Dirzo, R. & Raven, P. H. Global state of biodiversity and loss. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 28, 137–167 (2003).

Bonan, G. B. Forests and climate change: Forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 320, 1444–1449 (2008).

Poorter, L. et al. Diversity enhances carbon storage in tropical forests. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 24, 1314–1328 (2015).

Chave, J. Neutral theory and community ecology. Ecology Letters 7, 241–253 (2004).

Jarzyna, M. A. & Jetz, W. Taxonomic and functional diversity change is scale dependent. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–6 (2018).

Sullivan, M. J. P. et al. Diversity and carbon storage across the tropical forest biome. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–12 (2017).

Liang, J. et al. Positive biodiversity-productivity relationship predominant in global forests. Science 354 (2016).

Ferreira, J. et al. Carbon-focused conservation may fail to protect the most biodiverse tropical forests. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 744–749 (2018).

Tilman, D. The ecological consequences of changes in biodiversity: A search for general principles. Ecology 80, 1455–1474 (1999).

Tilman, D., Isbell, F. & Cowles, J. M. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 45, 471–493 (2014).

Fauset, S. et al. Hyperdominance in Amazonian forest carbon cycling. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–2 (2015).

Ter Steege, H. et al. Hyperdominance in the Amazonian tree flora. Science 342, 1243092 (2013).

Safi, K. et al. Understanding global patterns of mammalian functional and phylogenetic diversity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 366, 2536–2544 (2011).

Bunker, D. E. Species Loss and Aboveground Carbon Storage in a Tropical Forest. Science 310, 1029–1031 (2005).

Figueiredo, F. O. G. et al. Beyond climate control on species range: The importance of soil data to predict distribution of Amazonian plant species. J. Biogeogr. 45, 190–200 (2018).

Prada, C. M. et al. Soils and rainfall drive landscape-scale changes in the diversity and functional composition of tree communities in premontane tropical forest. J. Veg. Sci. 28, 859–870 (2017).

Fayolle, A. et al. Geological substrates shape tree species and trait distributions in African moist forests. Plos One 7, e42381 (2012).

Reich, P. B. The world-wide ‘fast-slow’ plant economics spectrum: A traits manifesto. J. Ecol. 102, 275–301 (2014).

Quesada, C. A. & Lloyd, J. Soil–Vegetation Interactions in Amazonia. In: Interactions Between Biosphere, Atmosphere and Human Land Use in the Amazon Basin. (eds. Nagy, L., Forsberg, B. & Artaxo, P.) 267–299 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2016).

Bloom, A. J., Chapin, F. S. & Mooney, H. A. Resource limitation in plants – an economic analogy. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 363–392 (1985).

Rowland, L. et al. The response of tropical rainforest dead wood respiration to seasonal drought. Ecosystems 16, 1294–1309 (2013).

Fauset, S. et al. Drought-induced shifts in the floristic and functional composition of tropical forests in Ghana. Ecol. Lett. 15, 1120–1129 (2012).

Quesada, C. A. et al. Basin-wide variations in Amazon forest structure and function are mediated by both soils and climate. Biogeosciences 9, 2203–2246 (2012).

Phillips, O. L. et al. Drought sensitivity of the amazon rainforest. Science 323, 1344–1347 (2009).

Brienen, R. J. W. et al. Long-term decline of the Amazon carbon sink. Nature 519, 344–348 (2015).

Johnson, M. O. et al. Variation in stem mortality rates determines patterns of above-ground biomass in Amazonian forests: implications for dynamic global vegetation models. Glob. Chang. Biol. 22, 3996–4013 (2016).

Ter Steege, H. et al. Continental-scale patterns of canopy tree composition and function across Amazonia. Nature 443, 444–447 (2006).

Galbraith, D. et al. Residence times of woody biomass in tropical forests. Plant Ecology and Diversity 6, 139–157 (2013).

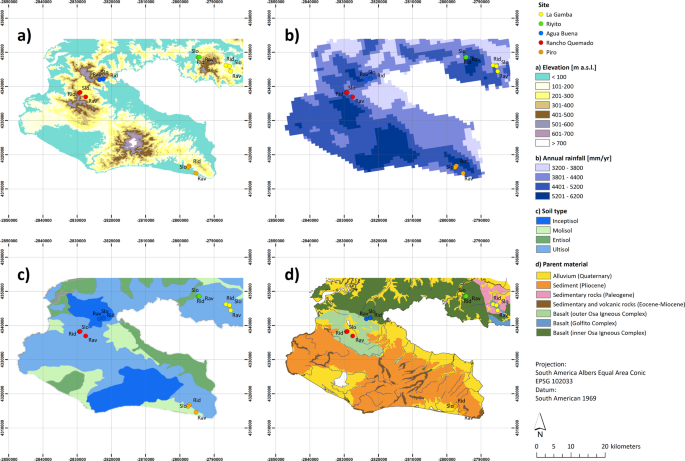

Taylor, P. et al. Landscape-scale controls on aboveground forest carbon stocks on the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica. Plos One 10, e0126748 (2015).

