The D. suzukii population used in this study originated from ~50 flies that emerged from elderberries collected in September 2016 in northern Germany. Since then the flies had been kept at a population size of approx. 200 flies in custom-made population cages (22 litres). For egg collection, flies were offered thawed raspberries, and oviposited fruits were subsequently transferred to a standard Drosophila culture medium22. Larvae were incubated at 25 °C and emerging flies were released into a new population cage. Flies were fed with the decayed fruit/culture medium and crushed raspberries and had access to water.

Seven to ten-day old females, previously kept in the abovementioned population cages containing flies of the same age cohort were used in experiments 1 and 2. Prior to the experiments, every two days flies were given 15 to 20 thawed raspberries for oviposition. Thus, flies had no previous experience with blueberries, and competition for oviposition sites was expected to be intense. That is, compared to the situation in some treatments of the experiments, individual flies very likely did not experience egg limitation. In all experiments, the blueberries used were organically grown in Chile, carefully rinsed with water before further use and inspected for previous infestation and lesions.

Experiment 1 – Drosophila suzukii egg distributions as a function of variation in total fruit availability

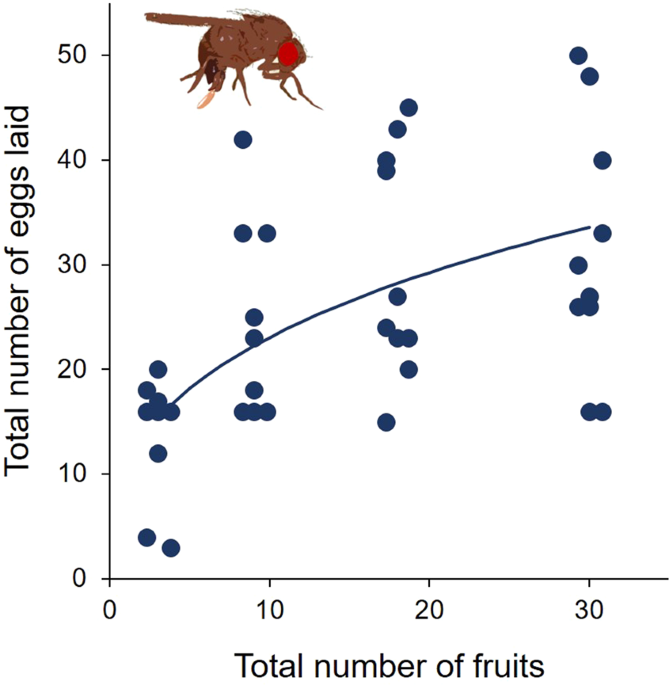

In a first experiment, we tested whether D. suzukii females have an oviposition preference for healthy host fruits (blueberries) given different degrees of resource availability. Resource availability was manipulated by offering individual female flies either 3, 9, 18 or 30 fruits. We assumed resource limitation to become more severe the fewer fruits were available. We did not use extraordinarily large and small fruits to prevent fruits size variation to have strong effects on the probability of fruit encounters and egg-laying decisions. Selected fruits were assigned randomly to the different treatments. To offer flies alternative fruit stages, fresh blueberries were wounded by cutting off the calyx and some of the surrounding fruit skin with a scalpel, exposing an area of exposed fruit flesh of ca. 1 cm diameter. Half of the wounded berries were left untreated, whereas the other half was inoculated with an aqueous yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, strain DSM 70449) suspension (1 million yeast cells per 10 µl per fruit) to simulate a fermenting stage. Fruits were prepared approx. five hours prior to their use in the experiments. In each experimental arena, one third of the fruits offered was either ‘healthy’, ‘wounded’ or ‘fermenting’; e.g., when flies were offered 18 fruits in total, 6 were healthy, 6 wounded, and 6 fermenting. According to randomly assigned positions in a lattice, fruits were arranged in equal distances on a wet sponge cloth (cellulose/cotton blended fabric, Spontex, Germany) provided with holes to ensure that the wound remained on the upper side and to provide flies with water during the trials. The fruits were offered in 1 litre plastic boxes (arenas) (~6 × 11.5 × 17.5 cm, euroboxx, Germany) that were closed with a translucent lid. Around 4 p.m. single female D. suzukii females were released into the arenas. Initially, 15 arenas were prepared and incubated at a 16-hour light cycle and 25 °C ± 0.5. On the following day around 10 a.m. the flies were removed and the number of eggs per blueberry were counted. As we excluded counts were flies laid fewer than four eggs in total, the number of replicates was reduced accordingly (see Fig. 2).

