Standardised surveys in australia

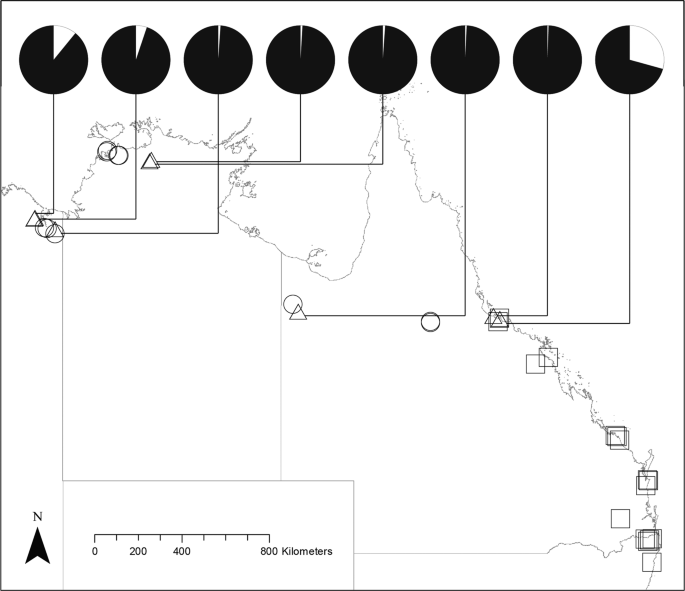

We quantified the abundance of cane toads by day and by night at sites along two continent-scale transects, each covering the full 84-year timespan of the toad invasion chronosequence in Australia (Table 1). The “east coast transect” (surveyed October 2017 to April 2018) consists of 16 sites running north-south, beginning near Townsville (close to the original release locations in 1935) and extending down the east coast of Australia to the southern invasion front in northern New South Wales. We focused our surveys at campsites in national parks and reserves and the surrounding temperate woodland. We also surveyed 18 sites along the toads’ trajectory of invasion east-west across the wet/dry tropics (the tropical transect, January to May 2019) between Townsville (as above) and Oombulgurri (recently invaded) in Western Australia. Each tropical site bordered a riparian area (river, dam, etc) and consisted of floodplain and tropical woodland savannah habitats.

Each site was surveyed over two sessions for a total of five days, with each survey session lasting two or three days. For logistical reasons up to three sites were surveyed concurrently, in randomised order to avoid latitudinal, longitudinal and seasonal bias. We also randomised the order that grouped sites were surveyed each day to remove time-of-day bias. We combined active search surveys and baited remote-sensing camera stations to estimate the number of cane toads and determine their times of activity.

Active search surveys

All toads encountered during surveys were recorded on mobile application software (Sightings v1.01). Survey effort was standardised (1 h/survey). Diurnal surveys were conducted on sunny days with maximum air temperature above 23 °C, and nocturnal surveys were conducted on dry nights with temperatures above 17 °C. Survey protocols differed slightly between transects due to targeting different varanid lizards in a concurrent project. The east coast transect sites were surveyed three times per day: morning (0800–1200 EST), afternoon (1200–1845 EST) and night (1845–0030). Each survey was partitioned into a 15-minute active-search on foot around target campsites, and a 45-minute active-search along a 5 km transect by vehicle through surrounding bushland. The tropical transect sites also were surveyed three times per day: morning (beginning 30 min after sunrise), afternoon (commencing three hours before sunset) and night (beginning 30 min after sunset). One-hour morning active search surveys were conducted on foot along a two km transect near focal waterbodies (rivers, creeks, dams, lagoons and billabongs). The afternoon and night surveys both involved a 30-min active search survey on foot (~1 km) and 30-min active survey along a five-km transect by vehicle (car or quad bike).

We sampled a subset of toads during each nocturnal survey. We sexed, weighed (g), and measured snout-urostyle length (“SUL”, to nearest 0.1 mm) of 962 adult toads, then gave an identifying toe clip prior to release at their point of capture. To avoid pseudoreplication, we excluded all recaptures from analysis. Body condition was calculated as a scaled mass index using the formula Mi * (L0/Li)^bSMA, with Mi and Li as the mass and length of the individual, L0 as the mean body length, and bSMA as the slope of the sex specific standard major axis log-log regression of mass by SUL for measured adults7.

Remote camera surveys

We deployed eight remote-sensing cameras (Scoutguard SG560K) and bait stations at each site. Cameras at east coast sites were positioned in two 100 m grids, one surrounding focal campsites and the other in bushland two km away, and were deployed for 48 hours (total 16 trap days/nights per site). Cameras at tropical transect sites were positioned near waterbodies along the active search survey transect, spaced at least 100 m apart, and deployed for two sessions lasting 48 and 72 h (total 40 trap days/nights per site).

Cameras were positioned on trees at a height of 40 cm, oriented towards the south, and placed in areas shaded by canopy cover where possible. A bait containing one chicken neck (east coast transect) or 80 g of sardines in oil (tropical transect) was placed one m from the camera in a PVC cannister attached to star picket at a height of 30 cm (such that it was non-consumable by vertebrate predators). Additional consumable baits were added around the base of most bait stations. Most sites (10/16) along the east coast transect had a cracked chicken egg placed on the ground at half of the bait stations (for a concurrently-run behavioural experiment). All bait stations deployed at tropical transect sites had one chicken egg (with small crack in the shell to release olfactory cues) placed at the base of the picket. A sardine and a cane toad leg (collected from road-killed cane toads and washed in water, frozen, and thawed 2 hours prior to deployment) were placed 30 cm to either side of the picket and covered with a plastic lid with mesh window (20 × 27 cm), with the position of sardine and toad leg randomised. Video footage showed toads feeding on the invertebrates that were attracted to both consumable and non-consumable baits.

Each camera was set to record one minute of video when triggered. Many videos contained images of more than one toad, and given the video resolution, we could not confidently identify individual toads across multiple videos. Our abundance estimates used a 30-minute event period to determine the number of active toads. When an animal was first detected on video, we reviewed videos from the next 30 minutes, and the video with the highest number of simultaneously visible toads within the timeframe was used as our abundance count for that period. Finally, we classified each toad as either diurnal (sighted or filmed between sunrise and sunset) or nocturnal (detected at night).

Radiotelemetry in French Guiana

We radio-tracked 34 cane toads at four sites (two coastal beach sites and two within the Amazon rainforest) in French Guinea between Aug and Sep 2017 in order to quantify toad activity in their native range. We hand-captured 10 toads at each site (except one rainforest site at Kaw Fourgassier, where only 4 toads were found), measured and weighed them, and determined their sex based on morphology (skin rugosity, color, the presence of nuptial pads) and male-specific “release calls”. We then attached radio-transmitters (Holohil PD-2, ~3.5 g, <5% of toad mass) to cotton twine waist-belts. Toads were equipped and released at their point of capture within 15 min of capture.

We then located each animal every day (between sunrise and sunset) for five days. During that period, each toad was also located on three nights (2000 to 0100). At the end of this sampling period the radio-transmitters were removed. Three toads at one site (the beach site of Montjoly) either dropped their transmitters or moved to inaccessible private land during the survey, so we had fewer observations for these individuals. Each time a toad was located, it was scored as either “inactive” or “active”. A toad was considered inactive if it was crouched or nestled within a refuge site (e.g. under thick vegetation or within a crevice). Body condition was calculated using the same scaled mass index described above (as estimated from a dataset of 240 adult toads measured in French Guiana in Aug-Sep 2017).

Source: Ecology - nature.com