Hofhansl, F. et al. Sensitivity of tropical forest aboveground productivity to climate anomalies in SW Costa Rica. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 28, 1437–1454 (2014).

Slik, J. W. et al. Phylogenetic classification of the world’s tropical forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 1837–1842 (2018).

Fricker, G. A., Wolf, J. A., Saatchi, S. S. & Gillespie, T. W. Predicting spatial variations of tree species richness in tropical forests from high-resolution remote sensing. Ecol. Appl. 25, 1776–1789 (2015).

Saatchi, S. S. et al. Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 9899–9904 (2011).

Rödig, E., Cuntz, M., Heinke, J., Rammig, A. & Huth, A. Spatial heterogeneity of biomass and forest structure of the Amazon rain forest: Linking remote sensing, forest modelling and field inventory. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 26, 1292–1302 (2017).

Jucker, T. et al. Topography shapes the structure, composition and function of tropical forest landscapes. Ecology Letters 21, 989–1000 (2018).

Werner, F. A. & Homeier, J. Is tropical montane forest heterogeneity promoted by a resource-driven feedback cycle? Evidence from nutrient relations, herbivory and litter decomposition along a topographical gradient. Funct. Ecol. 29, 430–440 (2015).

Gray, M. Geodiversity: developing the paradigm. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 119, 287–298 (2008).

Prada, C. M. & Stevenson, P. R. Plant composition associated with environmental gradients in tropical montane forests (Cueva de Los Guacharos National Park, Huila, Colombia). Biotropica 48, 568–576 (2016).

Arellano, G., Cala, V. & Macía, M. J. Niche breadth of oligarchic species in Amazonian and Andean rain forests. J. Veg. Sci. 25, 1355–1366 (2014).

Fayolle, A. et al. Patterns of tree species composition across tropical African forests. J. Biogeogr. 41, 2320–2331 (2014).

Grau, O. et al. Nutrient-cycling mechanisms other than the direct absorption from soil may control forest structure and dynamics in poor Amazonian soils. Sci. Rep. 7, 45017 (2017).

Soong, J. L. et al. Soil properties explain tree growth and mortality, but not biomass, across phosphorus-depleted tropical forests. Sci. Rep. 10, 2302, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58913-8 (2020).

Kraft, N. J. B., Metz, M. R., Condit, R. S. & Chave, J. The relationship between wood density and mortality in a global tropical forest data set. New Phytol. 188, 1124–1136 (2010).

Chave, J. et al. Towards a worldwide wood economics spectrum. Ecol. Lett. 12, 351–366 (2009).

Homeier, J., Breckle, S. W., Günter, S., Rollenbeck, R. T. & Leuschner, C. Tree diversity, forest structure and productivity along altitudinal and topographical gradients in a species-rich Ecuadorian montane rain forest. Biotropica 42, 140–148 (2010).

Levine, N. M. et al. Ecosystem heterogeneity determines the ecological resilience of the Amazon to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 793–797 (2016).

Sakschewski, B. et al. Leaf and stem economics spectra drive diversity of functional plant traits in a dynamic global vegetation model. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 2711–2725 (2015).

Muelbert, A. E. et al. Compositional response of Amazon forests to climate change. Global Change Biology 25, 39–56, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14413 (2019).

Falster, D. S., Brännström, Å., Westoby, M. & Dieckmann, U. Multitrait successional forest dynamics enable diverse competitive coexistence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E2719–E2728 (2017).

Gilbert, L. E. et al. The Southern Pacific Lowland Evergreen Moist Forest of the Osa Region. In Costa Rican Ecosystems (ed. Kappelle, M.) 360–411 (University Chicago Press, 2016).

Quesada, F. J., Jiménez-Madrigal, Q., Zamora-Villalobos, N., Aguilar-Fernández, R. & González-Ramírez, J. Árboles de la Península de Osa. (Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad, 1997).

Weissenhofer, A. et al. Ecosystem diversity in the Piedras Blancas National Park and adjacent areas (Costa Rica), with the first vegetation map of the area. In: Natural and cultural history of the Golfo Dulce region, Costa Rica. Stapfia 88, zugleich Kataloge der Oberösterreichischen Landesmuseen NS 80 (2008).

Lobo, J. et al. Effects of selective logging on the abundance, regeneration and short-term survival of Caryocar costaricense (Caryocaceae) and Peltogyne purpurea (Caesalpinaceae), two endemic timber species of southern Central America. For. Ecol. Manage. 245, 88–95 (2007).