The proportion of eggs single females allocated to the different fruit categories were used to test the null hypothesis that the status of the fruits – healthy, wounded or fermenting – had no influence on how the eggs were distributed, i.e. that on average 1/3 of the eggs laid were allocated to each fruit category. We explored this hypothesis by testing whether the proportion of eggs oviposited in healthy fruits changed as a function of total resource availability. This was achieved by applying a binomial generalised linear model (GLM) in R 3.3.2, for which we specified a logit link function. To test for an explicit deviation from 1/3 of eggs allocated to healthy fruits, we used the offset function to fix the intercept at logit(1/3); note that otherwise the null hypothesis is logit(1/2), which equals zero. For the data from experiment 2, the procedure was used to test for deviation from 1/2, 1/4, and 1/6, that is the expected relative abundance of eggs allocated to healthy fruit under the null hypothesis.

To explore the patterns of fruit use on the basis of presence/absence of eggs, i.e. proportion of fruits used as oviposition sites, we applied a generalised linear mixed model (glmer) in R with a logit link function. To test whether the proportion of fruits used for oviposition changed with total resource availability and as a function of the status of the fruits, we included the interaction term for resource availability (total number of fruits) and fruits status in the model.

Experiment 2 – Drosophila suzukii egg distributions as a function of variation in the proportional abundance of healthy fruits

By manipulating the proportion of healthy fruits whilst keeping the total resource availability constant (12 blueberries), we aimed at testing whether the flies’ oviposition preference changes with the relative abundance of healthy fruits. This approach allows evaluating to what extent preference reflects specialisation on a certain type of host fruits12. Because in Experiment 1 wounded blueberries turned out to be the least preferred fruit category, we decided to reduce the proportion of healthy fruits embedded in a matrix of wounded blueberries by using following ratios of healthy/wounded fruits, respectively: 6/6, 4/8 and 2/10. The experimental procedure followed the same described in Experiment 1. Initially, 12 arenas were prepared, however, as we again excluded counts were flies laid fewer than four eggs in total, the number of replicates was reduced accordingly (see Fig. 4).

Experiment 3 – Effect of host fruit status and intraspecific competition on the developmental success of Drosophila suzukii larvae

To obtain a range of egg densities on wounded and intact fruits, artificially wounded and healthy blueberries were exposed for differing durations to the flies in a population cage. Only egg densities of ≤20 eggs per gram were included in the analysis. In total, we obtained a range of egg densities in 111 healthy and 111 wounded fruits. After counting the eggs, berries were weighed and subsequently placed individually into 30 ml polystyrol rearing tubes (8 cm height, 3.5 cm diameter, K-TK, Germany) that were sealed with foam stoppers. The fruits were incubated at 25 °C ± 0.5, a 16-hour light cycle and ambient humidity in a thermostatic cabinet (Liebherr, Thermostatschrank, ET619-4/135 litre, Germany), and checked daily for emergence for a maximum of 25 days. Adults were frozen on the day of emergence, dried in a silica gel desiccator for eight days to constant weight and sexed under the microscope. For each blueberry, we weighed males and females separately (SE2 ultra-microbalance, Sartorius, Germany), and calculated the mean adult dry weight, i.e. the total weight of females, or males, divided by the number of flies measured for each sex. The developmental time was taken as the median number of days between oviposition (day 1) and the emergence of adult flies per blueberry.

We used generalised linear models (GLMs) to investigate the relation between the two fixed effects initial egg density (eggs per gram blueberry) and blueberry treatment (intact versus wounded fruits) and each response variable (survivorship, mean adult dry weight, median development time). As Drosophila is known to exhibit sexual size dimorphism23, sex was added as fixed effect in the analysis of adult dry weight. Development time as well as adult dry weight were modelled using a GLM with Gamma error structure and log link, whereas for survival data we specified a binomial GLM with a logit link function and corrected for under-dispersion. We performed stepwise backward eliminations of non-significant terms, starting with the most complex interactions (Anova function in car package24). Data were analysed in R 3.2.325.

Source: Ecology - nature.com