Study site

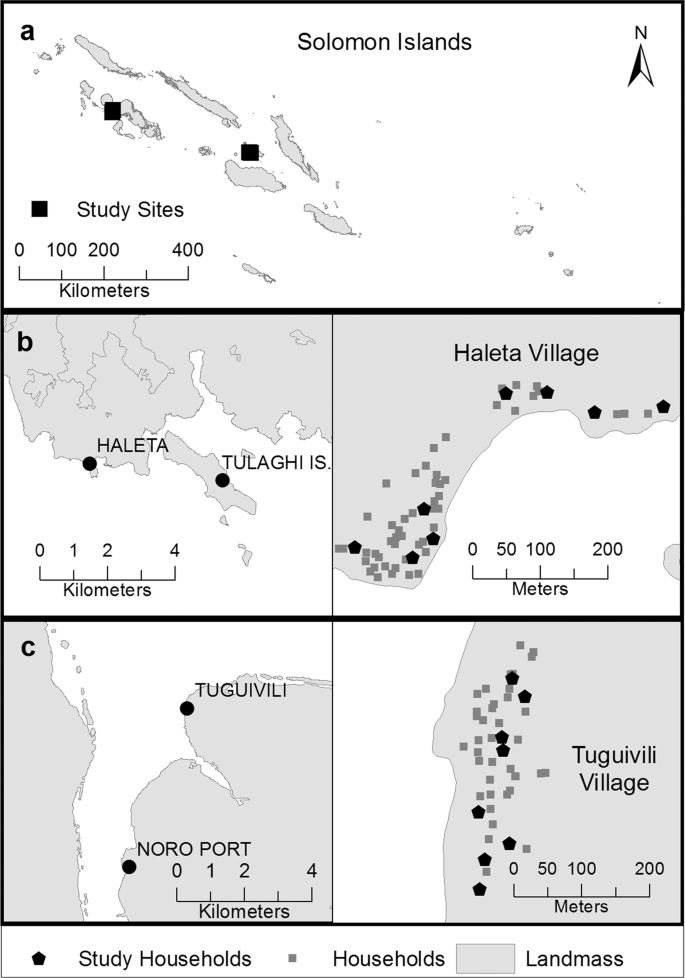

The study was conducted in two typical Solomon Island coastal villages (Haleta and Tuguivili; Fig. 6). Haleta village (population 366 people) is located on Ngella Sule Island in Central Province (9°5′56″ S, 160°6′56″ E). Central Province had an Annual Parasite Incidence (API) of 280 cases per 1,000 persons during 201531. The average human biting rate of An. farauti was 15 bites per person per night (b/p/n) during 2011–201421 Tuguivili village (population 167 people) is on New Georgia Island in Western Province (8°11′49″ S, 157°12′54″ E). Western Province had an API of 30 cases per 1,000 persons during 201531. The human biting rate of An. farauti was 3 b/p/n during 2015–201713. The mean daily coastal temperature for the Solomon Islands ranges between 24 °C and 30 °C with a mean of 27 °C and rainfall between 3000–5000 mm32. Anopheles farauti is the dominant malaria vector in the study villages (and the Solomon Islands as documented in previous studies33).

Map of (a) the Solomon Islands showing (b) location of Haleta village on Nggela Sule Island in Central Province (9°5′56″S, 160°6′56″E) on the right and detailed map of the positions of all households and study housholds on the left and (c) location of Tuguivili village on New Georgia Island in Western Province (8°11′49″S, 157°12′54″ E) on the left with the locations of the all households and study households on the right.

Greater than 80% of the Solomon Island population lives in rural villages. The villages are generally small, averaging 68 residents in 12.4 households. The economy is largely non-monetary with 96% of households practicing subsistence farming with 60% also fishing22. Annual household income in 2013 from selling crops, handicrafts and fish was USD 968 (SBD8011)34. More than 98% of Solomon Island residents are Christians and more than 95% are Melanesian22. Houses in the Solomon Islands are predominantly constructed on stilts with timber frames and timber or leaf-thatched walls, and with roofs of iron sheet or leaf-thatch. Five percent of rural households have electricity and fewer than 1% have television35. The houses have large open eaves and are homogenous in size with 2–3 bedrooms.

Interviews and movement diaries

The lead author (EJMP) conducted the recruitment and enrolment process after permission was obtained from the village chief to conduct research activities within the village. The village was divided into geographic zones, and households meeting the inclusion criteria were selected from each zone (see Fig. 6). The inclusion criteria included household heads having basic literacy, all household members being permanent residents of the study village, and being willing to provide informed consent. Households meeting the inclusion criteria were selected from each village zone.

A total of 86 people were enrolled from 16 households distributed across both villages (Fig. 6). The location of each resident was recorded for 14 days during July 2017. The demographic information of each household was captured with an initial questionnaire that included: number of household occupants, their age, gender and use of LLINs (number/household).

