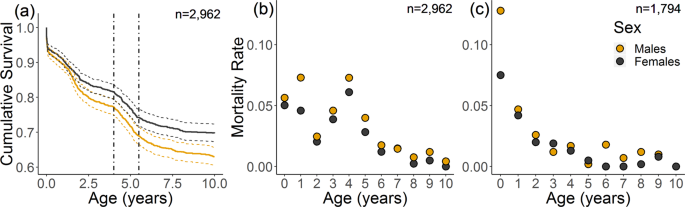

More than a quarter of Asian elephants in the world today are semi-captive, living in human care, and yet even the largest of these populations, the ~5,000 timber elephants of Myanmar, is not currently self-sustaining39. One of the most important factors limiting this population is high juvenile mortality4, a substantial proportion of which is likely linked to the taming procedure. For now, the taming process is necessary in this population for the safety of those working so closely with these dangerous animals12, but it is a source of human-elephant conflict which can be managed. Here, we show that mortality peaks around the taming age of four, rising by over 50% compared to age three, and it appears this is a symptom of their management, likely the taming procedure, as a similar peak is not observed in wild African elephants11. We pinpoint traits associated with increased mortality at these ages, which can be used to adapt management to protect vulnerable individuals.

Males generally experience higher juvenile mortality in this population9 and past studies of Asian elephants found males to be more at risk during human-elephant conflicts such as poaching and crop protection, but it is unknown whether differences exist during taming ages3,35. Males are assumed to pose more risk during the taming process (due to their larger size40 and tusks), and therefore one could expect harsher treatment41. However, our study showed that males were no more likely to die than females during the taming ages of 4.0–5.5. It is possible that sex becomes less important at times of high mortality. For example, it has been shown in the past that sex differences are also negligible during the year following capture in this population during which mortality rates are very high24, and primiparous mothers have been shown to suffer high losses of both sons and daughters in African elephants11. It is also likely that taming is a time when a larger body size is actually beneficial for survival, so this may explain why the sex difference is lessened at these ages.

Mortality risk often depends on an individual’s body size or condition, such as deaths due to infectious diseases, exhaustion, parasites or gastro-intestinal issues, which together made up over a half of taming age deaths (see Supplementary Information). There are many factors that could be interpreted, with caution, as proxies for an individual’s body size or condition. Calves born earlier in the year, who were therefore older during the taming period at the end of the year, and therefore generally larger40, were significantly less likely to die. Furthermore, offspring body size has been shown to correlate with birth order in other species42,43,44 including African elephants45, with first born individuals often being smaller. Calves in our study born to less experienced mothers were significantly more likely to die during taming ages, likely reflecting calves in worse condition. This is consistent with past findings in this population that first time mothers also had more still births and lower overall calf survival up to age five9, and also findings from wild African elephants that calves with low parity were more at risk11. Calves of older mothers could also be expected to show higher mortality for this reason, due to the senescence of older females46, however we found that calves born to older mothers experienced slightly higher mortality during specific taming ages, but this effect was not significant. This is consistent with recent findings in this population that maternal age does not necessarily dictate survival in the first five years, but rather their overall lifespan47.

There are many other factors that could be influencing mortality around the time of the taming process, other than taming itself. It is possible that social influences could be driving differences between individuals, with some coping better with being separated from their mother than others. For example, calves naturally separate themselves from their mothers over time and males stray more than females36, so the reduced mortality difference between males and females at taming age compared to other ages and the higher survival in relatively older calves could be linked to a smoother and more natural separation from their mother. Furthermore, mortality around the taming age of four may be linked to weaning as calves are separated from their mother at this time, and mortality in some species can increase following weaning due to dietary adjustments48. However, elephant calves begin to eat solid food at three to six months3,49, and by four years are reasonably practiced at foraging with both Asian and African elephant calves seen to wean around this age in the wild34,35. To reduce the possibility that the increase in mortality observed at four in the working elephants is a general weaning-age pattern, we compared our findings to data available on wild African elephants not subject to taming (similar data on wild Asian elephants is to our knowledge not available). If the increase in mortality was due to weaning, we would expect to see a similar mortality peak in the wild population of Amboseli elephants11, but this is not the case despite notably similar mortality patterns in the two populations at other ages.

