Significance of plant diversity threat assessment and conservation in Tajikistan

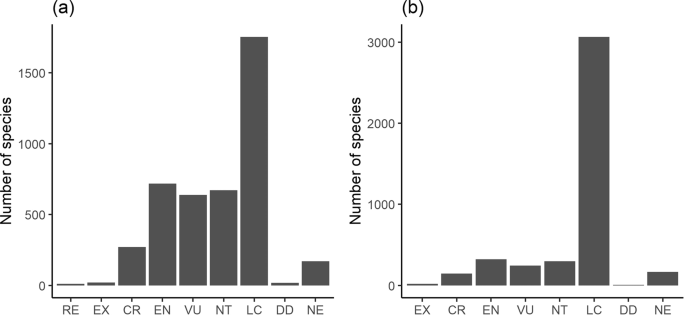

After the exclusion of anthropophytes, in total 4,160 species and subspecies have been assessed, which is a sample of around 50% of native species of Middle Asian flora (including Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan). This figure includes 1,273 exclusive endemics of Tajikistan, from which 20 are globally extinct and 144 critically endangered. As only twelve species from Tajikistan are included in the IUCN global red listing (6 CR, 3 EN and 3 VU, additionally 2 NT, 18 DD47), these numbers indicate the degree of under investigation of the conservation status in this valuable area of the world. This difference is particularly striking if we compare this region to other countries located in other biodiversity hotspots. In Italy, for example, 108 species were assessed to the CR, EN and VU categories, in India – 398 species, and in Indonesia – 481 species1. The Tajik’s natural heritage is under severe threat from climate change, habitat fragmentation and degradation caused by intensive grazing, population growth and unsustainable use of natural resources. All these phenomena and human activities have to be reflected in the threat status of the country flora, raising the numbers of endangered and vanished species in Tajikistan.

Human population density – a prime suspect responsible for the loss of plant diversity?

The human population of the country is still increasing; since the middle of the last century this has been about six-fold48 and this can have a serious impact on the biodiversity49. Simultaneously the pastoral economy and the number of livestock has increased significantly50. Currently, in Tajikistan, 160,000 people depend on livestock production, whereas the potential carrying capacity of the area is between 3 and 5 times lower51. Livestock farming and grazing is highlighted as a major threat to vascular plants in many countries, particularly those with a pastoral culture (e.g. Bilz et al.52). One of the highly fragile subregions that face extinction (EX, RE categories) are the two river valleys of Syr-Daria (Prisyrdarian) and upper Pyandzh. Both are intensively used for agriculture, and natural habitat types have suffered significantly in the last millennia.

Comparing the extinct taxa with the threatened ones (CR + EN + VU), some key differences emerge. Considering critically endangered, endangered and vulnerable plants, the larger subregions such as West Pamirian B, South Tajikistanian A and Kuraminian reveal the highest changes; these regions have a great number of habitat types, high diversity of plant species and are still considerably changed by human population. Human activity in these areas consists not only of agriculture but also mining and grazing. An extensive part of the land – particularly in the South Tajikistanian subregion – is urbanised. In the cases of the most natural regions, such as the East Pamirian and Alaian, the high proportion of threatened plants is influenced by the considerable uniqueness of its flora and the great number of species that occur exclusively in these regions (15.3% and 8.8% of unique species in the subregion, occupying respectively the first and third position in the country; Fig. S7). The same pattern is observed in the South Tajikistanian C and A, Kuraminian and Prisyrdarian regions, with 11.2%, 5.6%, 7.8% and 6.4% of unique species, respectively. With regard to the EOO criterion, they gain a higher risk of extinction in the country (Fig. 2b).

