A coupled Hg-C cycle model

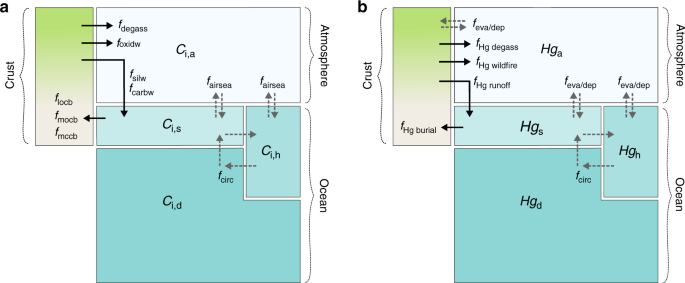

Figure 2 shows the biogeochemical box model developed here. The full model derivation follows in the ‘Methods’ section. The model combines a multi-box sediment–ocean–atmosphere carbon-alkalinity cycle (based on previous work35,36,37), with the global mercury cycle38,39. The ocean is split into ‘surface’, ‘high-latitude’ and ‘deep’ boxes. It considers ocean circulation and carbonate speciation, and contains a simplified organic carbon cycle in which burial rates are prescribed. As well as computing the global C and Hg cycles it also computes δ13C of all C reservoirs and δ202Hg of the ocean reservoirs. A full atmosphere–ocean model of δ202Hg would require dynamic biosphere reservoirs, which would greatly increase model complexity. We therefore simplify the system to a mixing model for marine δ202Hg, in which atmospheric and riverine inputs have different isotopic signatures. The atmosphere is assumed to have (delta ^{202}{mathrm{Hg}}_{{mathrm{atm}}} = – 1) ‰, and riverine input is assumed to have (delta ^{202}{mathrm{Hg}}_{{mathrm{runoff}}} = – 3) ‰, following ref. 40.

Concentrations of modelled species are tracked in boxes representing the atmosphere (a), surface ocean (s), high-latitude ocean (h) and deep ocean (d). Exchange between boxes via air–sea exchange, circulation and mixing, or evasion and deposition are shown as dashed arrows. Biogeochemical fluxes between the hydrosphere and continents/sediments are shown as solid arrows. See text, ‘Methods’ and Supplementary Information for full details of fluxes. a C cycle. b Mercury cycle.

The model is set up for the late Permian by reducing the solar constant to that of 250 Ma, and increasing the background tectonic CO2 degassing rate to 1.5 times the present day (D = 1.5), in line with estimates for the Late Permian41. To obtain the observed pre-event ocean–atmosphere δ13C composition of ~3.5‰, we set the rate of land-derived organic carbon burial to 20% higher than present day, and adjust the composition of the weathered carbonate reservoir to 3‰. This is consistent with high terrestrial productivity and C burial in the Permian (e.g., coal forests and mires) and rapid recycling of more recently buried and 13C-enriched carbonate material.

In the following paragraphs, we test two model end-member scenarios: (I) the release of volcanic and thermogenic Hg and C from Siberian Traps activity alone, and (II) with the additional release of Hg and C as a consequence of the collapse of the terrestrial ecosystems.

Volcanic and thermogenic degassing

We first model the release of volcanic/volcanogenic Hg and C from the Siberian Traps. Existing radioisotope data show that the extinction, the negative δ13C excursion and Hg spike might have all occurred during the intrusive phase of the Siberian Traps20,34,42. It is suggested that the emplacement of large sills caused the combustion or thermal decomposition of organic-rich sediments with the consequent release of thermogenic volatiles, such as C and Hg20,22. It has been proposed that over a ~400 Kyrs intrusive phase the Siberian Traps emitted ~7600–13,000 Mg yr−1 of volcanic Hg, which included both magmatic and coal-derived Hg20,22,23. Relating this Hg release to the background volcanic source is not straightforward because estimates of the background source vary, but taking the most likely present day range25 (~90–360 Mg yr−1), and further constraining this by taking into account the need to balance overall sedimentary burial of Hg (~190 Mg yr−1), and the overall ~50% increase in tectonic degassing in the late Palaeozoic relative to today43, we arrive at a best guess for the background late Permian Hg flux of ~300 Mg yr−1. This means that the Siberian Traps eruption increased the geogenic Hg input by a factor of ~25–43 over ~400 Kyrs.