It is also possible that certain diseases prevalent in juvenile elephants, such as EEHV, could be contributing to age-specific mortality around 4.0–5.5 years, either independently of, or exacerbated by, taming. Although only two of the 171 calf mortalities studied here were officially attributed to EEHV, diagnosis has likely been under-reported especially in the past17,50. EEHV deaths have been reported to peak between 0–4 years of age generally51 and in Thai semi-captive elephants, the median age of infection has been reported lower at <2.5 years17, although this could be due to transport and weaning at young ages in the Thai tourism industry. However, we do not expect this disease to be the driving force behind the dramatic increase in mortality at the age of four seen in Fig. 1b independently of taming, although the risk of infection could be exacerbated by taming. Most deaths in calves aged 4.0–5.5 years occurred in the months immediately following taming (January onwards), in contrast to deaths clustering towards the end of the hot season (April-May) at other ages (see Supplementary Fig. S1). This makes it likely that the mortality peak is linked to the taming period, whether directly or indirectly. It is important to reiterate that we do not discriminate between direct and indirect impacts of taming in this study, so any disease or environmental effect likely to disproportionately impact stressed animals may contribute to the increase in mortality risk during taming. Furthermore, although both logging schedules and variation in climate likely impact general mortality in this population, they are unlikely to specifically affect taming-age elephants as calves are not involved in logging operations until >17 years, nor would they explain the change in monthly distributions of deaths seen in Supplementary Fig. S152.

In terms of elephant management, Myanmar holds promise for future conservation, with the largest area of remaining natural habitat and ~5,000 semi-captive elephants of whom over half are centrally managed by the government who encourage breeding, factors often lacking in other countries6,7,53. The MTE have measures in place to minimize harm during taming, such as having a vet present for the whole period, daily walks, and more recently the gradual introduction of calves to human contact from the age of three months29. Promisingly, taming age mortality substantially decreased for calves born after 2000, consistent with reports of improved elephant treatment in the last two decades in this population26, and with more attention to individuals highlighted here as vulnerable, further improvements may be possible. It has been previously documented that calves of wild-caught mothers generally show increased infant mortality compared to calves of captive-born mothers in this population, especially in the year following their mother’s capture25. Although the chance of mortality at taming ages again reduced with increased time since mother’s capture, this trend and the effect of mother’s origin were not significant, which is encouraging considering over 40% of individuals in this population, across the study period, originate from the wild24.

Our interpretation that mortality differences according to birth order and calf age are linked to body size or condition has complex implications, as it concerns not only animal welfare, but also human safety. There is reluctance among elephant handlers to tame larger calves, as they pose more of a physical threat during times of close contact like taming, and the procedure can take longer, requiring more resources and money, and perhaps harsher measures41. Furthermore, the longer a calf stays with its mother, the longer she is kept from certain work tasks. Delaying taming would therefore require financial subsidies, which could be a major barrier in this population primarily driven by economic restraints rather than conservation, although there has been much focus recently on the latter6. The taming age of four in MTE elephants is already later than in other semi-captive populations, such as in Nepal, India and Thailand where taming generally occurs at age three54,55,56. Unfortunately, no comparable data exists from these populations on mortality risks during the taming process, with our study, to our knowledge, providing the first published estimates. We invite more studies into the effects of taming on Asian elephants across their range, as there are substantial differences between countries and even within countries that lack central management, and information from different perspectives could help us to further understand, and reduce, drivers of mortality. We also highlight the need for more study into population dynamics of wild Asian elephants to better inform comparisons to natural demographic parameters, which are for the moment largely lacking.

Now is an important time to address issues regarding taming, with largescale shifts within elephant management worldwide making change possible, to boost the survival of calves that are particularly vulnerable to taming risks26,57. The steep declines in mortality during taming in the MTE elephants over the last two decades are promising for the future of human-managed populations that are, for the moment, reliant on a degree of taming. In Myanmar, practices are changing, and managers sometimes recommend delayed or softer taming for certain female or orphaned calves. We recommend managers and those involved in taming worldwide consider adopting similar practises to these which have been coupled with reduced mortality, as well as considering the greater vulnerability of calves born to first-time mothers and those younger at the onset of taming. We urge for more studies across other populations and species to identify traits underlying mortality differences during periods of stress, be it due to anthropogenic or natural stressors, to inform management priorities.

Source: Ecology - nature.com