Traditionally, mountain agro-pastoralism in Central Asia has been based on altitudinal transhumance, connected with livestock seasonal mobility up and down the slopes that allows for regrowth of pasture plants and is important for vegetation conservation50,51. Nowadays, privatisation of livestock is leading to changes in herding patterns; due to economic problems (including the high cost of transport and the poor condition of the roads), livestock are no longer moved to the more distant and highest pastures for summer grazing and stay longer in the valleys and plains50,51. It is possible that these changes have influenced the relationship observed by us, i.e. that the highest number of threatened species (CR + EN) is associated with lowlands and colline zones (Fig. 3).

The influence of the density of settlements is also apparent when we observe the elevation pattern of the threatened plants’ share. The lowlands, valley bottoms and winter pastures are the most impacted in terms of flora withdrawal (Fig. 3). For critically endangered and endangered taxa, the threshold altitude at which the share is higher than average is at ca. 3,000–3,200 m a.s.l., and for vulnerable taxa not much higher. This reflects the distribution of human population and, to some extent, the transformations of the habitats (Fig. S6).

When looking at the habitat requirements of extinct taxa, it is clear that the forest and shrub species are the most impacted (Fig. 4a), particularly those located in the upper montane belt just below the tree line. This can be related to overgrazing of forests and intensive, however irregular, forestry. A decrease in fuel and coal supply resulted in their price rise, hence the people are forced to use slow-growing shrubs for heating and cooking51. Around 50% of the forests have disappeared in the past 100 years in Tajikistan, causing massive soil erosion and increased risk of landslides. Several types of riverside forests, e.g. stands of Fraxinus sogdiana, Populus pruinosa, Platanus orientalis, have almost entirely vanished. This, in combination with soil erosion and overgrazing, strongly hampers the reestablishment of tree stands. Grazing often leads to denudation and soil degradation and consequently to desertification53, which almost excludes the potential recovery of natural forest vegetation and fails to sustain the populations of forest taxa. The second group most affected is grassland flora along all the altitudinal belts (from colline dry meadows up to the alpine swards and forbs). In this case, the main factor responsible is connected with overgrazing.

Climate change vulnerability

The mountains of the Pamir-Alai are particularly sensitive to climate change due to the low adaptive capacity of its ecosystems29. Projections suggest a significant increase in temperature along with rainfall decline during the spring, summer and autumn seasons54. This, in combination with the drop of shepherding efficiency, may lead to further degradation of the vegetation cover. Moreover, desertification causes considerable threats to Tajik flora37 as the average temperature in the southern regions of the country rises by ca. 1 °C. Climate change in Central Asia is already noticeable via glacier melting in the higher elevations. During the twentieth century, the glacier area of the Tian Shan and Pamir-Alai decreased by 25–35%, which clearly indicates warming55,56.

Considering the threatened species (CR + EN + VU), the most endangered group is related to extreme habitats such as water bodies, deserts and semi-deserts (Fig. 4b). It is commonly known that these types of habitats are fragile to climate change57,58. In fact the authors observed a serious decline of shallow saline lakes in the upper altitudes and strong pollution in lower rivers and water bodies in the lowlands. In addition, the share of threatened species in the phytogeographical groups to some extent highlights the effect of climate change, as the highest proportion of threatened taxa has its origin in Central Asia – a much colder and more temperate region than the Irano-Turanian or Mediterranean (Fig. S4). Plants adapted to colder environments reveal a stronger withdrawal tendency than those from warmer climates (e.g. Saharo-Sindian). Interestingly, the pluriregional and cosmopolitan taxa take advantage in the group of extinct taxa when its share is considered – examples are Crassula aquatica or Poa infirma that have a wide range, but in Tajikistan occur in single locations. However, as the number of species is accounted for, the most numerous group is clearly the Irano-Turanian that reflects the rarity of the number of taxa that are endemic to Tajikistan and harbored by distinct and threatened habitats41.