To test this scenario, we model Siberian Traps intrusion by increasing the volcanic Hg source by 25–43-fold for 450 Kyrs, while also increasing the CO2 source in line with estimates44,45 for Siberian Traps degassing based on magma volumes and sediment intrusion (by 4-8 × 1012 moles/year). The CO2 released by contact metamorphism at the PTME is assumed to have an average δ13C composition of −25‰44. Specifically, the input functions are:

$$f_{CO_{2input}} = , left[ { – 253 – 251.99 – 251.98 – 251.56 – 251.55 – 251} right], big[ {0,0,CO_{2ramp},CO_{2ramp},0,0} big]$$

$$F_{Hg_{input}} = , left[ { – 253 – 251.99 – 251.98 – 251.56 – 251.55 – 251} right], big[ {1,1,Hg_{ramp},Hg_{ramp},1,1} big]$$

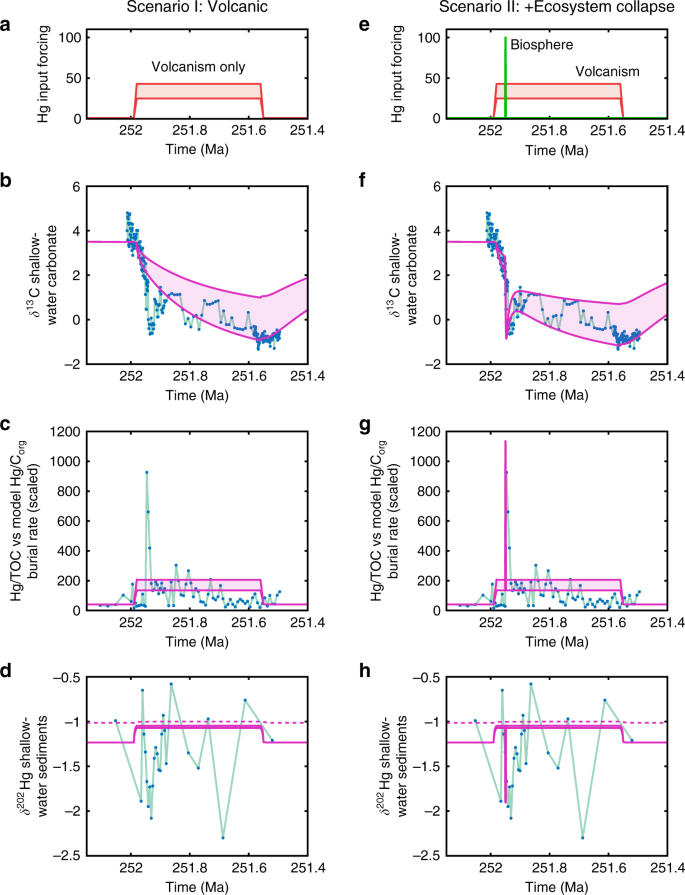

Here the first vector is time in millions of years and the second is the flux alteration at that time. Here (CO_{2ramp}) is the additional CO2 release in mol yr−1, and (Hg_{ramp}) is the relative Hg degassing rate increase. For the duration of these pulses, the thermohaline circulation is also assumed to collapse due to warming and freshwater input46. We reduce the circulation term to 1 Sv over this period, which allows more rapid change in the model surface ocean C isotopes and Hg loading. This is a large reduction, and also reflects the simple structure of the model in which the entire low-latitude surface ocean is represented by a single box, and so is well-mixed. Figure 3a–d shows that this magnitude and timing of release of C and Hg is capable of driving the longer-term decline in carbonate δ13C, and the coeval long-term approximately two- to four-fold enrichment in shallow sediment Hg/TOC that is observed in Meishan. However, the model scenario does not capture the spike in Hg concentration, or nadir in δ13C (EP. I30 in Fig. 1) that are coincident with the final stage of the terrestrial extinction. It also does not produce any substantial change in marine δ202Hg isotopes (Fig. 1d), because the primary Hg source to the ocean is the atmosphere for the full model run.

