. Technical note: Improved DNA extraction from ancient bones using silica-based spin columns. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 105, 539–43 (1998).

Yang, D. Y., Liu, L., Chen, X. & Speller, C. F. Wild or domesticated: DNA analysis of ancient water buffalo remains from north China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 35, 2778–2785 (2008).

Oswald, J. A. et al. 2,500-year-old aDNA from Caribbean fossil places an extinct bird (Caracara creightoni) in a phylogenetic context. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 140, 106576 (2019).

Jónsson, H., Ginolhac, A., Schubert, M., Johnson, P. L. F. & Orlando, L. mapDamage2.0: fast approximate Bayesian estimates of ancient DNA damage parameters. Bioinformatics 29, 1682–1684 (2013).

Castresana, J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 540–552 (2000).

Guindon, S. & Gascuel, O. A simple, fast and accurate method to estimate large phylogenies by maximum-likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52, 696–704 (2003).

Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R. & Posada, D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 9, 772 (2012).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML Version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–3 (2014).

Bouckaert, R. et al. BEAST 2.5: An advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLOS Comput. Biol. 15, e1006650 (2019).

Suzuki, Y., Tomozawa, M., Koizumi, Y., Tsuchiya, K. & Suzuki, H. Estimating the molecular evolutionary rates of mitochondrial genes referring to quaternary ice age events with inferred population expansions and dispersals in Japanese Apodemus. BMC Evol. Biol. 15, 187 (2015).

MacPhee, R. D. E., Iturralde-Vinent, M. A. & Gaffney, E. S. Domo de Zaza. An early Miocene vertebrate locality in south-central Cuba, with notes on the tectonic evolution of Puerto Rico and the Mona Passage. Am. Mus. Novit. 3394, 1–42 (2003).

Fabre, P.-H. et al. Rodents of the Caribbean: Origin and diversification of hutias unraveled by next-generation museomics. Biol. Lett. 10, 20140266 (2014).

Verzi, D. H., Vucetich, M. G. & Montalvo, C. I. Un nuevo Eumysopinae (Rodentia, Echimyidae) del Mioceno tardío de la provincia de La Pampa y consideraciones sobre la historia de la subfamilia. Ameghiniana 32, 191–195 (1995).

Olivares, A. I., Verzi, D. H., Vucetich, M. G. & Montalvo, C. I. Phylogenetic affinities of the late Miocene echimyid Pampamys and the age of Thrichomys (Rodentia, Hystricognathi). J. Mammal. 93, 76–86 (2012).

Rambaut, A., Drummond, A. J., Xie, D., Baele, G. & Suchard, M. A. Posterior summarisation in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. syy032 (2018).

Paradis, E. pegas: An R package for population genetics with an integrated–modular approach. Bioinformatics 26, 419–20 (2010).

Eakins, B. W. & Sharman, G. F. Hypsographic curve of Earth’s surface from ETOPO1, NOAA National Geophysical Data Center, Boulder, CO, https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/global/etopo1_surface_histogram.html (2012).

ESRI. ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10. Redlands, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute (2011).

Source: Ecology - nature.com