Pérez, S., Alvarado, A. & Ramírez, E. Manual Descriptivo del Mapa de Asociaciones de Subgrupos de Suelos de Costa Rica. San José, Costa Rica: Oficina de Planificación Sectorial Agropecuario, IGN/MAG/FAO. Escala 1:200,000. (1978).

Herrera, W. Climate of Costa Rica. In: Costa Rican Ecosystems. (eds. Maarten Kappelle, M. & Lobo, R. G.) The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-12164-2 (e-book), https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226121642.001.0001 (2016).

Karger, D. N. et al. Climatologies at high resolution for the earth’s land surface areas. Sci. Data 4, 170122 (2017).

Chave, J. et al. Improved allometric models to estimate the aboveground biomass of tropical trees. Glob. Chang. Biol. 20, 3177–3190 (2014).

ASTER. Global Digital Elevation Map, https://doi.org/10.5067/ASTER/ASTGTM.002 (2009).

Clark, D. B. & Clark, D. A. Landscape-scale variation in forest structure and biomass in a tropical rain forest. For. Ecol. Manage. 137, 185–198 (2000).

Alder, D. & Synnott, T. Permanent sample plot techniques for mixed tropical forest. (University of Oxford, 1992).

Malhi, Y. et al. An international network to monitor the structure, composition and dynamics of Amazonian forests (RAINFOR). J. Veg. Sci. 13, 439–450 (2002).

Peacock, J., Baker, T. R., Lewis, S. L., Lopez‐Gonzalez, G. & Phillips, O. L. The RAINFOR database: monitoring forest biomass and dynamics. J. Veg. Sci. 18, 535–542 (2007).

Zanne, A. E. et al. Data from: Towards a worldwide wood economics spectrum. Dryad Digital Repository. Dryad 235, 33 (2009).

Réjou-Méchain, M., Tanguy, A., Piponiot, C., Chave, J. & Hérault, B. Biomass: an r package for estimating above-ground biomass and its uncertainty in tropical forests. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 1163–1167 (2017).

Martin, A. R. & Thomas, S. C. A reassessment of carbon content in tropical trees. Plos One 6, e23533 (2011).

Lopez-Gonzalez, G., Lewis, S. L., Burkitt, M. & Phillips, O. L. ForestPlots.net: a web application and research tool to manage and analyse tropical forest plot data. J. Veg. Sci. 22, 610–613 (2011).

Brundrett, M. C. Mycorrhizal associations and other means of nutrition of vascular plants: Understanding the global diversity of host plants by resolving conflicting information and developing reliable means of diagnosis. Plant and Soil 320, 37–77 (2009).

Smith, S. E. & Read, D. J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. (Academic Press, 2008).

Valverde-Barrantes, O. J., Freschet, G. T., Roumet, C. & Blackwood, C. B. A worldview of root traits: the influence of ancestry, growth form, climate and mycorrhizal association on the functional trait variation of fine-root tissues in seed plants. New Phytol. 215, 1562–1573 (2017).

Evett, S. R., Schwartz, R. C., Tolk, J. A. & Howell, T. A. Soil profile water content determination: spatiotemporal variability of electromagnetic and neutron probe sensors in access tubes. Vadose Zo. J. 8, 926–941 (2009).

Hood-Nowotny, R., Umana, N. H.-N., Inselbacher, E., Oswald- Lachouani, P. & Wanek, W. Alternative methods for measuring inorganic, organic, and total dissolved nitrogen in soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 74, 1018–1027 (2010).

Peña, E. A. & Slate, E. H. Global Validation of Linear Model Assumptions. Journal of the American Statistical Association 101, 341–354 (2006).

Fox, J. Teacher’s Corner: structural equation modeling with the sem package in R. Struct. Equ. Model. 13, 465–486 (2006).

Lefcheck, J. S. PiecewiseSEM: Piecewise structural equation modelling in R for ecology, evolution, and systematics. Methods Ecol Evol. 7, 573–579, https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12512 (2015).

Burnham, K. P., Anderson, D. R. & Huyvaert, K. P. AIC model selection and multimodel inference in behavioral ecology: Some background, observations, and comparisons. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 65, 23–35 (2011).

Colman, B. P. & Schimel, J. P. Drivers of microbial respiration and net N mineralization at the continental scale. Soil Biol. Biochem. 60, 65–76 (2013).

R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (2017).

Schepaschenko, D. et al. The Forest Observation System, building a global reference dataset for remote sensing of forest biomass. Sci. data 6, 198 (2019).

Buchs, D. M. et al. Late Cretaceous to miocene seamount accretion and mélange formation in the osa and burica peninsulas (Southern Costa Rica): Episodic growth of a convergent margin. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 328, 411–456 (2009).

Open Source Geospatial Foundation. QGIS Geographic Information System Open Source. (2008).

Nakagawa, S. & Schielzeth, H. A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed‐effects models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 4(2), 133–142 (2013).

Source: Ecology - nature.com