The location of each resident was recorded by the household heads using daily movement diaries for the 14-day period. All household heads received training in the use of the diaries but were not compensated for recording human movement data. Movement diary entries were recorded as short answers in English, the language of instruction in the Solomon Islands. Prior to the start of the study, data collection and recording were trialled for 2 days under the supervision of the lead author and translator to ensure comprehension of the data recording instructions and to ensure accurate recording of data. During the study, the lead author and the translator lived in the study villages and visited households in the evening to answer questions and to check progress including daily inspections of the movement diaries to ensure complete data capture for all recording periods for all household members. The informant recorded his/her movements and approximately 4 other household residents, using both direct observations and reported recall. The validity of diary entries was confirmed by spot checks of diary entries recorded by the informant against independent observations of residents’ locations by the senior author. The lead author and translator were fluent in Solomon Pijin, the lingua-franca used for discussions, clarifications and training.

During the day (06:00–18:00 h), data were recorded in 3 blocks of time, each of 4 h duration. During the evening (18:00–00:00 h), data were recorded hourly. A single block of time was recorded for the night (00:00 to 06:00) when limited people movement occurred. For each time period, the household head observed the location of the household members. Household heads acting as informants were provided synchronised watches set to chime hourly during movement recording periods to remind the household head to complete the diary every hour. The predominant location of each participant was recorded as short open text answers which were subsequently categorised into 4 main broad geographic areas (“Inside House”, “Peri-domestic area”, “Village” and “Beyond Village”, see Table 1). Data entries that could have multiple interpretations were clarified in consultation between informants and study investigators.

Statistical analysis

The age distribution of participants was described and compared with the national baseline average using a chi-squared contingency table (chisq. test). Baseline population data was accessed from projected figures for 2017 based on the 2009 census data22.

Generalised linear models (GLMs) with Gaussian distribution were used to analyse differences in: 1. the temporal location of participants compared between villages; 2. the number of nights that participants spend away from their home village by gender and village;3. the age of participants who travelled compared with the age of all participants; 4. the location of all participants across different times of the day and into the evening (06:00–22:00 h); 5. the location of all participants across different hours of the evening (18:00–00:00 h), 6. the location of participants between weekend and weekday days; and 7. the participants locations inside the house between age groups throughout the evening (18:00–00:00 h). The significance of the interaction between location of the participants and time of the day was analysed using a Chi-square test (anova) that compared the fit of two nested poisson GLM models. This statistical method was chosen because both the factors of location and time of the day were categorical. The eventual sleeping location and the usage of LLIN compared by age group used a chi-squared contingency table (chisq. test).

Quantifying human-vector interactions

Prior to conducting the human movement surveys, the biting behaviour of the local An. farauti population was quantified and published21. The proportion of human contact with mosquito bites occurring indoors (πi) was calculated by weighting the mean indoor and outdoor biting rate of An. farauti throughout the night by the proportion of humans indoors and outdoors at each time period (indoors being humans inside the houses) and outdoors being humans in the peri-domestic area to match with the mosquito data collected “inside” and “outside” of houses): ({pi }_{i}=sum [{I}_{t}{S}_{t}]/sum [{O}_{t}(1-{S}_{t})]+{I}_{t}{S}_{t}); where S = the proportion of humans indoors, I = the total number of mosquitoes caught indoors, O = the total number of mosquitoes caught outdoors [see10 for more detail].

Study limitations

This study had several limitations. This was a small study documenting the locations of 86 people from 16 households in two villages across a single 14-day period. Both villages were ‘typical’ rural villages in a ‘typical period of village life’ where people live in family groups on their customary land and engaged in the rural subsistence economy (96% of the 80% rural population of the Solomon Islands practices subsistence agriculture22). However, the study may have been improved by monitoring the movements of a greater number of households in villages across more provinces. The single 14-day period study period did not allow data collection from different periods of the year, seasons or during social/cultural events. However, the lack of distinct and/or extended wet and dry seasons in the Solomon Islands coupled with the near universal, practice of subsistence farming results in rural village populations having very regular and predictable daily/weekly activity patterns (e.g, tending gardens, selling excess produce at local markets and/or fishing). Almost everybody returns to their village each night and engages with their extended family who live together in the village. Extending the study to include a period of enhanced social movement, for example at Christmas or another religious or cultural event, when former residents return to their ‘home’ village, would have provided information about people movements in ‘non-typical’ periods.

The movement data was composed of both direct visual observations and self-reported recall. Self-reported recall may introduce social desirability bias where respondents report locations that they think are ‘correct’ for the purpose of the study. For example, self-reported use of mosquito bednets is often over-reported (as they are likely to have been in this study). However, during the evening period when most An. farauti bites occur, most people were recorded in directly observable locations. As there is no obvious ‘correct’ answer for locations of individuals, social desirability bias would be minimal. This study did not incorporate cell phone generated data which could have provided information on destinations of village residents moving longer distance. However, as the study focus was on detailing at a very fine scale human locations within villages, cell phones would not have provided detailed information on locations of humans within houses or have distinguished locations within the peri-domestic area. Future research should consider these limitations when designing additional studies.

Ethical approval and informed consent

Ethics approval for this study was provided by the Solomon Islands Health Research and Ethics Review Board (No. HRE046/16) and the James Cook University Research Ethics Committee (No. H6840). All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of these research boards, and as stipulated in the approvals. Each participant completed a written informed consent form before participating in the surveys, noting that consent for minors and children was provided by the household head. The village chief gave permission for work in the village and also provided permission for each selected household to be involved.

Source: Ecology - nature.com