a–d Volcanic C and Hg source only (thermogenic plus magmatic). e–h With addition of ‘vegetation loss′ Hg source and corresponding increase in organic carbon oxidation. C-isotope, Hg/TOC and δ202Hg data from ‘Meishan GSSP’ section20,23. In both columns, top panel (a, e) shows input forcing in terms of relative rate of Hg input, next panel (b, f) shows δ13C of new shallow ocean carbonate, third panel (c, g) shows Hg/TOC data versus the model molar Hg/Corg burial rate, which has been scaled to match the background as the model does not calculate weights. Final panel (d, h) shows model δ202Hg against data, where solid line is shallow water (box s) and dashed line is deep water (box d) Blue dots = published data; Red and green lines = model Hg fluxes; Pink lines = model output.

Within the model, we have also explored a scenario wherein the large Hg pulse represents a further rapid pulse of LIP volcanism. We have attempted this scenario in Supplementary Note 1 (Scenario I–2), where a 1 Kyr volcanic pulse is assumed to raise the Hg and C input rates by a further factor of 5. While the Hg/TOC can indeed be explained by an additional short-lived pulse of Hg, we require the total release rate of Hg to be ~200 times greater than background levels, and even then, this scenario fails to reproduce any of the Hg isotope signature or the nadir in carbonate δ13C (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Terrestrial ecosystem collapse

For scenario II, we explore the additional effects of a geologically rapid (~1 Kyr) pulse of Hg and C as the result of the collapse of terrestrial ecosystems at the PTME. The magnitude of this Hg flux is again difficult to quantify precisely, and we explore an increase of 100-fold over background conditions. This level of increase represents the magnitude required to drive the sedimentary Hg signal that we observe, and is compatible with the available terrestrial biosphere Hg reservoir: total soil Hg is estimated to be on the order of ~106 Mg Hg when considering a soil depth of ~15 cm47. So, our model Hg delivery flux would require decimetre-scale soil organic matter oxidation over 1000 years, coincident with the PTME and the sharp EP. I negative δ13C shift11. The Hg pulse is delivered directly to the low-latitude surface ocean via runoff in the model, and is accompanied by a pulse of ‘soil oxidation’ C which we assume raises the global rate of oxidative weathering by a factor of 30—a number chosen to have the observed level of impact on the C-isotope record while being compatible with the Hg input change. We also assume a cessation of terrestrial organic C burial. Terrestrial Hg deposition and erosion is not altered during the pulse as the fluxes are minor by comparison. The new model functions applied in addition to the longer-term inputs of scenario I are:

$$F_{Cburial} = , left[ { – 253 – 251.951 – 251.950 – 251.949 – 251.948 – 251} right], big[ {1,1,C_{ramp},C_{ramp},1,1} big]$$

$$F_{oxidw} = , left[ { – 253 – 251.951 – 251.950 – 251.949 – 251.948 – 251} right], big[ {1,1,O_{ramp},O_{ramp},1,1} big]$$

$$F_{runoff} = , left[ { – 253 – 251.951 – 251.950 – 251.949 – 251.948 – 251} right], big[ {1,1,Hg_{bio},Hg_{bio},1,1} big]$$

Here, the first vector is time in millions of years, and the second shows flux multipliers at these times. (C_{ramp},O_{ramp}) and (Hg_{bio}) denote the relative rate of land organic C burial, oxidative weathering and Hg runoff, respectively, and are set at 0, 30 and 100, respectively, for the duration of the 1-kyr pulse.

