By bringing together diverse, spatially explicit datasets, we present a flexible methodology for identifying where land-sparing policies are most needed, and where they are most likely to succeed. We focus on Brazil, a country of exceptional global importance for both biodiversity conservation and agriculture, but the methods used here could be adapted for any region with adequate data, and could be adapted to analyse other metrics such as carbon storage and emissions. Our illustrative analyses are a step towards a more fine-grained understanding of the potential for land-sparing policies in practice, and of the constraints they face. Our results underline the considerable technical potential for land sparing in Brazil, in line with other recent work, but also highlight the importance of understanding and addressing a range of social and economic constraints2,3,34,35.

Our analyses can help inform where to focus efforts to support land sparing in policy and practice. Yield gaps are widespread across the country, and widest in pasture. Increasing the efficiency of cattle production on pasture provides the greatest opportunities for reducing land demand. Despite this, closing yield gaps on pasture would make only a small addition to Brazil’s food supply36. Yield gaps are proportionally far smaller on cropland, and in many places, current yields are already close to their potential. However, cropland (even just the seven crops analyzed here) has the potential to supply more additional food than is possible through animal agriculture. Production of meat and milk is inefficient, but in consequence, presents the greatest biophysical potential to spare land for nature if the right policies, norms and incentives are in place.

What might those mechanisms look like? To promote land sparing, they should include instruments such as zoning, economic incentives or disincentives, targeted extension, and certification to link conservation and production outcomes1. Such linkages could be incorporated into agricultural extension, infrastructure planning, rural credit programs, farmer networks, and certification schemes1,29. Several real-world examples suggest the form these might take in Brazil. For example, a combination of stringent forest protection and clustered development of agribusiness in Mato Grosso has been linked to increases in stocking rates of cattle and double-cropping of soybeans with maize and cotton35. Various initiatives in the Brazilian Amazon have worked with cattle ranchers to increase pasture yields by 30–170% through use of rotational grazing, legumes, and other pasture management techniques, while at the same time improving compliance with the Forest Code29. Interestingly, all of the eight municipalities in which these initiatives occurred had below-median additional production potential, and above-median biodiversity importance, alongside the constraint of low labor availability, suggesting that strengthing environmental compliance should be a higher priority for these initiatives than supporting yield increases. More widely, through a combination of law enforcement, property registration, supply-chain commitments, protected area expansion and financial instruments, Amazon deforestation was reduced by ~70% in the decade from 2004, while beef and soybean production continued to increase12,29,37. The policies, norms and incentives to deliver land sparing are complex, but are becoming better-understood.

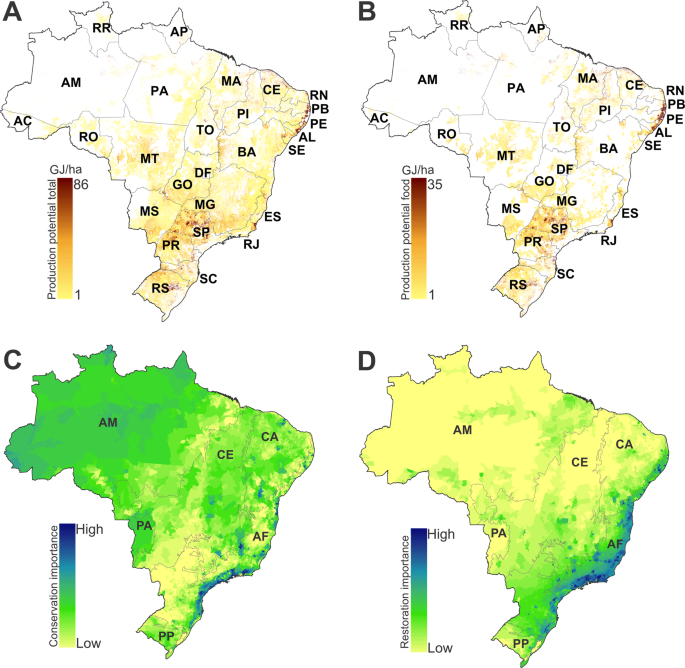

Our analysis points to the importance of finding the right scale at which to implement land sparing. We identified relatively few municipalities with both high potential to increase food production and low importance for biodiversity. More common were municipalities with low potential for increasing production and high biodiversity importance, or with high potential for both food production and biodiversity. This suggests that a strategy of focusing agricultural yield increases in some municipalities and conservation or restoration in others as part of a large-scale land sparing approach may not be sufficient. Instead, we suggest that conservation should be prioritized in some regions (such as the Pantanal), and municipality-level land-sparing policies developed in many others. In other words, coordinating both conservation and agricultural development within municipalities may be at least as important as large-scale segregation of conservation and farming.