More attractive plants and spring bloomers with a shorter flowering period face a higher risk of extinction

As was expected, species with alluring, beautiful flowers are at higher risk of extinction. The Tajik tradition is to harvest beautiful flowers from the wild and sell them along roads or at markets, and also cultivate plants in their home gardens. This love for nature and beauty unfortunately poses a higher threat to the local flora. The peak of the bulb trade is still a long way behind (e.g. tulips), however there is still an intensive harvest from the wild or simple smuggling of bulb plants, putting many of them at a high risk of extinction (e.g. Eremurus albertii, E. korovinii, E. pubescens, Fritillaria eduardii). These kind of threats are known as the most important risk factors for ornamental plants that are contributing to their decline59,60.

The early blooming plants in Tajikistan are relatively more threatened than the other groups of taxa. This pattern is not so evident, however considering the extinct and vulnerable taxa we can find the shift towards the beginning of the vegetation season. There are few available data on the extinction risk relation to the flowering functional traits based in the whole flora analysis. In the US, a comparison of common and rare taxa showed that an earlier and longer blooming was typical for common taxa61. The same result was found for Finland’s red-listed taxa – with the late bloomers more threatened62. This is contrary to our findings in respect of blooming period, however fully in accordance when considering flower duration. Probably the differences are due to the considerably distinct traditional harvest of early spring flowers in Tajikistan, if compared to the controlled situation – regulated by strict law – in the US and Finland. It can be also related to very variable altitudinal gradient across Tajikistan, whose total denivelation reaches more than 7,000 m a.s.l. Such a topography strongly influences the seasonal variation of the vegetation. The long-lasting spring and related flower harvest begins in February in south-western parts of the country and ends in early July in eastern plateaus of the high Pamir Mountains, impacting a lot of species across an extensive area. An explanation of a lower threat level of long flowering plants still requires more detailed study and would probably have to involve a range of correlated factors such as human impact on short blooming geophytes, plant-pollinator interactions and investment in sexual reproduction63.

Useful plants are less threatened than those neglected in the human economy

Local people in Tajikistan commonly harvest a great number of native plants for different purposes. Many people rely on traditional medicinal plants to prevent and cure health disorders64. Despite the fact that harvesting of useful plants can cause a considerable threat to the flora65, in Tajikistan the usage of medicinal and food plants still seems to be traditional and sustainable, without having a strong influence on the local flora. Probably it is also due to the harsh mountainous relief of the country, with many unavailable and inaccessible lands where no harvest is possible. Another reason that the species used in traditional medicine and the local cuisine are less threatened may be the overrunning effect of other threats (land development, urbanisation, climate change), if compared to other regions. However, the rapid changes in the Tajik economy, infrastructure and population may have deteriorating effects on that sustainable balance.

The need for improving plant diversity conservation in Tajikistan

In the Pamir-Alai, large protected areas have been established in recent decades that cover ca. 22% of the country’s territory37; however, only a few are devoted particularly to floristic diversity conservation. Additionally, a number of programmes and strategies have been developed to enhance biodiversity conservation and management of protected areas, although in practice they are insufficiently managed because governmental institutions are not able to monitor and manage all the valuable plant populations and vegetation types. The compilation of a comprehensive endangered species list will hopefully improve this situation. Raising the effectiveness of conservation in Pamir-Alai needs urgent action plans with the establishment of specific priorities for the hotspots of plant diversity. The identification of micro-hotspots (currently under preparation by the authors) within the global hotspot of the Mountains of Central Asia is necessary, particularly for the most threatened ecosystems such as forests and grasslands.

The need for a stronger national administration must also be emphasised to deal with biodiversity conservation, which must involve the provision of financial support by international organisations. At a national level, the system of nature conservation should be improved so as to take better account of centres of endemism, improving the connectivity of the ecological network and enhancing the adaptive capacity of the most sensitive areas by ensuring a balance between traditional management practices and the economic growth of local economies. All these aforementioned points would not be achievable without a thorough inventory of current species distribution, analyses of their population sizes and phenology changes. This knowledge is an indispensable but still neglected step in conservation actions in Tajikistan.

Source: Ecology - nature.com