This ‘biosphere’ pulse causes a short-term large concentration spike in the shallow marine Hg reservoir and its sediments, which is superimposed on the volcanically driven changes (Fig. 3e–h). The Hg spike is far larger than would be expected from simply increasing the volcanic source by the same amount because the biospheric Hg is delivered directly to the surface ocean and sedimentation occurs mostly on the shelf. With the inclusion of terrestrial C oxidation and cessation of terrestrial carbon burial, the model also replicates the transient shift to more negative δ13C values recorded at the marine extinction interval (EP. I30,31 in Fig. 1): Terrestrial C oxidation is a source of isotopically light C48. The model now also shows a sharp negative δ202Hg shift in the shallow ocean box, which is triggered by increased Hg riverine input, but shows no change in the deeper ocean, where the source of Hg remains predominantly atmospheric. This also compares well with existing records (Fig. 3). At Meishan, which was located in the margins of the Yangtze carbonate platform, the Hg and Hg/TOC spike is coincident with more negative δ202Hg values (Fig. 1), while in the deeper water sections of south China the values are more positive20,23.

Hence, oxidation of terrestrial biomass is a compelling scenario to explain the palaeontological, sedimentological and geochemical data. There is clear observational evidence for the collapse of the terrestrial ecosystems and cessation of terrestrial C burial, stratigraphic evidence supporting the sequence and timing of the events (onset of the δ13C shift—collapse of the terrestrial ecosystem—Hg and C spike), sufficient quantity of Hg available, consistency with the isotopic evidence for changing Hg sources, and consistency with the δ13C records.

Massive terrestrial biomass oxidation during the PTME

Using our coupled C–Hg biogeochemical model, we show that the massive collapse of terrestrial ecosystems and oxidation of terrestrial biomass during the Permian–Triassic extinction had a huge impact on global Hg and C biogeochemistry. Hg stored in the terrestrial reservoirs was rapidly released as a consequence of the loss of terrestrial biomass and increased soil erosion9,14. This mechanism is the best explanation for the sharp increased loading of Hg into both terrestrial and marine water bodies and the negative shift in δ202Hg in coincidence with the marine mass extinction. Contemporaneously, increased soil carbon oxidation introduced large quantities of isotopically light C, accounting for the sharp negative δ13C anomaly registered in the sedimentary record (EP. I30). In the model, the emission of Hg and C from magma and heating of sedimentary organic matter during the intrusive phase of the Siberian Traps LIP emplacement can account for the smaller, two- to fourfold increase of Hg concentrations with respect to background levels, and the relatively longer negative δ13C trend that is recorded by both carbonates and organic matter, in marine and terrestrial settings.

A new scenario emerges for the PTME that links the collapse of ecosystems on land to the global geochemical changes recorded at the marine extinction interval. The disruption of terrestrial environments started during the initial phases of the Siberian Traps emplacement likely due to the release of volcanic gases as CO2, SO2 and halogens, which could have triggered acid rain, ozone depletion, volcanic darkness, rapid cooling and subsequent global warming8,49. At the culmination of the terrestrial disturbance interval, when the ecosystems totally collapsed, large amounts of 13C-depleted C and Hg deriving from a massive oxidation of terrestrial biomass were transported into aqueous habitats causing a steep decline in sedimentary δ13C (carbonates and organic matter), a sedimentary Hg concentrations spike and a shift in δ202Hg (Fig. 3). At this level, the marine mass extinction started. This, according to the existing chronostratigraphic framework, happened ∼60 Kyrs after the onset of the carbon-isotope perturbation and of the terrestrial ecological disturbances14 (Fig. 1).

The biogeochemical cycle of Hg is intimately linked to the cycle of organic matter and its constituting elements, such as C, N, S and P50. Hence, besides Hg and C, other organically-bound species would have been transferred from the terrestrial reservoirs into the marine system in large quantities at EP. I (Fig. 1). Addition of these species, particularly the nutrients P and N, are easily capable of driving ecosystem turnover, anoxia and eutrophication, and it is likely that this terrestrial input contributed to the marine extinction9,11. Our model does not include these additional cycles, but other models have shown that a relatively small increase in marine P delivery (2–3-fold) has the potential to drive marine anoxia or euxinia51,52. The scale of the terrestrial ecosystem collapse at the PTME could explain the severity of the biotic crisis at the Permian–Triassic boundary at all trophic levels, and should be a key consideration for future research. For other events, the Hg records are not so consistent nor as detailed as for the PTME. However, it is very likely that future research on other intervals could show the same Hg and C patterns as for the PTME.

Source: Ecology - nature.com