We present a first attempt to identify and map some of the conditions that could help or hinder municipality-level land-sparing policies. These conditions, as well as conservation and agricultural needs, vary by municipality, calling for different strategies in different places. Areas where land-sparing initiatives are most likely to succeed are not necessarily those of highest production potential or conservation priority, but those where institutional constraints are minimal. In areas where constraints exist, efforts can be made to reduce their impact, through increasing access to technical advice, training the existing labor force, strengthening land tenure, monitoring and enforcing compliance with the Forest Code, and improving incentives to landowners for conservation measures such as private protected areas (Brazilian acronym: RPPNs). The data we synthesize here could be used in different ways by different actors to target such efforts to where they may be most successful.

Areas of high conservation importance are distributed across all of the country’s domains, from the Amazon to the Pampas, underlining the need for policies to extend beyond the forest domains that have hitherto received most attention19. The municipalities with the very highest levels of endemism and restoration priority were in the Atlantic Forest, as expected, but there were areas of exceptional importance elsewhere too, particularly in the Caatinga and Cerrado. Care is needed in interpreting these maps, as they are based on a limited set of taxa, emphasize endemism, and are influenced by biases in taxonomic and biogeographical knowledge38. However, we consider them a good starting point for identifying priorities, and an improvement over single-taxon maps of species richness.

The inherent inefficiency of livestock production also points to the value of demand-side measures, to reduce consumption of meat and milk and to shift diets towards plant-based alternatives39. On the supply side, increasing livestock productivity would do little to increase the food supply, but it could help to slow or reverse the expansion of agricultural area in Brazil if combined with “land-neutral agricultural expansion”38, adequate protection of native vegetation, and forest restoration40,41. Using methods such as integrating silviculture into livestock systems to restore degraded pastures (at least half of Amazon and Cerrado pastures42) could help to minimize the negative environmental effects of increasing yields. There is much interest in integrated crop–livestock–forestry systems in Brazil, but as yet relatively limited evidence for their productive and environmental benefits43. Incentives to increase crop and livestock yields are just one of the steps needed to spare land for nature26, and care must be taken not to encourage agricultural expansion through a rebound or backfire effect6.

Increasing the yields of export commodities such as soybeans and sugarcane is less likely to contribute towards the objective of sparing land for nature than increasing yields of domestically-consumed staple crops such as rice and wheat. Some technologies are less compatible with land sparing than others. For example, more efficient deforestation techniques44 will promote deforestation, while investments in existing farmed land (such as installing drip irrigation systems) are more likely to promote the consolidation of agricultural production on existing farmland. Limited labour availability could reduce the risk of leakage, but could also make it more difficult or expensive for farmers to adopt improved agricultural practices33.

Our datasets and analyses have various limitations. Large-scale agricultural and biodiversity datasets do not fully reflect local conditions. Our maps of biodiversity are only as complete as existing knowledge of species and their distributions, and other environmental outcomes, such as biomass, could also merit consideration. Municipalities are treated as units, but even within municipalities, there may be great variation in soil type, terrain and other variables. We averaged estimates of future production potential across multiple climate models, but only one trajectory will come to pass. Energy ouptut is an imperfect metric of food production, and our metric of contribution to domestic food supply goes only partway to taking account of beneficiaries and end-uses. As described in the Introduction, there is some evidence for the influence of the variables shown in Table 1 on land-use outcomes, but more is needed, and cut-offs (such as median values) for mapping them as constraints are arbitrary. Other variables such as poverty, population density, and government investment in social protection programs may also be important. To inform decision-making, all such variables will need to be considered in the context of local particularities, alongside the expected marginal costs and benefits of different conservation actions.

These limitations notwithstanding, our results indicate some promising ways forward for reconciling biodiversity conservation and agricultural production in Brazil, including reducing demand for meat and milk, restoring degraded pastures using methods such as integrated crop–livestock–forestry systems, shrinking the land area used for livestock, replacing some pasture with cropland, and strengthening efforts to protect and restore native vegetation. The results also help to identify where such efforts might be most effective, as well highlighting constraints in other parts of Brazil that will need to be overcome for land sparing to succeed. Our data and analyses can be adapted to inform conservation planning, assist NGO engagement with the agricultural sector, aid corporate sustainability efforts, and to develop policies, norms and incentives to link conservation and production outcomes within municipalities. With such efforts, Brazil could build on its existing achievements to become a world leader in reconciling biodiversity conservation and agricultural production.

Source: Ecology - nature.com